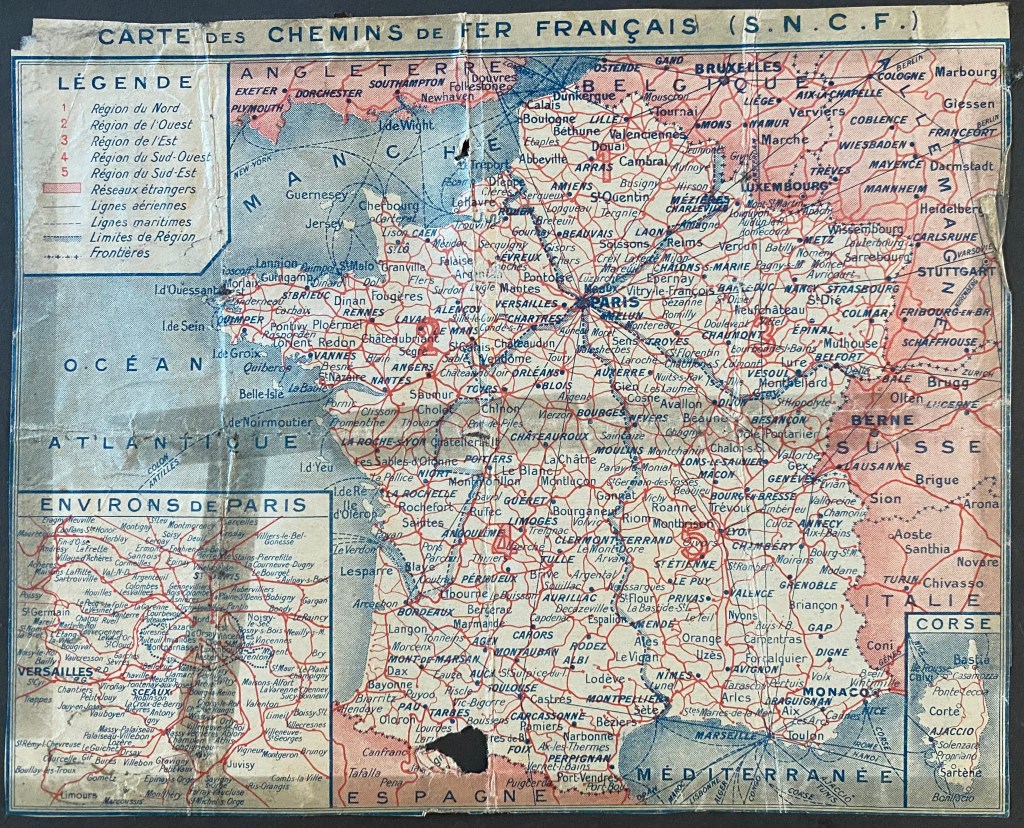

We crash into Besançon and fight until morning

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 30

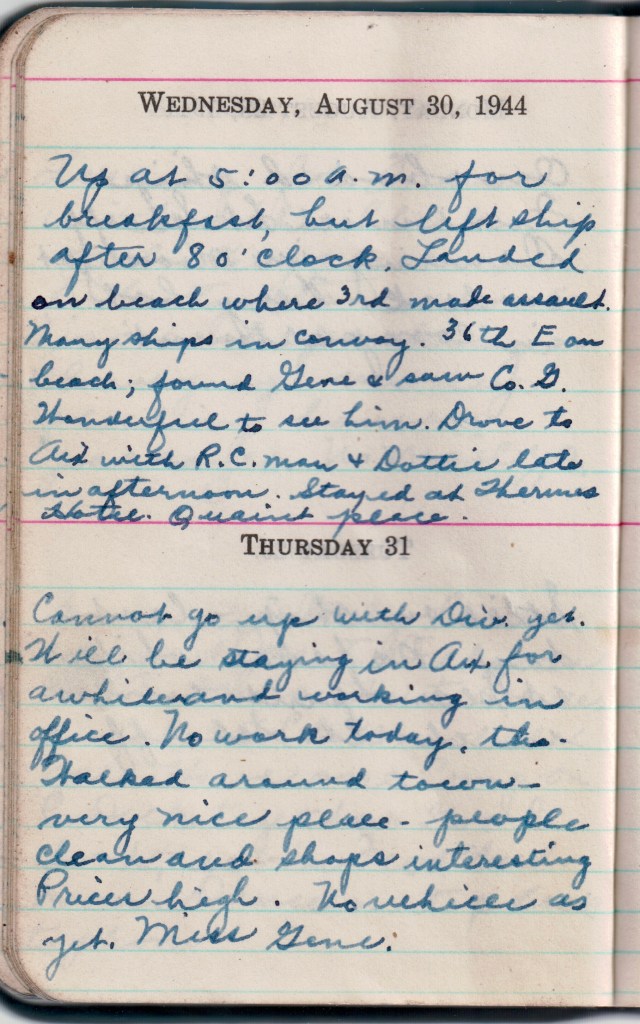

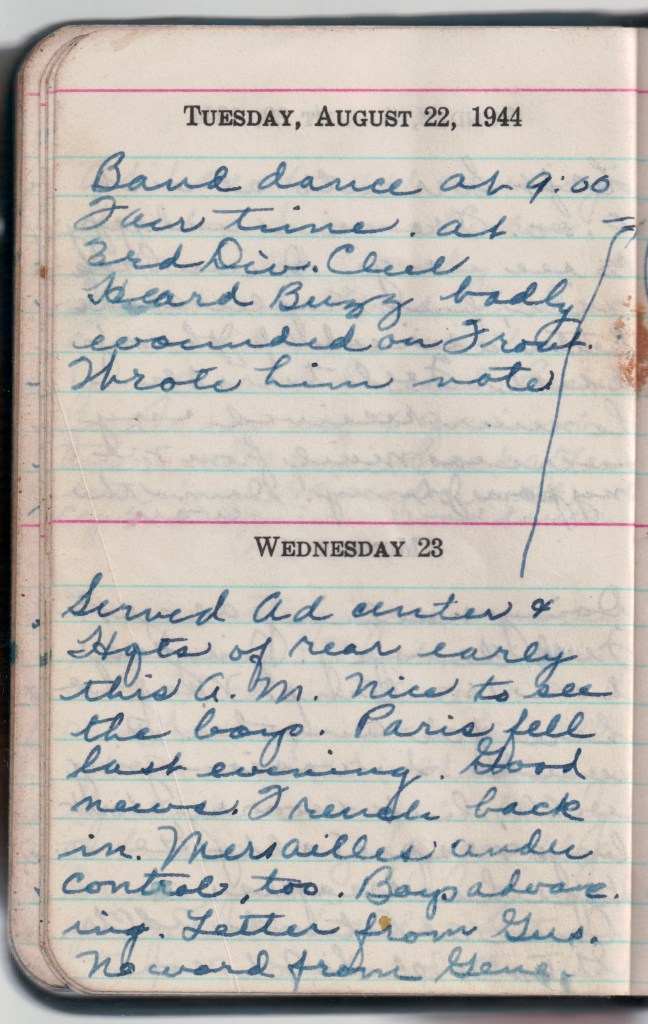

September 5, 1944. From Murphy’s autobiography To Hell and Back:

In a short while they are back in the thick of battle. The forward units knife through German lines, leaving pockets of resistance for the mopping-up crews. The noise of combat rises from every direction.

The swift advance has drained their energy and their supplies. Hungry and exhausted, they collapse along a roadside to wait for orders. Artillery thunders over their heads. They lie on their backs, listening to the shells crash forward into the hills.

Murphy and his crew seize an opportunity when a German supply truck rattles into view. They ambush it and find it loaded with bread and cognac. For a brief, stolen moment they eat, drink, and sing, the battle seeming almost far away.

That night they crash into Besançon and fight until morning. Within a few days the city is secured, and once again the pursuit of the retreating Germans begins.

Murphy’s platoon brings up the rear when a roadblock stops the company. Mortar shells begin peppering the earth. Murphy pauses to speak to a small group of soldiers, several of them nervously pale replacements, waiting for the fire to ease.

Nearly killed by a mortar shell

A mortar shell drops in almost without sound. It is practically under Murphy’s boots before he registers its arrival. He has just enough time to think, This is it, before the blast knocks him unconscious.

