Fear is moving up with us. Fear is right there beside you.

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 14

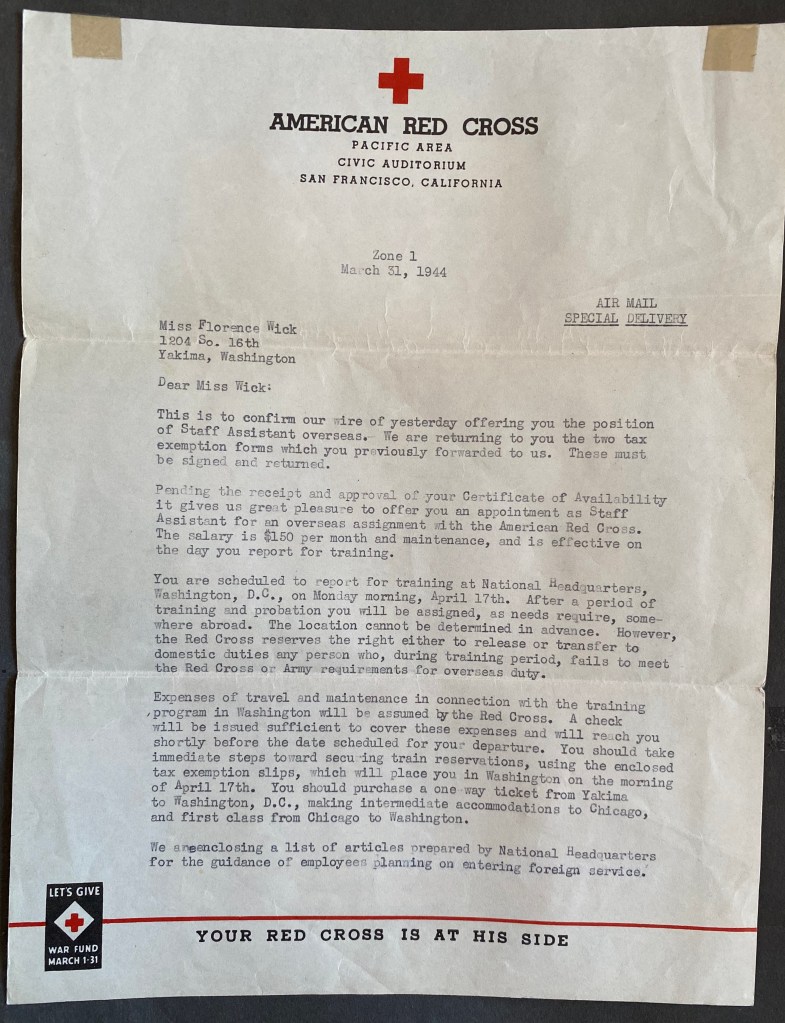

Audie Murphy’s autobiography To Hell and Back was shaped in collaboration with David McClure, a Hollywood writer who served in the Army Signal Corps and knows firsthand the shock of war. The book centers on the ordinary infantrymen of the Third Division, capturing their humor, fatalism, and endurance. In the battle scenes, the tone sharpens. At Anzio, Murphy describes the brutal churn of attack and counterattack in a landscape where the ground itself seems to resist survival.

“Light trembles in the east. To our left, an artillery dual is growing fiercer. We hear the crack and thunder of our own guns; the whine and crash of incoming German shells. (A soldier) stands in his chest deep foxhole and leans with his elbows on the bank. He studies the eastern horizon and shakes his head in mock ecstasy. “Gee!” says he, “another beautiful day.”

By afternoon, the order comes: attack!

“Fear is moving up with us. It always does. In the heat of battle it may go away. Sometimes it vanishes in a blind, red range that comes when you see a friend fall. Then again, you get so tired that you become indifferent. But when you are moving into combat, why try fooling yourself. Fear is right there beside you….

“I am well acquainted with fear. It strikes first in the stomach, coming like the disemboweling hand that is thrust into the carcass of a chicken. I feel now as though icy fingers have reached into my mid-parts and twisted the intestines into knots….”

Speech dies away as they approach the enemy line. Artillery fire slackens, and the men check their weapons one last time. Scouts creep forward. Everyone waits for the first eruption.

“This is the worst moment. Just ahead the enemy waits silently. It will be far better when the guns open up. The nerves will relax; the heart, stop its thumping. The brain will turn to animal cunning. The job lies directly before us: destroy and survive.”

