In a Letter Home Flo tells of Clubmobilers’ Life

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 56

Searching through archives kept by my cousin Gail (our mothers were sisters), I was delighted to find two letters written by my mother, Flo, to her mother, Ruth–one in August, 1944 and the other dated February 1, 1945. These have helped to give a more personal perspective to the ARC women’s lives. Here Flo muses about death and war while describing everyday life of the clubmobilers in the French mountains. She reveals that the wedding rings her fiance Gene had ordered from home had arrived the day after he died.

February 1, 1945

Dearest Ruth:

“Your letter of December 4 just reached me a few days ago – mail has had no priority and many of my Christmas greetings and cards arrived just now. However, packages came through well and I had all of yours from home in time. Thanks for the grand gifts, Ruthie – they were so appreciated. The sweatshirt was the envy of everyone (we wear them with our clubmobile uniforms) and I love the slip and underwear. Was down to “Rock bottom.” Your cake was eaten so quickly, all I can remember was that it was very good.

(Flo admires pictures of Ruth’s three girls)

“Thanks for the sympathy and your philosophical comments. I’ve “recovered” if you can call it that, but it was a cruel shock, and I wouldn’t want to go through it again. We see friends “go” so often these days that death is close always, though it never ceases to be tragic and futile. Gene’s first sergeant, a fine, handsome boy, who has a lovely wife and darling three-year-old daughter, and who was always so good to me, has been killed in the last few days. That’s the way it goes – they leave one by one, particularly in a combat outfit like theirs and my division. The few who have survived almost 3 years of constant fighting, are very tired and should go home, but probably won’t until the war is over.

“Gene’s family write to me often and find it hard to believe he is gone. They are sending me the rings he bought and which arrived over here the day after he was killed and were returned to them. Somehow, I don’t want them, but they think I should have them.

“We are in the mountains and have had a lot of snow the last month but a very welcome chinook wind has melted much of it, which makes driving on these roads less hazardous. Evidently the French ski a great deal around here and there are some attractive ski places, as well as good slopes. I never seem to have time to try them out, but some of the boys did and had a fun time.

“Our infantry is “busy” as usual, and we are waiting to see them and feed them donuts again. It is always hard, after a session in the lines, to see them again and find friends are missing.

“After a brief session of gaiety in Strasbourg our social life has been reduced to practically nil. Contrary to many ideas, we do not indulge in much social activity; the men are pretty well occupied, you know, and it is only when they have a brief rest that we have a dance or two.

“We continue moving frequently and just made another one today. Lately we have been living in French homes and are coming to know the natives quite well. I can’t speak much French, but can understand it quite well when they slow down to 50 mph instead of 90.

“Right now we have rather cramped quarters in a home which is filled with refugees who were burned out of their homes when the Germans left. Many of these people have lost everything and many, of course, being Alsatian, are torn between being Frenchmen or Germans.

“We’ve been “up front” a few times – within a few hundred yards and within firing range, but it looks no different from any other place, unless the towns have been shelled (and most of them have). There are no trenches, like the last war, And much of the time, it moves so fast, there are no foxholes either, though they “dig in” if they are holding a line. We were shelled in one of the villages the other day, though it happened so quickly, we didn’t have time or sense enough to be frightened. It isn’t fun, even if it seemed funny afterwards.

“There have been setbacks for the Americans in France, but we are happier about the situation now and the Russian drive is encouraging too. I doubt if I will be home for some time yet, but then, I certainly won’t be among the first to leave.

“My package – sent to Mom – with gifts for you all should have reached you by now. I hope they serve the purpose; it is difficult to find anything worthwhile here – their stores and supplies have been hard-hit.

“I like to hear about your kids and other news of the people at home. Betty doesn’t write very often, but mom is wonderfully faithful and takes care of me over here almost as well as she did at home.

“If there are any of my clothes – hats, shoes etc. that you can wear and want to, help yourself, because they will be out of style when I get home and I’d like to have you get some use out of them. Just go down and see what you can use.

“Very seldom see a movie (last one was “A guy named Joe” which I saw with Gene and which he didn’t like; he was killed a few days later and the show haunted me).* They have very few good ones and very few period. Read seldom, too, and even more seldom hear a radio, so you see my mode of living and entertainment has changed considerably.”

*(This was a popular war movie starring Spencer Tracy, Irene Dunne and Van Johnson about an American pilot who is killed when his plane goes down after bombing a German aircraft carrier. Then he is sent by “the general” back to earth to train a pilot in the South Pacific war. At the end he’s still dead. The Irene Dunne character gets to fly planes too. The screenwriters were Dalton Trumbo and Frederick Hazlitt Brennan.)

