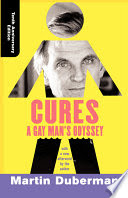

Reading Cures by Martin Duberman was painful. Duberman details his fraught decades of searching for a cure for homosexuality through psychotherapy. The book thankfully ends with self-actualization and the blossoming of the gay liberation movement. But for chapter after chapter Duberman is bludgeoned with pronouncements by homophobic smugly complacent therapists that just made me want to bludgeon them. I know that therapy can be helpful (not conversion therapy!), especially since the gay and feminist movements mounted a successful critique over many years, but I’ve always distrusted the psycho industry. I wrote this essay in the mid-nineties. The theme was polyamory. It’s not a critique of psychotherapy but, reading it again after a couple of decades, my disdain is clear. I felt I’d been harmed more than helped.

Reading Cures by Martin Duberman was painful. Duberman details his fraught decades of searching for a cure for homosexuality through psychotherapy. The book thankfully ends with self-actualization and the blossoming of the gay liberation movement. But for chapter after chapter Duberman is bludgeoned with pronouncements by homophobic smugly complacent therapists that just made me want to bludgeon them. I know that therapy can be helpful (not conversion therapy!), especially since the gay and feminist movements mounted a successful critique over many years, but I’ve always distrusted the psycho industry. I wrote this essay in the mid-nineties. The theme was polyamory. It’s not a critique of psychotherapy but, reading it again after a couple of decades, my disdain is clear. I felt I’d been harmed more than helped.

A Boomer’s View of Nonmonogamy

Like many of my generation of radical feminists who came of age during the 60s, I railed against the institution of marriage and practiced non-monogamy zealously. In that era of free love, opportunities for sex were plentiful. My subset of radical iconoclasts in college hosted organized and not-so-organized orgies, sex parties and porn viewings. Gay sex was acceptable and even avant guarde. In the 60s and early 70s, when I was straight, non-monogamy was easy. I never fell in love with men.

Twenty-some years in the San Francisco lesbian subculture served as an excellent apprenticeship in the world of open relationships. Experience has tempered my early enthusiasm. Today lesbian polyamory—the loving of many women at one time—has for me more associations with community than with lust.

In the mid-70s, after a decade as a practicing heterosexual, the prospect of becoming a lesbian appealed to me for all sorts of reasons besides great sex. Without the constraints of het sex roles and family expectations, I reasoned, we lesbians were free to invent our own culture. Well, theoretically. With parents as our main role models, we tend to draw from the dominant culture. Then there was all that guilt about sex that females of my generation were stuck with. Still, we had more freedom than any previous generation of women to experiment with love and lifestyle. And we did.

Open relationships and casual sex were not unusual among San Francisco dykes I knew in the 1970s. Contrary to currently fashionable revisionist lesbian history which paints 70s lesbian-feminists as self-righteous Puritans, much sex was had by many. Perhaps the dykes partial to penetration were not the same ones who were writing theoretical diatribes, but I can testify we were not lonesome. As with many liberation movements, a whole subset of the lesbian community was committed to experimenting with nontraditional models of loving. Non-monogamy was politically correct.

I was a staunch believer in open relationships in 1977 when I got involved with a lesbian who already had a primary lover and a job that required waking at 4 AM. It took a year of crying jags and bedside bottles of bourbon to shatter my idealism, then two more years of break ups, hot secret rendezvous, and re-negotiations with the other woman to get free.

She: OK, you can have her Friday, but I get her Saturday night.

Me: What a rip! She’s always asleep by nine on Friday.

She: Yeah, well, she can’t stay awake on Saturday either.

At one point, the other woman and I even resorted to sleeping together to get our lover’s attention.

Non-monogamy might work, I decided, if sections of the triangle were exactly equivalent or if relationships were all we had to devote our lives to. But for wage slaves like me with more to do than process relationships, having one lover at a time was the only practical option. Besides, I’d fallen madly in love with a new woman.

Many years of serial monogamy followed. A five-year relationship with a perfectly wonderful woman ended when my commitment to monogamy failed. My lover had made it clear that the relationship would end as soon as I slept with another. She defined the boundaries, but I agreed that the intimacy we felt would not survive non-monogamy. She was the supersensitive type who knew what I was feeling even before I felt it.

She: Something’s going on and I want you to tell me what it is.

Me: Going on? What do you mean by going on? If it stays in my head is it going on then?

The contradiction: I wanted to stay in the relationship, and I didn’t want to hurt my lover. But I developed obsessive attractions to other women and worried constantly about my ability to stay faithful. By then I knew better than to end our relationship by running off with another or lying and I never had an actual affair while we were together. Finally, though, I found the monogamous vow to be one I wasn’t able to live with any longer. Our parting was not without trauma, and healing took time, but my ex is now a dear friend.

