“Gay Man Stabbed in Heart Survives,” read the front-page headline in the BAR, a gay newspaper I picked up while strolling on Castro Street.

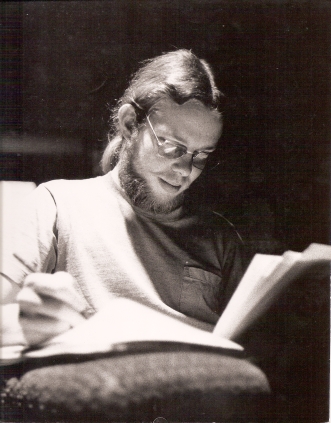

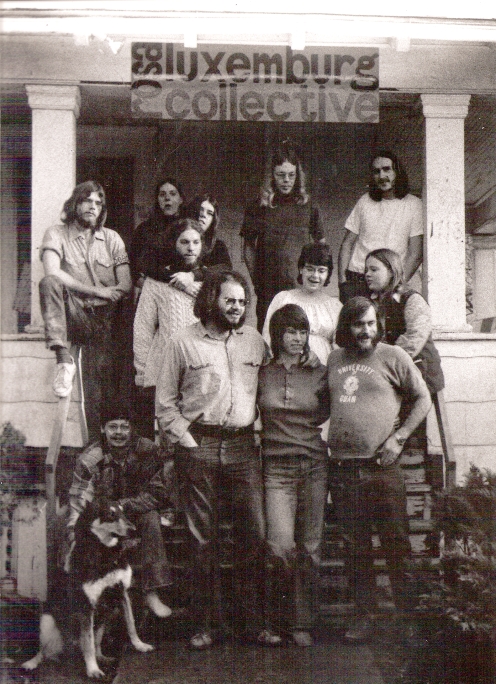

Then I looked at the picture. It was my old college roommate Larry Johl. I recognized him immediately from his long very blond hair. As students at Washington State University we had lived together in the Rosa Luxemburg Collective in Pullman, Washington, a little town near the Idaho border. That was in 1973-74 before we had each decamped to the gay mecca of San Francisco. We had been in touch, and I had once been to his apartment on Broderick Street, furnished tastefully in deco style with castoff furniture and cheap (but not cheap-looking) window treatments.

Our get-together in San Francisco in the late ‘70s had revealed that Larry worked at a boring, low-paid office job in some bureaucracy. He described himself as a snow queen, meaning that he preferred to date black men. I later found out that snow queen was the term used to describe black men who prefer white men. The subculture’s term for white men like him was grunge queen, but I think he probably didn’t use it because of its racist overtones. He had a cute, angelic-looking boyfriend whose picture graced his bedroom chest of drawers.

I should note here that Rosa Luxemburg, whose giant portrait graced our dining room wall, was a Polish revolutionary socialist theoretician who was assassinated in 1919. Our hero. Margarethe von Trotta made a film about her https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLo4TuBRN6U.

When I thought back to our collective living arrangement at Rosa’s, in a huge house with 11 others, I remembered Larry had a thing for black men even then. It was Larry who introduced us to the music of the gay icon Sylvester. How did Larry discover him? How did Larry discover gay culture? It seemed like he had emerged a full-blown raging queen from his tiny desolate hometown of Soap Lake, in the eastern Washington desert, the middle of nowhere. He told me that as a kid he’d been a big fan of Elizabeth Taylor and had filled secret scrapbooks with her pictures cut from magazines. Perhaps he’d been a queen from birth, living testimony for the argument for nature over nurture.

Larry didn’t come out to us at Rosa’s but we knew. He personified all the stereotypes—limp wrists, lilting voice, and the neatest room in the house. In the collective, Larry was the roommate most concerned with beauty and fashion. He bought hair products by the case, it seemed. His hair really was strawberry blond. But it did look bleached, so perhaps he bleached in secret and then tried to mask the consequences with product. One time when we were on a road trip, all piled into a VW bus, Larry got out to smoke a joint and lit his hair on fire. Which must prove something about product.

Our Welsh roommate Keith couldn’t believe Larry’s wealth of information about popular culture. “He never reads. How can he know so much?” It was true. We seldom saw Larry studying. How did he pass his exams? He seemed much more interested in music. One semester he spent his student loan money on a stereo. I guess after that he depended on the kindness of strangers, or the kindness of friends.

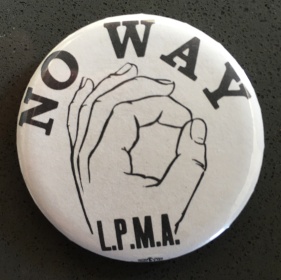

Larry was central to our countercultural and political activities. He excelled in tasks organizational. His specialty was the media blitz. With our dissident friends, we had formed the League for the Promotion of Militant Atheism in response to a student Christian crusade. The Jesus freaks’ slogan was “One Way” and they’d proselytize holding up an index finger. It was annoying as hell. Our slogan became “No Way,” our sign a zero made with index finger and thumb. During registration week when students poured into the student union and all the organizations set up their wares at the entrance, Larry sat at our table and showed slides of all the churches in town, a tape of Elton John’s Burn Down the Mission playing continually in the background. Then, when we staged a debate about the existence of god, Larry took on media/outreach and managed to fill the auditorium to capacity.