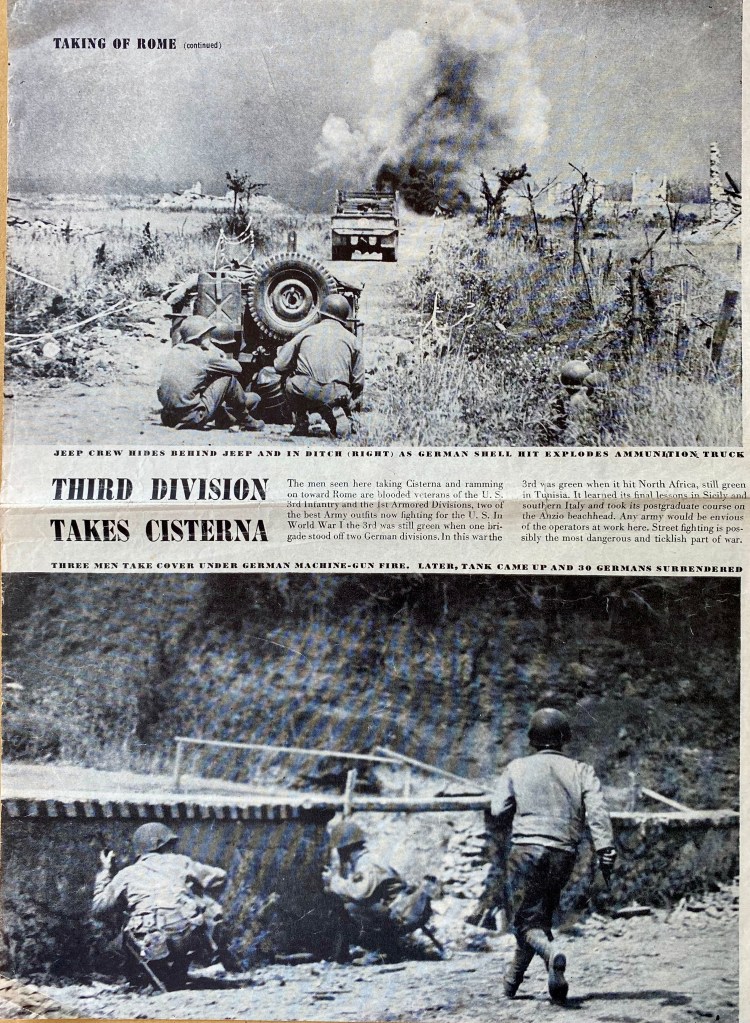

The scouts signal them on. Just as they inch forward, two hidden flakwagon guns open fire. One scout is hit squarely in the chest; his upper body disintegrates in an instant. The 20 mm shells, designed for aircraft, are used here against men, each strike exploding on impact. There is no time to think; the entire landscape erupts with automatic fire. Branches shear off the trees overhead. Bullets pitch into the earth. Two men in the open scramble for the shelter of a small rise, but the gunner finds his range. They collapse, still at last.

The scouts signal them on. Just as they inch forward, two hidden flakwagon guns open fire. One scout is hit squarely in the chest; his upper body disintegrates in an instant. The 20 mm shells, designed for aircraft, are used here against men, each strike exploding on impact. There is no time to think; the entire landscape erupts with automatic fire. Branches shear off the trees overhead. Bullets pitch into the earth. Two men in the open scramble for the shelter of a small rise, but the gunner finds his range. They collapse, still at last.

A massive shell shrieks overhead and Murphy dives into a roadside ditch. The blast lifts him, knocks him senseless, then dumps him back into the mud. When he crawls forward to check the man beside him, the soldier lies dead with no visible wound—killed by pure concussion. Murphy marks the body for the burial team, driving the bayonet into the bank and tying a strip of white cloth to its tip.

German artillery intensifies. The earth becomes a furnace of shrapnel and fire. Limbs and fragments of bodies fall back to the ground with the dirt. Night offers no rest. The foxholes are cold, wet, and shallow. Rumors spread that the entire front has been forced back. The men are told they will attack again in the morning.

Exhausted and hollow-eyed, they rise. The numbness of survival replaces fear. When the order comes, they move like machines. German artillery meets them immediately, and the men spread across open fields, advancing from one shell crater to the next. Medics, unarmed and clearly marked, fall beside the wounded they are trying to save. The cycle continues: advance, retreat, advance, retreat. After three days, not a single yard of ground has been gained.

This was the story of Anzio. The Allies made the first amphibious landing on the beachhead on January 22, 1944 and the battle didn’t officially end until the liberation of Rome June 4, 1944.

The 3rd Infantry Division suffered over 900 casualties in one day of combat at Anzio. This was the highest number of casualties suffered by any US division in a single day during the war. The Allies sustained 40,000 casualties at Anzio.

The battle leaves no one unchanged. Anzio becomes not just a place, but a memory carved in mud, smoke, concussion, and loss—the memory of men who advance, fall, rise again, and return to the line because there is no choice except forward.

Quotes are from Audie Murphy’s autobiography, To Hell and Back

Ch. 15: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/03/16/rome-is-liberated-by-allies/