Reinventing Some Holiday Myths

Dear Friends,

As we construct our ofrendas for Day of the Dead, decorate our yards for Halloween and celebrate the pagan holiday Samhain, I’ve been thinking about two other holidays we celebrate this time of year–Indigenous Peoples’ Day and Thanksgiving. This is a story about how the meaning and celebrations of American holidays can evolve to reflect new understanding of our history.

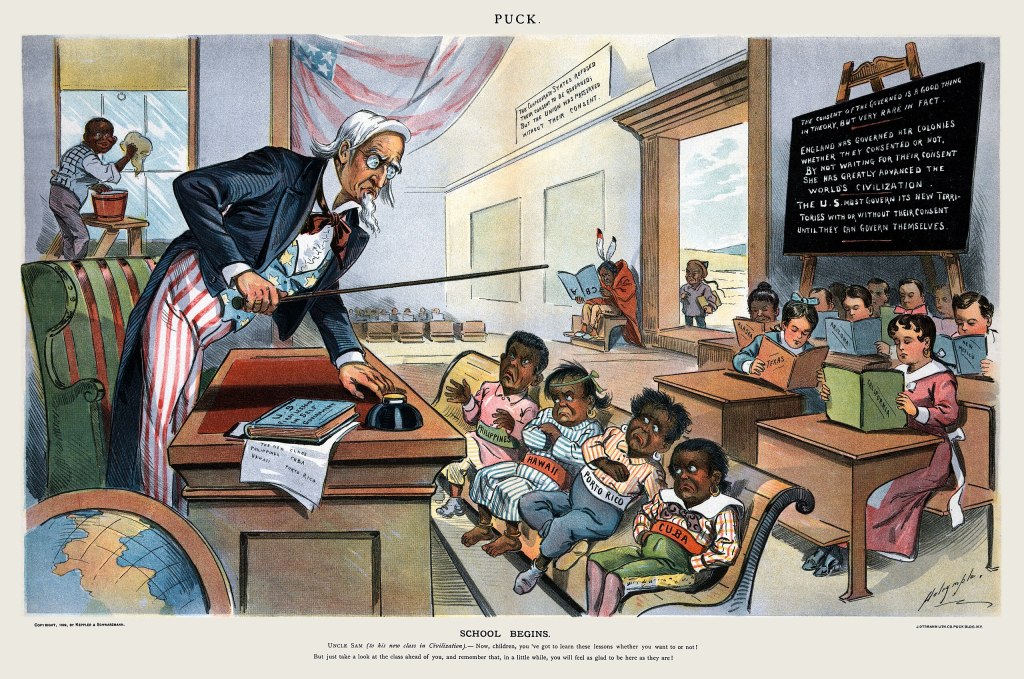

As we learn more details about our history, in the last few years Americans have been rethinking the stories connected with Thanksgiving and Columbus Day.

My generation of students learned to recite, “In 1492 Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” We learned about the Nina, the Pinta and the Santa Maria and that Christopher Columbus “discovered America.”

In elementary school in the 1950s I participated in those Thanksgiving pageants in which you were either a Pilgrim—boys with black buckled hats and shoes, girls in long, aproned dresses and bonnets—or an Indian with feathered headband and tomahawk. The story we enacted was a peaceful meeting and feast between Indians and pilgrims just off the Mayflower. It was the beginning of a happy long relationship between settlers and Indians.

Sadly, almost all of what we were taught was incorrect and incomplete; the myth conveniently left out the parts about genocide, slavery and land theft.

It turns out that Christopher Columbus was a homicidal tyrant who initiated the two greatest crimes in the history of the Western Hemisphere–the Atlantic slave trade, and the American Indian genocide. It’s not dissing Italians to say we no longer venerate this colonizer. Over the last few decades, Columbus Day has evolved into Italian Heritage Day in many locales.

And we are witnessing a movement to honor Native peoples on Columbus Day. It originated in 1989 in South Dakota during its “Year of Reconciliation,” in an effort to atone for terrible history.

The phrase “merciless Indian savages” is written into the Declaration of Independence. That says all we need to know about how the founders of our country viewed the indigenous people in this land.

For centuries, the American government saw Indians as the enemy, sponsoring their slaughter and “removal.” Through a series of notorious atrocities, including the Trail of Tears, the Sand Creek Massacre and Wounded Knee, (and in California, our own Trail of Tears in 1863, and the Bloody Island Clear Lake massacre in 1850, among others) the United States adopted an official expansionist policy of discriminating against Native Americans in favor of encouraging white settlers in their territories. This policy led to the subjugation, oppression, and death of many Native Americans, whose communities still feel its effects. Only in 1924 were Native Americans allowed to become citizens of the United States, and it took decades more for all states to permit them to vote.

