You could say that she died at the hands of the white man too

The posse didn’t wait to start shooting as they drove their horses down into the wash where the Indians slept in their camp. The reward had been promised whether they were brought in dead or alive. It was easier to kill them all.

On a cold February day in the Nevada hinterlands, a battle raged for three hours, pitting 13 Indians with few guns and little ammunition against 19 well-armed vigilantes. The women defended themselves and their children with spears and arrows. The little children threw rocks at the invaders.

One of the whites was killed as he advanced when a girl held up her skirts and flashed her genitals, smiling and moving forward in a weaving dance. As the white man stared in astonishment, she dropped down and her brother shot him with the one bullet left in his gun.

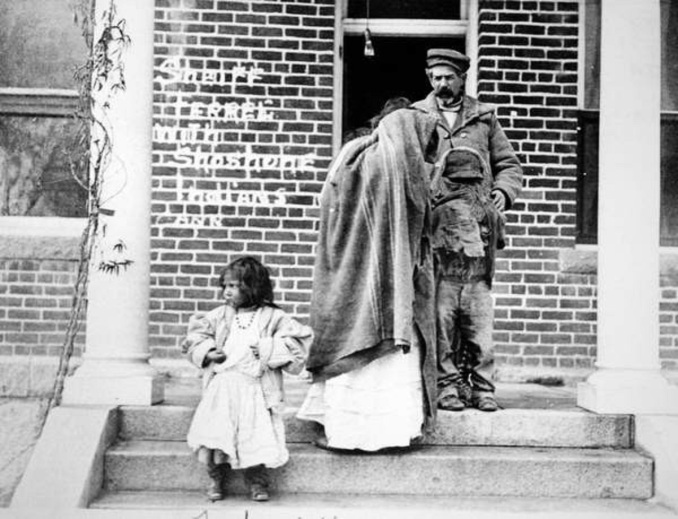

The youngest baby was in a cradleboard on her mother’s back when her 19-year-old mother was shot and killed. Her head fell back into the snowy mud. The marauders heard the baby crying and retrieved her along with three other children who had run into the sagebrush.

That baby grew up to be Mary Jo Estep, the last surviving Indian of the last Indian massacre in 1911, a woman I would meet many years later.

She was one of four children who survived the massacre, but the other three died the following year of tuberculosis. Mary Jo was about 18 months old when the posse ambushed the remnants of her tribe. Her grandfather, “Shoshone Mike,” had led the band across 300 miles of western desert in northern Nevada and California after refusing to go to a reservation.