Early on I observed that lesbians in my generation talked a lot about long-term monogamy, but few really practiced it. We acknowledged the two-and-a-half-year itch and the five-year itch, at which time it seemed natural to move on to a new love interest. The therapeutic community, watchdogs of lesbian culture and creators of relationship lexicon, did not disapprove as long as you were honest and made sure your lover understood your feelings (Don’t run off without telling her in couples therapy. That’ll be $40). Sometime in the mid-80s, in the wake of AIDS hysteria, therapists decided that we were not working hard enough at our relationships and that divorce was pretty uniformly a bad thing. No doubt lesbians broke up just as frequently thereafter, but our level of guilt rose dramatically.

While our subculture reflected the changes going on in popular culture at large, lesbians knew we were unique. That had become more apparent as we watched the gay men’s and women’s subcultures develop so divergently in the decades following Stonewall. In general, women shunned casual sex and valued emotional intimacy. Picking up a one-night stand was a tougher assignment than finding a gal who wanted to get married. Our interest in the intricacies of personal interaction made us highly evolved players in the realm of relationships. We talked endlessly about sex and love and all of our new discoveries, and we spent thousands on therapy.

In 1982, my lover of two and a half years dumped me, and then my mother died. My intense grief led to an existential epiphany. Suddenly I was hiking down the other side of that mountain of life, where the air is fresh and where the continuity of all our human connections creates a clear vision. Friends, girlfriends, ex-lovers and lovers—my established family—all assumed a much greater level of importance for me. Once they came into my life, I decided, they were permanent lifetime fixtures. Keeping them, maintaining relationships in whatever their changing forms, became my central focus. Instead of putting all my emotional eggs in one primary lover basket, I vowed to distribute them widely.

That web of constructed and nurtured relationships is, for me, polyamory. I love many women, and the boundaries of our relationships are not always clearly defined. Perhaps one problem is the dearth of available descriptive terms. To adequately represent the depth and breadth of our relationships in lesbianland requires many more categories than the two basics: lovers and friends.

Just as I began to feel a tinge of wisdom, an unexpected new pattern emerged in my forties. At the end of 1993, I wrote to my first woman lover:

Age has humbled me, especially in the realm of personal relationships. Remember when we broke up, I vowed I had done with nonmonogamy forever? To my great surprise, I’ve spent the first half of my forties practicing something very like it, though not exactly. Now six years out of a relationship, I’ve always had lovers, but not in succession as lesbians usually do. These non-relationships seem to take place simultaneously and overlap each other. We move apart, then we might come back years or months later. The transitions tend not to be traumatic as they were years ago. We might break up as lovers, but it is always with the expectation of continuing a friendship or reconnecting as casual lovers in the future.

I’ve lived alone for the better part of the last decade rather arbitrarily, for it was never what I would have chosen for myself. I would prefer to live with people, though I’ve never aspired to live in a couple with a lover, which, to my dismay, remains our dominant model. Still the experimenter, I seek to invent new models, but there’s little support for that, at least among dykes in our age group. I do get lonesome for a daily presence in my life, but I don’t miss the “work” of relationships. Actually, I’ve come to believe that if it takes very much work, I’d rather not be in it. Still, I’m halfheartedly seeking Ms. Right, answering personal ads, and asking my friends to fix me up with single women. ….I find that I take affairs of the heart much less seriously than ever before. I’m seldom driven by the sexual obsessions that continually threatened to break up my 5-yr. relationship (is that a function of age or marriage?), and I’m much better at casual sex than ever, which I mostly think is good but sometimes makes me feel terribly jaded. Mostly I stand back and watch my own life with wonder and sometimes surprise (sometimes boredom), anticipating the next chapter.

My specialty became distance. Not emotional distance, though some have argued this point. Rather, loving women who lived great distances away. The first lived in rural New Hampshire. We had been lovers briefly years before when she had lived in California. Our paths crossed again as tradeswomen organizers, and we kept meeting at the same conferences. The flame spontaneously rekindled when we began to work on organizing a national conference in 1988.

Fortunately, our affair coincided with a planned year’s leave from my work. I could stay with her for a month or two, then return home again before domestic strain or lesbian bed death began to set in. We had no expectation that our lover relationship would last forever, and in fact my returning to work in San Francisco was the beginning of the end. We couldn’t see each other often and the physical distance translated into emotional distance. It took another year for us to call it quits as lovers, with the full expectation that we might again become lovers in the future, since that had been our established pattern. Now solid friends, we’ve seen each other through many subsequent relationships. She has acknowledged her own pattern of serial monogamy and now tells lovers up front not to expect long-term commitment.

In the meantime, my sex partners included ex-lovers, old friends and new interests. All my relationships, even fuck buddies, required an emotional component, and I found I became disinterested in sex when the romance died. I allowed myself to be strung along for several years by a babe who maintained another primary relationship (hadn’t I learned this lesson?). I kept my head above water by telling myself I knew how to leave when it got too painful. She was one of those non-verbal types whose distaste for process eclipsed even my own.