“We have the fellows at the 2.M. (not sure what this means) in quite a bit, toot around the country in our jeep whenever we can and manage to never be bored, which keeps us happy, I suspect.

“I like the work and love the boys. Life gets very simple and fundamental, if you can understand that, and we share many of the same experiences, which makes everyone a friend.

“Eve was fine but busy, and Paris is the same lovely lovely city, though they have food shortages, little fuel and all that. It didn’t seem too unusual to see Notre Dame Cathedral on Christmas morning, but in years to come it will be quite a recollection. Eve and Janet were very good to me and it was like home to see them. Janet’s husband was wounded tho not seriously and she was quite upset. I hope to go back in the spring– It would be even nicer there then in the lovely park.”Maybe my own luck will change one of these days; at least I can share sorrow and sincerely sympathize with others who are hit by the tragedy of war. It makes me even a worse “softie,” but there are many to share it with.”

Ch. 57: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/09/23/black-and-japanese-soldiers-in-wwii/

Mom used to tell us kids stories from her time in the Red Cross in Europe and my brother Terry reminded me of a favorite.

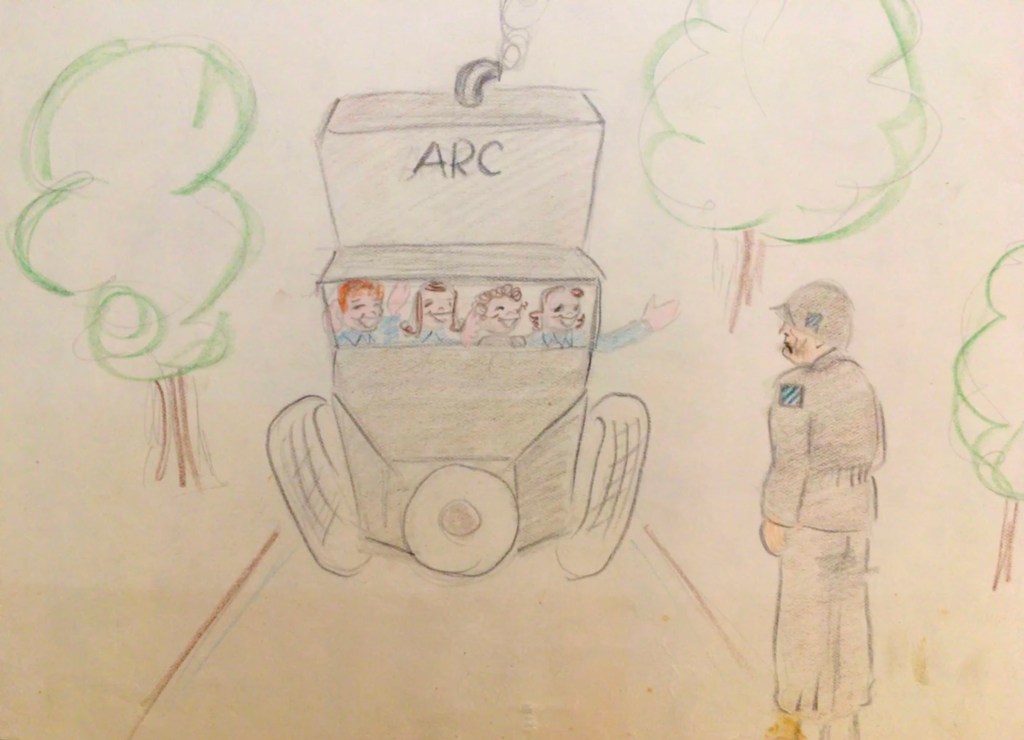

Flo and her ARC team were driving their clubmobile toward the front lines to serve returning soldiers. Somewhere on a lonely French country road, far from anything resembling safety, the truck suddenly died. Though they’d been trained in basic vehicle repair, nothing they tried would bring it back to life. In the distance, artillery boomed, each blast sounding closer than the last. The four women stood with the hood up, poking and prodding, running through every trick they’d been taught.

Then an American Army jeep rattled up. The sergeant driving had such a thick New York accent they could barely understand him, but he clearly knew his way around an engine. He took a quick look under the hood and announced, with total confidence, “It’s the coils, goils.” The line struck them as so absurd they collapsed into hysterical laughter. The sergeant, baffled, had no idea what was funny. Moments later the truck roared back to life, and they got out of there as fast as they could.