Chapter One

Dear Readers,

As I delved into my mom’s scrapbook from her time as a Red Cross “donut girl” in Europe during WWII, I began to wonder what motivated her to sign up for a job so close to the front lines in the war. What were Americans in small towns thinking about the wars in Europe and how were they affected? I was moved to look into my mother’s childhood and young adulthood in Yakima, Washington, and that research resulted in my last essay, Make America White Again, about the roots of racism in my hometown. I just read a fascinating book of creative nonfiction, We Were the Lucky Ones, by a young author, Georgia Hunter. It started as a blog about her Polish Jewish family and how they escaped the Holocaust during the war. That book inspired me to look deeper into my own family history.

So before I jump into WWII, I want to explore what my mother and her family’s lives were like as Europe was gearing up for war and the US was still stuck in the Great Depression. I chose to tell their story in one day, July 27, 1938, in five short chapters. Chapter One follows.

A Day in the Life of the Wick Family

July 27, 1938 started out hot and it just got hotter. Flo and her younger sister Betty had left the window in their upstairs room open all night but when the alarm woke them the room was still hot.

Flo had come in late the night before after Betty was asleep. When they were both awake she confronted her sister.

“Where were you yesterday? I came by the butcher’s to see if you wanted a ride home after work. Were you with Cecil?”

Betty’s face reddened. “Well….”

“He’s a married older man, Betty. He will destroy your reputation.”

“There is nothing going on between us. He just likes my company and he gives me things. Look what he gave me.” Betty opened a small box to reveal a gold necklace.

“This is terrible,” rasped Flo. “You must never accept these things from him. Return it to him and hope Mama never sees it.”

“But I don’t want to give it back,” complained Betty. “Look, here’s proof I’m a good girl.” She pulled from a large envelope a certificate signed with three names. It was titled The Senior High Society of Christian Endeavor DIPLOMA and it certified that “Betty Wick has for three years been a member of the above mentioned society of the First Presbyterian Church of Yakima, Washington, and that now she is affectionately graduated and earnestly commended to the Young Peoples Society of Christian Endeavor.” It had the gold corporate seal of the church with a red and a white ribbon pasted on.

“I’m sorry,” said Flo, gently putting a hand on Betty’s shoulder. “You must return the necklace. Tell Cecil your family says these gifts are not proper.”

Flo did not know what to do with her younger sister who, at only 16, seemed so very different from herself. But she loved her dearly and put some effort into protecting her from their mother’s wrath. Their Swedish mother, Gerda, had early on been influenced by her own sister Ellen who had joined the Pentecostal church and who believed that movies, dancing, playing cards and makeup were deadly sins. Flo and Ruth, the oldest sisters, had been most affected by their mother’s religious piety, which forced them as teenagers to lie about attending movies and to wipe off makeup before going home. By the time the youngest sister, Betty, came along, Gerda’s strict rules had relaxed but she still expected rigorous moral standards to be met.

The sisters each had their own bed ever since their two other sisters, Ruth and Eve, had taken live-in housekeeper jobs. Ruth had recently returned to the family home when she got a job as a stenographer. She now slept in one of the downstairs bedrooms. Betty, who was still in high school, had shared a bed with Eve as a child and Flo and Ruth had slept together. As kids, the four sisters had all shared the one big attic room accessed by a narrow unlit stairway from the kitchen. Gerda, a master of many skills, had hung cheery yellow flowered wallpaper, painted the fir floor a dark red and made a braided oval rug from scraps of wool left over from old clothes people had given her. One light bulb hung from the ceiling in the middle of the room. It cast light through the window into the yard at night indicating that Flo was reading instead of sleeping. Their father, Ben, would see it and call up the stairs, “Turn off the light.” Sometimes she did, recalled Ruth.

Neither sister wanted to get up. Betty liked to sleep in whenever possible, but that was rarely allowed in this household where early-to-rise was the rule. Each had her chores, although Flo, now the main breadwinner in the family, was exempt from most household chores. Gerda took care of the cooking and canning, shopping, washing, ironing, sewing and knitting of clothes, gardening and cleaning, with some help from the girls. Ben was still recuperating from a serious heart attack, which had landed him in the hospital a couple of months before.