But as we Americans acknowledge this history, our contemporary view of Native Americans is changing.

Congresswoman Norma Torres (D-CA) has introduced legislation to establish Indigenous Peoples’ Day as a federal holiday. Now, at least 13 states and over 130 cities have adopted Indigenous Peoples’ Day or Native American Day. In 2021, President Joe Biden formally recognized Indigenous Peoples Day.

Here in Sonoma County indigenous people are well integrated into our local culture and community events. Tribes are consulted by land keepers and planners. Colleges, libraries and nonprofits sponsor classes about indigenous culture. My wife Holly and I attended the Indigenous Peoples’ Day gathering at Santa Rosa Junior College, which featured native dancing, music, drumming, food, speeches and vendors. The SRJC also has a native museum whose latest exhibit features the stories and art of local basket weavers.

As with Columbus, Americans have been taught a false narrative about Thanksgiving.

Two different early gatherings may have inspired the American Thanksgiving holiday. At the first, in 1621, Wampanoagwere not invited to the pilgrims’ feast, but heard celebratory gunshots and came to the aid of the colonists. They had formed a mutual defense pact. Once there, the Indians stayed and feasted, but the feast did not resolve ongoing prejudices or differences between them. Contrary to the Thanksgiving myth, this was not the start of any long-standing tradition between the settlers and the Wampanoag tribe. The myth doesn’t address the deterioration of this relationship, culminating in one of the most horrific colonial Indian wars on record, King Philip’s War.

Ironically, Thanksgiving as a holiday originates from the Native American philosophy of giving without expecting anything in return. The Wampanoag tribe not only provided food for the first feast, but also the teachings of agriculture and hunting. Corn, beans, wild rice, and turkey are some examples of foods introduced by Native Americans.

The first written mention of a “Thanksgiving” celebration occurs in 1637, after the colonists brutally massacred an entire Pequot village of 700 people, then celebrated their barbaric victory, giving thanks to their god.

During Reconstruction, the Thanksgiving myth allowed New Englanders to create the idea of bloodless colonialism, ignoring the Indian Wars and slavery. Americans could feel good about their colonial past without having to confront its really dark characteristics.

For many Native Americans, Thanksgiving is a day of mourning and protest since it commemorates the arrival of settlers in North America and the following centuries of oppression and genocide.

Indian protests in the 1960s and 70s often attacked the Thanksgiving myth. In 1969 after natives took over Alcatraz, allies and Indians of all tribes came together for Unthanksgiving Day, a gathering that’s become a tradition, welcoming all visitors to a dawn ceremony on the island.

In 1970 during a Thanksgiving celebration in Plymouth, activists from the American Indian Movement stormed the Mayflower II ship and occupied it in protest. It was then that the United American Indians of New England recognized the fourth Thursday in November as a National Day of Mourning, to bring awareness to the long lasting impacts that colonization had on the Wampanoag and other Native American tribes. This year the in-person event will also be livestreamed.

Americans are told and we want to believe that we are the saviors of the world. But historical truth is far different.

Does the acceptance of Indigenous Peoples Day in place of Columbus Day and the updating of the Thanksgiving myth mean that we Americans are beginning to acknowledge our country’s history of imperialism and genocide? I hope so.

This time of year, and these two holidays, Thanksgiving and Indigenous Peoples Day, give us the opportunity to reflect on our collective history, to celebrate the beauty, strength, and resilience of the Native tribes of North America, and also to conduct our own rituals.

Long before settlers arrived, indigenous people were celebrating the autumn harvest and the gift of the earth’s abundance. Native American spirituality, both traditionally and today, emphasizes gratitude for creation, care for the environment, and recognition of the human need for communion with nature and others. I hope we can incorporate these ideals into our American harvest celebrations while we as a species still live.

Whether or not we cook a big turkey dinner, many of us practice Thanksgiving rituals. My and Holly’s ritual is to get together with our exes. We introduced them at a Thanksgiving dinner 13 years ago and they fell in love. We were surprised, and also delighted. Barb and Ana have become our exes and besties. We are participating in a lesbian tradition of incorporating our exes into our chosen families.

No matter where you are in North America, you are on indigenous land. In Sonoma County we live on unceded territory of the Pomo, Wappo and Coast Miwok tribes.

Good Samhain, Halloween, Day of the Dead and Thanksgiving to you all.

Love, Molly (and Holly)