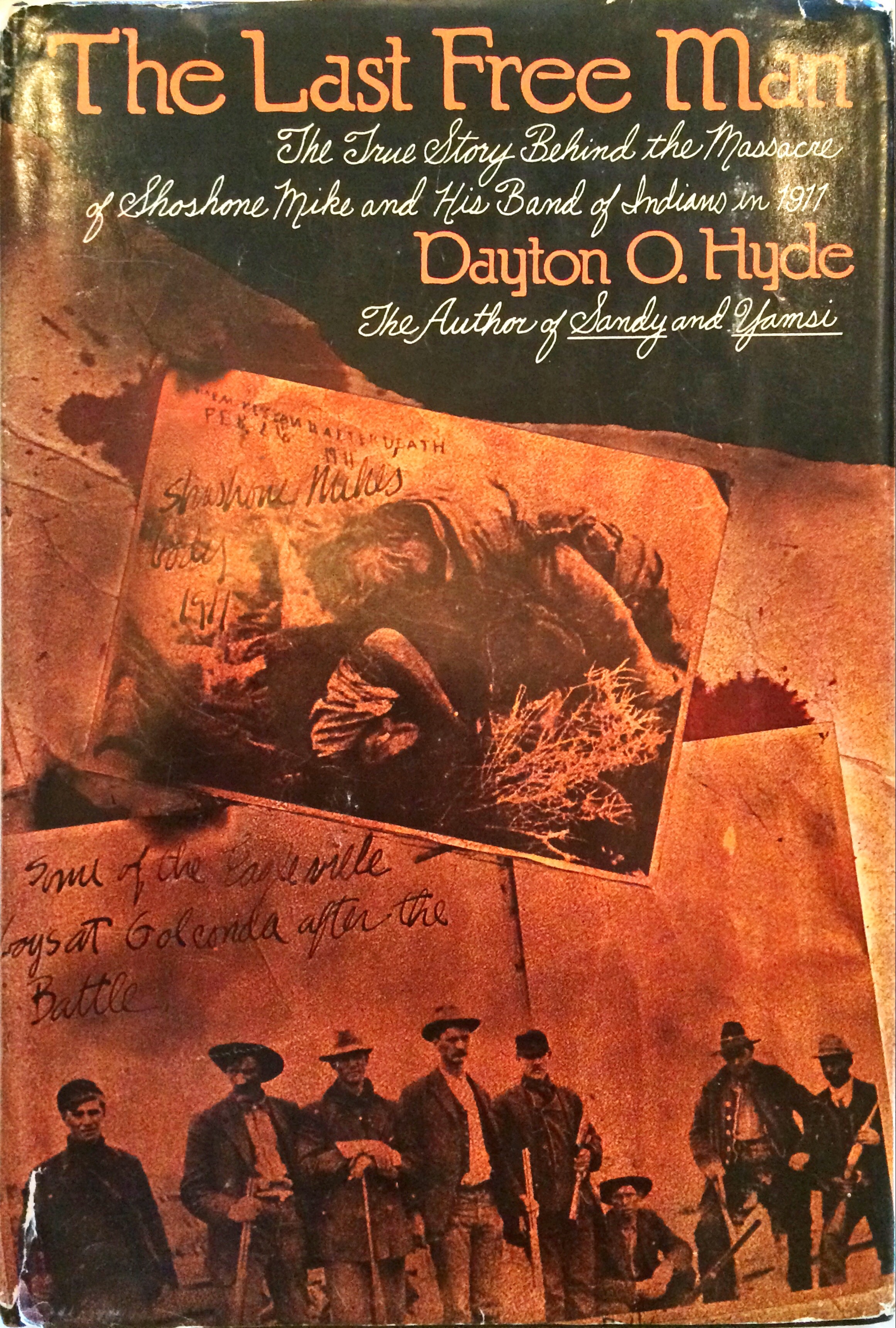

Mary Jo knew little of this and did not remember it. When, in 1973, the Oregon writer Dayton O. Hyde wrote a book about her grandfather and the massacre, he speculated that the children might still be living. He learned of Mary Jo and then agonized about how to approach her and tell her the story of the massacre.

In 1911 Indians had no rights and were not considered human. White men could get away with killing Indians with impunity. It was easy to blame crimes on Indians, and that is what happened to Shoshone Mike. A cattle rustling gang whose leader was the son of a prominent judge blamed their crimes on Mike. A vigilante group formed with eyes on the reward money. Federal marshals also were after Mike and posses began roaming the desert in northern Nevada looking for him.

Mike and his extended family evaded the posses for a year. But the winter of 1911 was the worst in a long time and, starving and tired, they were forced to camp in an unprotected spot where they were discovered.

The surviving children were taken to the jail in the nearest town and eventually moved to an Indian school. The murdered Indians’ bodies were never properly buried.

Until Hyde wrote the book it was still said that Shoshone Mike had committed crimes and the killing of his family was justified. Mike’s crime was that he wanted to live the nomadic life he had grown up with, camping every winter for 30 years on Rock Creek in southern Idaho and then moving to higher country for the summer season. The white man’s fences, sheep and cattle, mining waste, and development made his family’s lifestyle more and more difficult.

Hyde had been obsessed with the story of Shoshone Mike and his research included interviews with people who still remembered the massacre 60 years later. He traveled the route taken by Mike and his family, even collecting remaining bones of the Indians and reburying them.

Writing the book, he set the story straight. Mike and his family were innocent of the crimes whites accused them of. The murderers were never brought to justice; they were hailed as heroes by people in the surrounding towns. Hyde also uncovered evidence that Mike was Bannock, not Shoshone. His wife, Jennie, was Ute.

When she learned the story, Mary Jo’s first reaction was to discount it. “Most of my friends are non-Indians. I was raised in the white world,” she said.

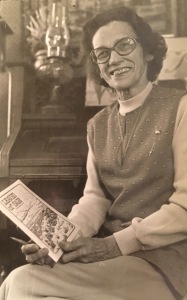

Later she became a local celebrity of sorts in my hometown of Yakima, Washington, giving interviews and speaking to groups who wanted to hear her unique story.

