The 6888th Battalion cleaned up the mail mess

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 43

In October 1944, after her fiancé Gene was killed, Flo had trouble reaching her mother. The wartime mail system was broken.

This wasn’t just a personal problem—it was widespread. Soldiers on the battlefield were not receiving letters and packages from home. Mail, the lifeline of morale, was piling up undelivered. The men risking their lives for democracy weren’t hearing from their families, and the silence was taking a serious toll.

Flo had noticed the problem early. In letters and diary entries beginning in May 1944, shortly after arriving in Italy, she often mentioned that no mail had come. She didn’t complain—Flo wasn’t a complainer—but she noted it again and again. Others were more vocal. Across the war front, soldiers and Red Cross workers alike were frustrated and bitter. What began as a logistical issue had grown into a morale crisis.

The Army didn’t officially acknowledge the scale of the problem until 1945—by then, millions of letters and packages were sitting in European warehouses, unopened and unsorted.

Then came the 6888th.

The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion—known as the “Six Triple Eight”—was a groundbreaking, all-Black, multi-ethnic unit of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), led by Major Charity Adams. It was the only Black WAC unit to serve overseas during the war.

Their mission: clear the massive backlog of undelivered mail under grueling conditions and extreme time pressure. They worked in unheated warehouses, with rats nesting among the mailbags, and under constant scrutiny from a military establishment rife with racism and sexism. But they got the job done—sorting and forwarding millions of pieces of mail in record time.

Their work restored something vital: connection. And morale.

The 6888th wouldn’t have existed without the efforts of civil rights leaders. In 1944, Mary McLeod Bethune lobbied First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to support the deployment of Black women in meaningful overseas roles. Black newspapers across the country demanded that these women be given real responsibility and not sidelined. Eventually, the Army relented.

The women of the 6888th made their mark. Many would later say they were treated with more dignity by Europeans than they had ever experienced in the United States.

If you haven’t seen the Netflix movie The Six Triple Eight, it’s well worth your time.

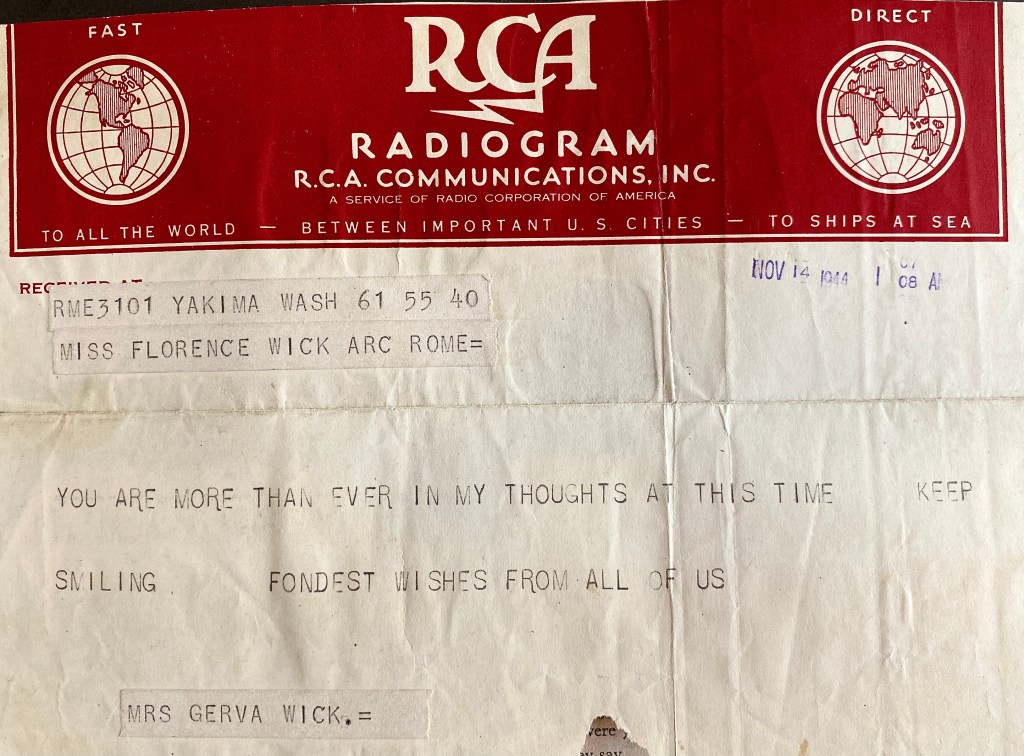

Back in October 1944, the broken mail system meant heartbreak and silence for Flo. How long did it take for her disconsolate letter to reach her mother? Gerda telegrammed back on November 14—more than two weeks after Gene had died.

