Chapter 7 My Mother and Audie Murphy

On the packed trains from Yakima to Chicago and Chicago to D.C. were many others traveling to war. It seemed to Flo like the whole country was traveling east. Many on the train were wives of servicemen. Some fellow travelers were American Red Cross workers. Two sisters, identical twins, got on at Spokane on Washington’s far eastern border. Louise and Lucine Suksdorf grew up in the tiny Eastern Washington town of Rosalia. They were heading to D.C. and the ARC training school as well, and the women bonded immediately.

Flo was no rube. She had taken the train cross-country to YWCA meetings in Columbus, Chicago and Minneapolis, and she’d visited New York City in 1941. She had disembarked at Grand Central Station, the biggest train station in the country, but that was before the U.S. had entered the war. Nothing prepared her for Washington’s Union Station in April 1944, ground zero in war-related transport.

Stepping down from the train, the women found themselves in what felt like an anthill. The Beaux Arts vaulted ceiling arches of the station lent a turn-of-the-century air to the scene of rushing bodies down on its marble floors. They were just three of thousands (millions?) of people milling in all directions. The station itself was alive with frantic activity, its denizens dressed mostly in khaki uniforms. Soon, Flo would be one of them, shipping out to some unknown theater of war, somewhere in the world.

The women had heard that the presidential suite in Union Station had been converted to a USO club during the war. They had to see it. Explaining at the door that they were about to enter service as ARC workers, they were ushered into the suite, admiring the opulent decorations. Service members in uniform lounged on leather-covered chairs and couches. They played cards and chatted at tables. This would not be Flo’s last encounter with the USO. She would work with the USO during her ARC service and she would later direct her own USO club back in Yakima after the war.

The Suksdorf sisters had received the same ARC letter as Flo and they would be staying at the same place while they went through the two-week training for overseas service workers. The Burlington Hotel was on 14th NW in downtown Washington, near the American University where they would attend training classes. The women succeeded in catching a cab to their destination, which was only a few blocks from the White House.

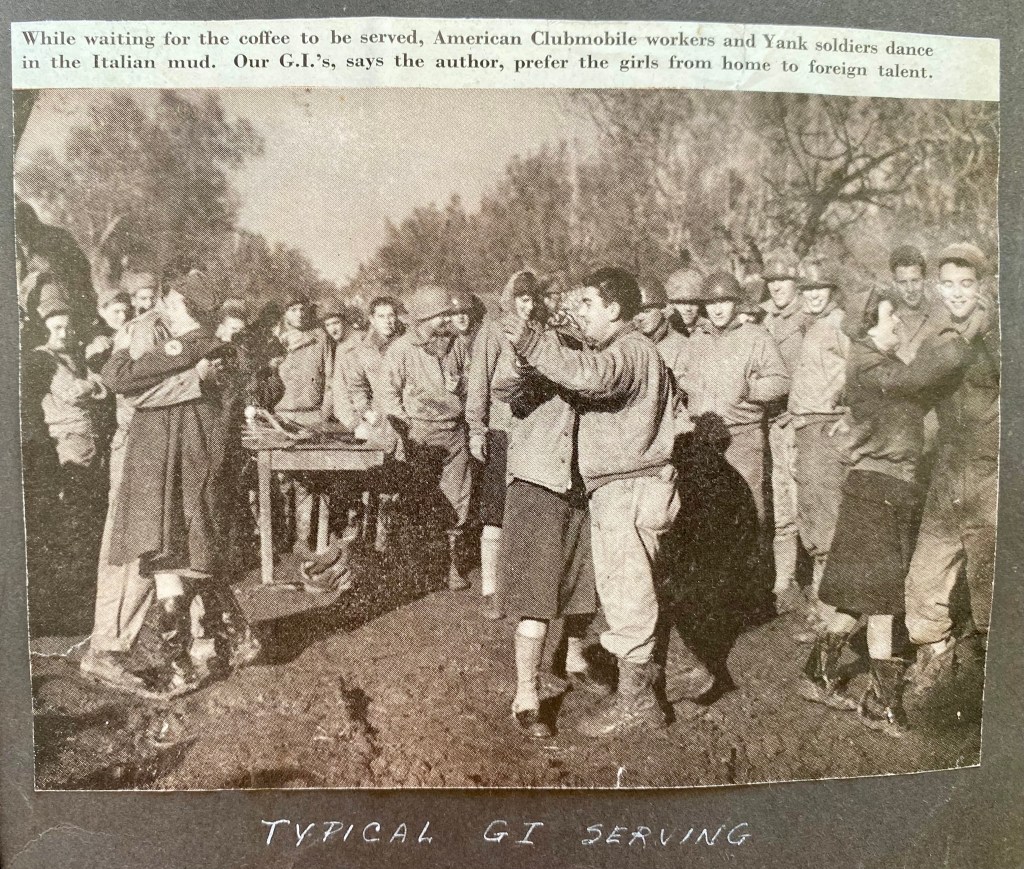

The women knew not where in the world they would be sent to work, but they kept close track of the war, raging in countries around the world. In April, 1944, in Europe and the Pacific, the war heated up. Bombs were dropped on cities; on April 18, the Allies dropped more than 4000 tons of bombs over Germany, the highest single-day total of the war so far. Submarines, liberty ships and destroyers were torpedoed and sunk, British and Indian forces fought against a Japanese offensive, Japan launched a series of battles against China, and Soviet forces invaded Romania. Hungarian authorities ordered all Jews to wear the yellow star. On the Italian front, the bloody battle for Anzio advanced.

Chapter 8: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/02/05/of-mud-mules-and-mountains/