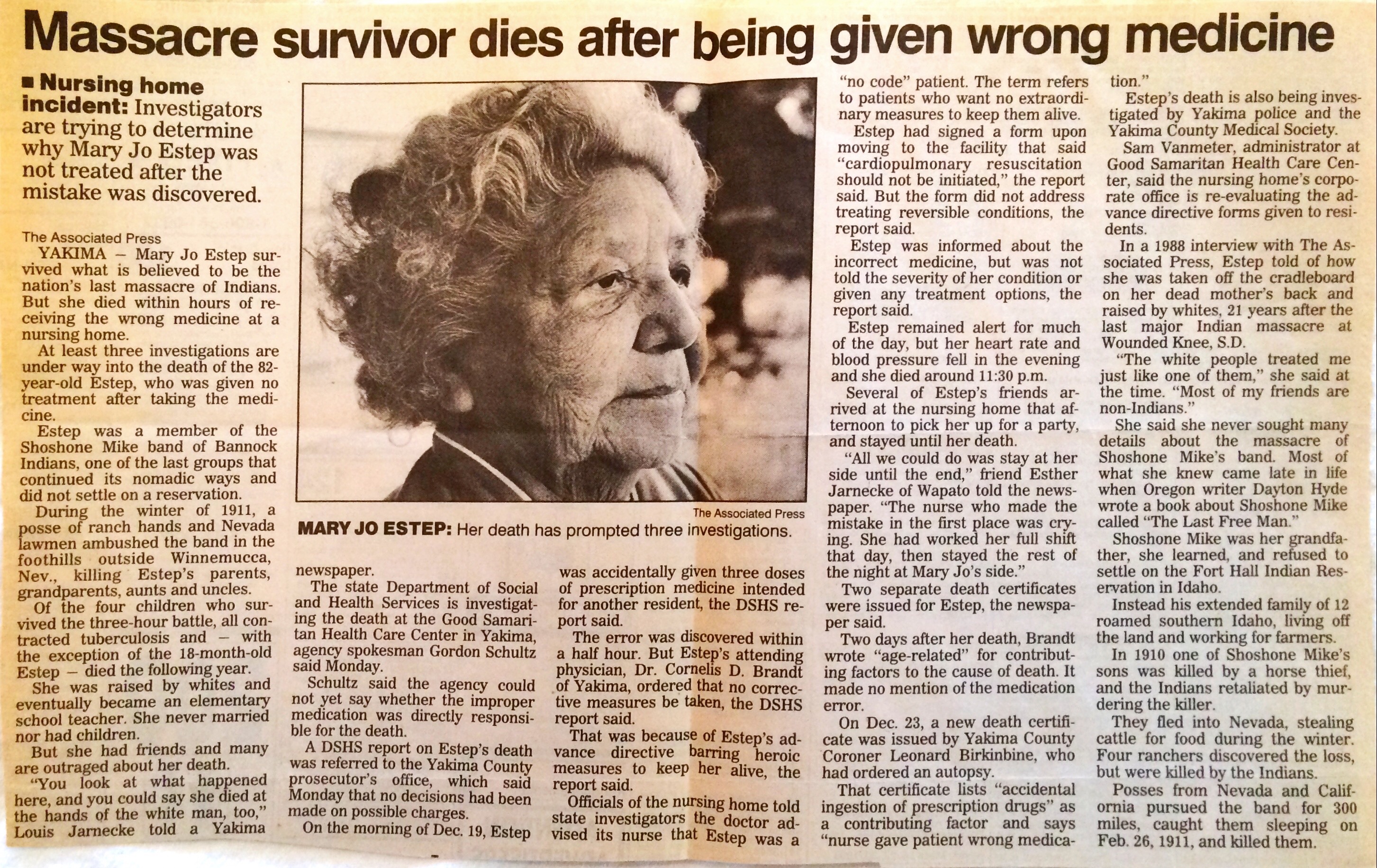

Mary Jo Estep was raised by the family of the Fort Hall Indian reservation superintendent. She graduated from Central Washington College with a degree in music and spent 40 years teaching school before retiring in 1974. At the age of 82 in 1992, Mary Jo died in a nursing home because a nurse had given her the wrong medication and hospital staff determined that her non-resuscitate directive meant that they could not help her. The effects of the overdose could have been easily reversed. She took several hours to die and in that time her friends, who had come to pick her up for a party, surrounded and comforted her, but could not move the doctors to save her life.