The sisters took turns using the indoor toilet and sink in the downstairs bathroom where they also dumped their chamber pots. Bath day was Saturday and all family members used the same water from the little tank in the kitchen heated by the wood stove. The youngest went first with poor Dad last. Sponge baths at the sink supplemented bath day during the week.

Flo was feeling sticky and grimy on this Wednesday. To make matters worse, she saw blood in the toilet. Her period had started, which meant she’d be in pain with cramps for the next couple of days. She found the bottle of aspirin in the medicine cabinet above the sink and swallowed two pills, taking the bottle with her. At least she didn’t have to wear rags as she had when her periods had first begun, but Kotex pads were just one more expense to deduct from a tight budget. She found the box of Kotex hidden behind folded towels in the linen cabinet and took several to hide in her bag to take to work, making sure she was not seen. Menstruation was something to be hidden and not talked about, except with her sisters.

Flo was glad for the family’s indoor bathroom and running water. In their last home on the chicken farm in Meadowview, Oregon, they’d had only an outdoor privy with a Sears catalog for toilet paper and a water pump near the back porch. She returned to the bedroom to dress.

“How was your gathering last night?” asked Betty.

“It was great fun. We took the potluck out to Mrs. May’s lawn. We’re planning for the summer party next weekend up in Naches.”

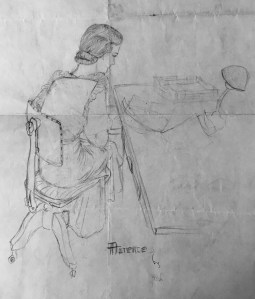

Flo had been out the night before with her sorority sisters at their bi-monthly meeting. She had pledged the working girls sorority, Epsilon Sigma Alpha, in 1933 and become the chapter president in 1936, organizing the social outings as well as discussion groups and business meetings. She was now a central person in the sorority and in the Business and Professional Women’s group, representing them at conferences around the state and at national events. She was a busy woman, working 44 hours a week as a stenographer as well as spending many hours doing organizational work and singing in the Presbyterian church choir.

Flo pulled newly bought cotton underwear from their shared dresser. Since she had been working she’d been able to afford her own underwear and some clothing, although Gerda sewed most of her wardrobe. Betty still wore the underwear Gerda had made from bleached flour sacks—crude brassieres, underpants and garter belts.

Flo picked out a white cotton blouse and darker-colored mid-calf cotton skirt to wear to work. It would be hot in the State Highway Department office too. As she rolled on rayon stockings to her knees, she thought about their father, whose health had been poor for the past several years. He had gone back to working as a bookkeeper and part-time teacher after his heart attack because the family needed his income. During her school summer vacation Betty had been helping him with the bookkeeping job at a butcher shop. Flo wished he didn’t have to work at all.

Their wardrobes may have been skimpy but the one thing the sisters had plenty of was shoes. Flo loved shoes that showed off her shapely ankles and legs. The year before, she had won a year’s supply of shoes for a slogan she had composed for Fashion Week. Her winning slogan, out of 40,000 entries, read: “I like Paris Fashion shoes because…their smartness and quality make feet fashionably well-shod and comfortable….Their reasonable price keeps them within my budget…yet does not cramp their style.” She had allowed Betty to pick out one pair of the eight she had won and the shoes still graced their shared closet. Flo was always submitting essays, ditties and slogans to contests, and she seemed to win most of them. The year’s supply of shoes was the prize she was most proud of.

As they each combed and shaped their short dark hair into place before their shared mirror, Betty tapped Flo’s arm. “What’s eating you, sis?”

“Oh, I’m just worrying about Dad. I know he says he feels better but he seems so fragile since his heart attack.”

“Well worrying won’t get you anywhere. Let’s put on a happy face for him.”

Chapter Two: https://mollymartin.blog/2017/03/15/breakfast-at-16th-avenue-july-27-1938/