When he comes to, he is sitting beside a crater with the shattered remains of a carbine in his hands. His head throbs, his eyes burn, and he cannot hear. The acrid, greasy taste of burned powder coats his tongue.

He runs his hands down his legs, methodically checking. Both limbs are there. But the heel of his right shoe is gone, and his fingers come away sticky with blood.

A voice filters dimly into his fogged brain: “Are you all right, Sergeant?” He wipes the tears from his stinging eyes and looks around. The sergeant who spoke and the young recruit beside him are dead. Three others are wounded. All had been farther from the shell than he was.

When a mortar detonates on contact with the ground, its fragments shoot upward and outward in a cone. Murphy had been standing close to the base of that cone and caught only the lightest edge of the fragmentation. Had he been three feet farther away, he knows he would not be alive.

During World War II, concussions resulting from mortar attacks were a significant source of traumatic brain injury (TBI). Soldiers experienced symptoms like headaches, dizziness, poor concentration, and memory problems following exposure to blasts, even without visible head injuries. The term “shell shock” was originally used in WWI to describe these symptoms, but was later replaced with terms like “post-concussion neurosis” in WWII. Head injuries from mortars contributed to a significant percentage of medically treated wounds during the war.

Murphy spends a few days in the hospital, not because of his brain injury, but because his foot was wounded. Then he’s back in the lines.

Ch.31: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/06/04/evidence-of-nazi-war-crimes/