We were desperate to change the direction of national politics, refusing to pay the federal phone tax that funded war and staging die-ins at ROTC functions. The FBI came knocking at the door after Larry sent a threatening letter to president Nixon. I don’t believe he was arrested. He had only put in writing what we were all thinking.

I think my brother Don would say Larry brought him out of the closet. Don didn’t live with us at Rosa’s but he visited frequently. In those days our sexual identities weren’t so clearly defined. We all experimented with gay as well as straight sex, although in retrospect the women seemed much freer than the men. The women swung like kids on a new play set, while the men tended to gravitate to one corner or the other of the sandbox. Neither Larry nor my brother Don was ever interested in women at the orgies we sponsored. They would carry on afterwards dishing male anatomical details, which I invariably missed.

After I saw his picture on the front page of the BAR, I called Larry. He was out of the hospital. He told me he had been cruising Buena Vista Park at 2 a.m. when he was attacked and stabbed. His attackers then tried to pull off his leather clothes. He was saved by a punk couple who got him to the hospital just in time. He had lost almost all the blood in his body. The gay bashers were never caught.

I asked Larry what he intended to do next. He said he was just going to live life as he had, maybe with more passion and vigor. “I could get hit by a bus tomorrow,” he told me cheerfully. He figured all the time in the future was free. He had been spared death, for the time being.

By that time in the early 80s we knew about AIDS but there was no test available yet and of course there was no treatment. Gay men were just dying. You would see your friend, a young man you sang with or worked out with, looking healthy and vibrant. Then he would get a diagnosis and two weeks later he would be dead.

When I asked my brother Don to tell me his memories of Larry, he remembered that they had seen each other in the late 80s. By that time Larry must have known he was HIV positive. He told Don that when he died he wished to be cremated and he wanted someone to distribute his ashes from a window of the 24 Divisadero, the bus that took Larry from his neighborhood in the Western Addition to the gay bars in the Castro. He said he wanted all the queens to prance behind the bus and stomp him into the pavement with their platform shoes.

I never saw Larry again, and when I tried to call, his number had been disconnected. I couldn’t find mention of him anywhere. I was pretty sure he had died of AIDS. The BAR had been printing obits for gay men since 1972, but it never published his. Did he, like many gay men, go back home to die? That was hard for me to imagine. Did he die alone or did he have a network of friends to care for him? Was he one of the ones who perished within weeks? Don and I felt negligent, that we had not come to his aid when he was dying. I sure hope someone did.

Eventually I found a notice of his death in the Ephrata, Washington paper, a slightly larger small town near Soap Lake. He had died in 1990. He was 39. But there were no details and so I just had to imagine his last years and days. Also in the Ephrata obits I found a Carl A. Johl, born 1914, who died in 2009 at the age of 94. I guess Carl was Larry’s father.

Some of the Rosa Luxemburg Collective roommates reunited again after 35 years. I had to come out to them as a lesbian. Then it fell to me to explain Larry’s fate to this assemblage of straight folks. I fear I failed.

Lesbians and gay men lived in different universes, different cultures, which we were continually inventing back in the 1970s and 80s. As a close student of lesbian feminist culture, I had no trouble discoursing on its development. But I was instantly aware that I didn’t really know the culture Larry lived in. How to explain his cruising escapades and his obvious sluttiness? The story seemed to suggest that he was responsible for his own demise, at least as I imagined my straight comrades might see it. We were a progressive bunch who believed in free love and revolution, rejecting nuclear war and the nuclear family. Still, I sensed disapproval in their shocked emailed responses.

Or was it something like envy? Larry had found himself in San Francisco and he was finally free to live an openly gay life. I think he was happy. Perhaps he and I were two collective members who succeeded in transcending the conventional lifestyle that we countercultural dissidents had all worked so hard to reject.

The 24 Divis is a crosstown route that goes from the rich white neighborhood of Pacific Heights clear down to the poor black neighborhood of Bayview-Hunters Point. It was the bus that for decades carried me from my neighborhood in Bernal Heights to the Castro to gay bookstores, bars, demonstrations, and film festivals at the Castro Theater. My wife and I often stop for a beer at Harvey’s just to cruise the crowd on the corner through its big windows.

The scene is still vibrant and colorful, but there are times, especially in winter, when walking in the Castro I see the ghosts of the young men who died of AIDS and then I’m overwhelmed with grief, so very aware of all that we have lost.

This story originally aired on the MUNI Diaries podcast, hence the references to the 24 Divisadero bus. I had such a hard time reading that last paragraph without breaking down crying. I share this grief with an entire generation of people who lived through the AIDS years. We have not forgotten.