Me: I’ve wrestled in my own mind with the other woman thing, the age difference thing, those awful shirts you insist on wearing. I think I’d like to continue seeing you. If we have a relationship, what would it look like for you?

She: Wow, look at the time! I think I have a tennis match. Gotta go.

Relationship discourse was futile, but I felt compelled to try periodically to explain my feelings. For two un-drama queens, we generated our share of dyke drama. Today, as I watch her dramas continue with others, I’m relieved we’re no longer lovers, and glad to call her family.

Overlapping love interests presented unique challenges. I found I needed some time to decompress after one before going on to another, although I didn’t always heed my own advice. At least once I was compelled to see three in one day and more than once I was caught in flagrante delictowith one lover by another. A familiar scenario from my youth was repeated—of waking up in the morning to a head of short dark hair on the pillow next to me whose face might be one of several. Fortunately, I’m a morning person who usually wakes before my lovers, so I had the advantage of a few private moments to get my bearings before murmuring the wrong name. I soon learned to avoid the emotional yo-yo effect of moving too swiftly from one to another by taking some time to myself in between.

When I began an affair with a New Yorker I’d met river rafting, my friends and even casual acquaintances pointed out that long distance love affairs had become my pattern, and what did that mean about my inability to commit? The therapist suggested this “avoidance of intimacy” meant I’d suffered abuse as a child by my father. Repressed memories failed to reveal an explanation, so I decided to relax and enjoy the present.

My dalliance with Ms. New York continued for four years, and while it often left me longing for the kind of daily connection that a local lover provides, I still swoon with fond memories. Our cross-continental meetings every month or two were adventures in a luscious sea of sexual abandon. Always on vacation, we could strip off all our mundane work-a-day worries and have fun. Issues did arise, and were discussed by phone, but didn’t become the focus of our time together.

Our relationship did not fit into any common lesbian-accepted categories. We debated how long an affair can last before it must turn into something else. I contended that, under the right circumstances, it could go on indefinitely, although without living examples, the case was a hard one to argue. Everybody I knew who’d engaged in long-distance affairs had broken up before too long. My lover imagined a different scenario: the relationship just continues to mature, toward greater commitment, toward greater closeness, the goal being a kind of lesbian nirvana–moving in together. I was having trouble visualizing the ultimate emotional goal. My hunch was that the hot sex and passion were directly related to that distance. Could we sustain them if we lived in the same city?

She: The sex will just get better as we get closer.

Me: Do we just get closer and closer until we implode?

The ending? More like an explosion. Our relationship was open, we both dated others, and we’d acknowledged that one of us might get involved with someone else closer to home eventually. It happened to be me. Polyamory, it turned out, wasn’t a model Ms. New York could live with. Now that we’re no longer lovers, we’re trying to figure out how to build and sustain a long-distance friendship without our most compelling element—sex.

For three years now, I’ve remained happily monogamous with a lover who’s newly out. Again, it was she who set the parameters. Our continuing discussion:

She: Sleeping with anyone else is a divorceable offense.

Me: How about only once? How about having sex with someone else at a sex club when your lover is present? How about in a three-way with your lover and someone else?

She: How about getting over it?

Remaining monogamous has been easier for me in my later-forties. Perhaps peri-menopause reduces the quantity of sexual energy, or perhaps there are just fewer temptations. Since my lover and I maintain separate homes and separate busy lives, the time that we do spend with each other is highly valued as is the time we each spend alone.

In retrospect, I’m glad I haven’t lived by a strict definition of the parameters of relationships. The rules have changed according to my life’s circumstances, the preferences of my partner at the time, and the compromises we’ve made to keep us both happy.

We boomers came of age in the 60s, that heady era of principled experimentation, with an ardent belief in our ability to construct a new world. Because the feminist movement–with our enthusiastic participation–did fundamentally change our own lives, many of us retain that idealism. I’m still committed to building relationships based on our own desires and needs rather than traditional patriarchal models. The next generation of dykes will have a fresh perspective and vision.

The lesbian culture we’re building continues to offer a critique of the dominant heterosexual culture, even as our own relationships are influenced by it. As we blur boundaries and redefine relationships, we’re sensitive to the connections we make with each other on all levels. Our freedom and willingness to experiment will result in lots of new models that hets can copy.

I don’t regret any of my relationship experiments–even the painful ones. My only regret is losing contact with friends and former lovers, because I expect them to stay in my life forever in some form—maybe one we have yet to invent.

Great read. 🙂 … and now? … not the therapy thing, but the relationship thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha! Yes, I should report on the last quarter century. I’ve surrendered to the dominant paradigm, not unhappily. I’ve been in a committed monogamous relationship with Holly for nearly ten years. Before that Barb and I were together for 12 years. I continue to maintain friendships with exes. In fact, Holly and I introduced our exes, Barb and Ana, they became a couple and have a special place in our lives. We call them Exes and Besties. I wrote about them on the travel blog travelswithmoho.wordpress.com.

LikeLike