John Dos Passos travels around the zone

Ch. 89 My Mother and Audie Murphy

In her album Flo saved a Report on the Occupation published in Life Magazine authored by John Dos Passos*. In late autumn, 1945, Dos Passos traveled around occupied Germany and wrote about encounters with Germans in cities and in small towns. Here are some passages from his report.

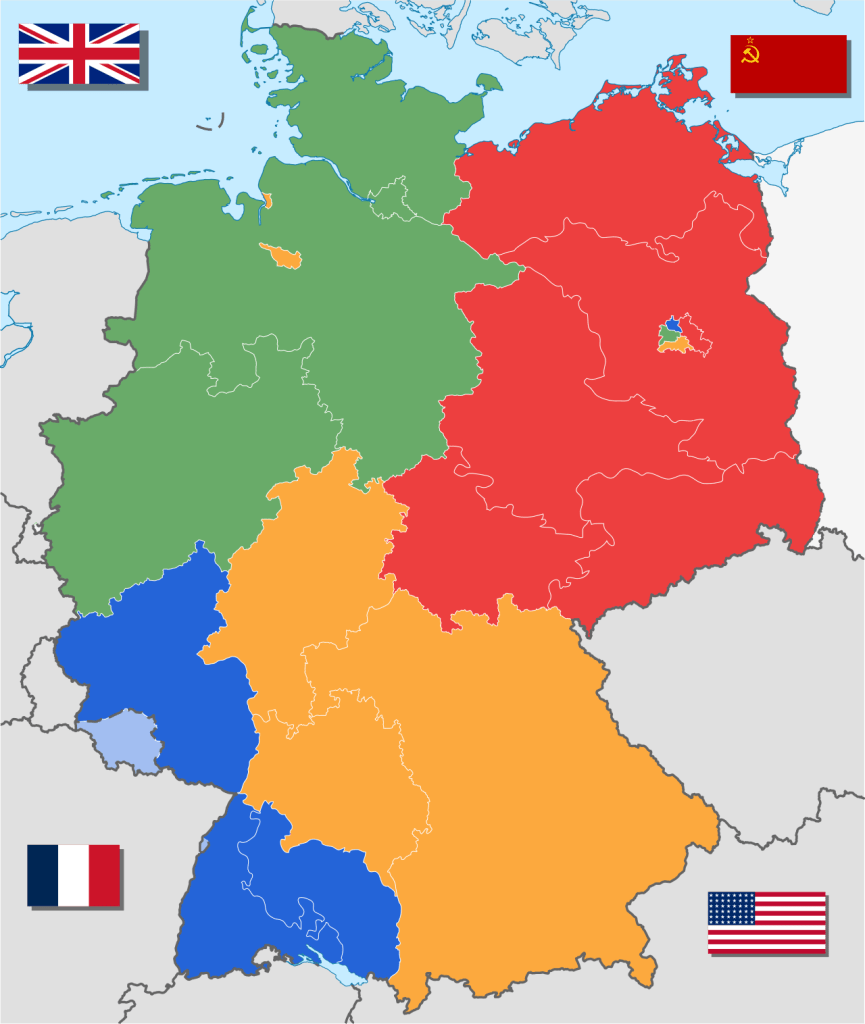

“In the American zone in Germany reconstruction stands still and victors are as glum as vanquished.”

Image: Wikipedia

Dos Passos traveled through “medieval villages out of the backgrounds of Breughel and Hieronymus Bosch.”

“We began to see Hessian peasants in their traditional dress. The women wear their hair pulled off their faces and tied up in stiff little cylindrical topknots on the top of their heads. They wear embroidered blouses and black knee length dresses fluffed out by numerable petticoats. The men wear black smocks and knee breeches over the same heavy knitted stockings the women wear. Some of them have 18th century-looking black felt hats. They have grim nutcracker faces. They slog along beside long wooden carts, drawn by oxen or bulls or cows…. Here and there you even see a wooden plow.”

“In every farmhouse, yard, right under the front windows, you see the steaming manure piles that so intrigued Mark Twain. Long coffin-shaped tanks on wheels are hauling tankage, and human manure out to the fields. Like the Chinese, the Hessians can’t afford to waste a thing.”

One village had a lady burgomaster. She was a fresh-faced young woman with glasses. Unmarried, she had been chief clerk in charge of rationing under the old burgomaster. She had never been a Nazi. We asked if she knew she was the first woman in her country to hold the post of burgomaster. She didn’t seem impressed. “Somebody’s got to be first” she said flatly.

Image: Dogfacesoldier.org

“About the time of the book burnings the people of this town managed to make about 300 volumes disappear. One man walled up his library with a brick wall. All these old pre-Nazi books are ready to go back into circulation.”

As part of the denazification program, all Germans had to fill out a Fragebogen (often 131 questions) detailing their Nazi Party and organization memberships, employment, and activities to determine their suitability for public life and employment.

“The fragebogen is the greatest thing in Germany,” said the sergeant who came out from his desk with a long questionnaire of the type developed by US immigration inspectors. If they get past this, he says, they can hold any job they want. If they don’t, they can’t have any position where they employ labor or exercise a skilled trade or profession. They can’t do nothing but dig ditches, and if they lie on their fragebogan we have them up in court and they don’t get off easy. Every man or woman who has any position of authority has got to make out a fragebogan. If it turns out they are big Nazis it’s mandatory arrest. If they are small Nazis, they report to the labor gang. Everybody gets frageboganed sooner or later. Then we know what’s what.

Along the road, men and women, bundled up in heavy clothes and bowed under the weight of rucksacks, carried bundles of sticks. Their forests ought to be saving them in this winter. If they can’t get coal, they’ll at least have wood. But it’s hard to get the wood into the cities.

The trouble is all the foresters turned out to be Nazis. With denazification we are having trouble finding anybody who knows how to get the logs out.

“Frankfurt resembles a city as much as a pile of bones and a smashed skull on the Prairie resembles a prize Hereford steer, but quite enabled streetcars packed with people jingle purposefully as they run along the cleared asphalt streets. People in city clothes with city faces and briefcases under their arms trot busily about among the high rubbish piles, dart into punched out doorways under tottering walls. They behave horribly like ants when you have kicked over an anthill.”

“At every intersection there’s a traffic cop in blue uniform with a long warm overcoat. The traffic cops are the happiest looking people in Frankfurt. They are warm. They are fed. Their uniforms are clean. And they can order the other Germans around.”

Dos Passos speaks to the director of the zoo who tells how he saved some animals and some have died from cold.

“The more I see the more I hate the krauts for having made us do it.” shouts an American man.

*John Dos Passos (1896–1970) was an American novelist, journalist, and political commentator best known for his modernist U.S.A. trilogy—The 42nd Parallel, 1919, and The Big Money—a sweeping portrait of American life in the early twentieth century. An experimental writer, he blended fiction, biography, newsreels, and stream-of-consciousness to capture the forces shaping modern society. Politically radical in his early years, Dos Passos sympathized with labor movements such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and sharply criticized war, corporate power, and government repression, themes that run powerfully through the trilogy and define his enduring place in American literature.

a picture rarely, if ever, seen. The horror of the holocaust is reflected in repercussions upon the entire nation, even on those who did not know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Flo didn’t believe Germans who said they didn’t know about the Holocaust. She thought they were all culpable.

LikeLike

Flo was there and saw. I believe her. Guess I was trying to be “innocent t

LikeLike

Very interesting article. The was all new to me; I liked the description of the peasants and the denazification Questionnaire. Wow! Thanks again for sharing. Minerva

>

LikeLiked by 1 person