“You look at what happened to her, and you could say that she died at the hands of the white man too,” said Louis Jarnecke, one of her friends.

I still have the newspaper article telling of Mary Jo’s death, and the book written about her grandfather, The Last Free Man. What they don’t say is that Mary Jo Estep was a lesbian. She lived with her “long-time companion” Ruth Sweany for more than 50 years on Summitview Avenue in Yakima.

I met Mary Jo and Ruth through my mother who had organized a seniors’ writing group in Yakima. My mom was interested in the history of our part of the world and she encouraged old people to tell and write their stories. She worked for the senior center there and for a time she produced a local TV program in which she interviewed old-timers and recorded their histories. The women told me they were part of a group called “Living Historians,” and laughed saying, “At least we’re still living!”

In 1980, my brother Don and his press, Hard Rain Printing Collective, printed a chapbook that includes the writing of all three: Mary Jo, Ruth, and my mother Florence Martin. Mary Jo’s only piece in the chapbook chronicles an incident from her childhood of an old man who is lost and then found the next day by neighbors. Two of the published entries are by my mother. Ruth Sweany has four; three are poems, but the fourth is a prose piece that describes her life with Mary Jo, particularly when their friend Mabel comes to visit on Fridays. I think the friend must be Mabel George, another writer published in the chapbook.

A photo in the archive Yakima Memory from the Yakima Herald-Republic newspaper shows Mabel George (born January 8, 1899) at the piano, and another entry is titled Mabel George Children’s Songs from 78 records, 1947. So Mabel was a musician and songwriter.

Ruth’s story never mentions Mary Jo, but clearly the “we” in the piece refers to Ruth and Mary Jo as a couple. It’s about the fun they have when their friend Mabel visits. They listen to music (a critique of modern loud disco music follows), they read poetry and plays to each other. They also write and produce plays, calling themselves “The Carload Players.” Ruth writes that they even produced a couple of plays before an audience. This makes me wish their papers had been archived but I can find no evidence that they were saved.

These women rejoiced in each other’s company. Ruth writes: “So our Fridays are always cheerful. Why not? We are doing things we enjoy, in a congenial group. After one of Mabel’s visits the world stops going to the dogs and the sunshine comes out a little brighter.”

Mary Jo died November 19, 1992. Ruth died November 28, nine days later. They were both buried in the Terrace Heights cemetery in Yakima. They chose identical gravestones.

Ruth and Mary Jo carved out their own woman-centered culture in the hostile environment of Eastern Washington before the advent of the modern women’s movement and lesbian pride. Living lightly on the cultural landscape served them well.

http://www.reviewjournal.com/news/shoshone-mike-s-story-endures-after-century

Wow!!!!

I love that story!!!!

You have a very interesting life….. Full of great memories!!

Thanks for sharing!!!!

Love Ana

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Ana! I know. I’ve been carrying this story around in my brain for decades. Nice to be able to share it.

LikeLike

I worked for 3 years in “back-of-beyond” Nevada, most often in the company of Shoshone archeologists and monitors. I heard stories of Shoshone Mike many times from them, albeit from a very different perspective from historical accounts. This is so great to hear yet another untold aspect of that story. History belongs to all of us – “Like amnesiacs in a ward on fire, we must find words or burn.” Thanks again for finding the words, Molly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Barb, that is fascinating! I did do more research on Shoshone Mike and it seems there’s some revision going on lately about the history. Apparently he was set up. I appreciate your comments!

LikeLike

What a wonderful story! Those women and their lives are all fascinating. I would like to learn more about all of them. Thanks so much for sharing this important corner of history. And thanks for writing in such a clear, concise, heart-felt manner. Very enjoyable read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, we now live in the house Mary Jo and Ruth lived in for years. I am interested in learning more about what you know about them and their writings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How wonderful! Email me your contact info. I can send the few things I have. How do you know it was their house? I don’t suppose you found anything Of theirs in it. Tradeswomn@gmail.com

LikeLike