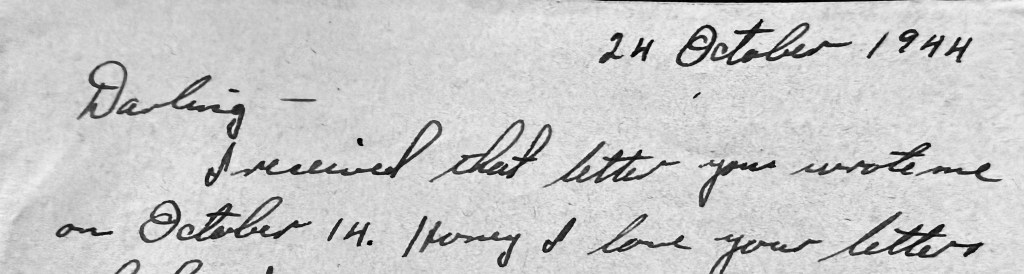

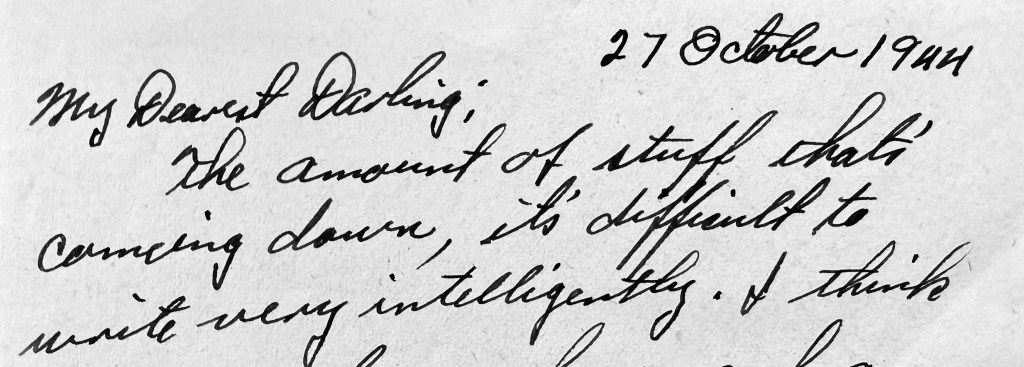

When did Flo receive Gene’s final letters? She saved the ones he wrote on October 24 and 27, but it seems likely she didn’t get them until after he was gone. He died on October 28, killed by a mortar shell. That same day, Flo wrote in her diary, “Mail from home today.” She didn’t mention anything from Gene.

In his last letters, Gene wrote about his army buddies. He worried about his little sister wanting to marry. He dreamed of peace, and of a life with Flo in the Northwest:

“Back there where the country is rugged and beautiful. Where you can breathe fresh, free air; and fish and hunt to your heart’s content. You know honey, a place where we don’t have to sleep in the mud and cold, and where the shrapnel doesn’t buzz around your ears playing the Purple Heart Blues.”

Even in the chaos of war, he tried to stay lighthearted:

“I’m writing on my knees with a candle supplying the light. I hope you are able to read it. My spelling isn’t improving very much; but with the aid of a dictionary I may improve or at least make my writing legible.”

He hoped Flo had managed a trip to Paris, and that she’d seen her sister and brother-in-law stationed there. He looked forward to getting married:

“Honey I haven’t heard from home on the ring situation yet, but I expect to before long. When I do, I shall let you know right away. I’m hoping we can make it so by xmas, if not before.”

But his letters also reflected the danger he was in:

“It’s very difficult to write a letter on one’s knees, as you probably already know. Ducking shrapnel and trying to write just don’t mix. I do manage to wash and brush my teeth most every day.”

“It’s too ‘hot’ for you to be here. I’ve got some real stories to tell you when I see you next—if I’m not too exhausted. You don’t know how close you’ve been to—I hadn’t better tell you.”

Gene’s voice comes through with vivid clarity, even across 80 years and a broken mail system.

That words eventually reached soldiers in the field and their families back home is thanks, in part, to the quiet heroism of the 6888th—who made sure love letters, grief, and hope could still find their way through a war.

Ch. 44: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/08/02/born-in-oregon-buried-in-france/