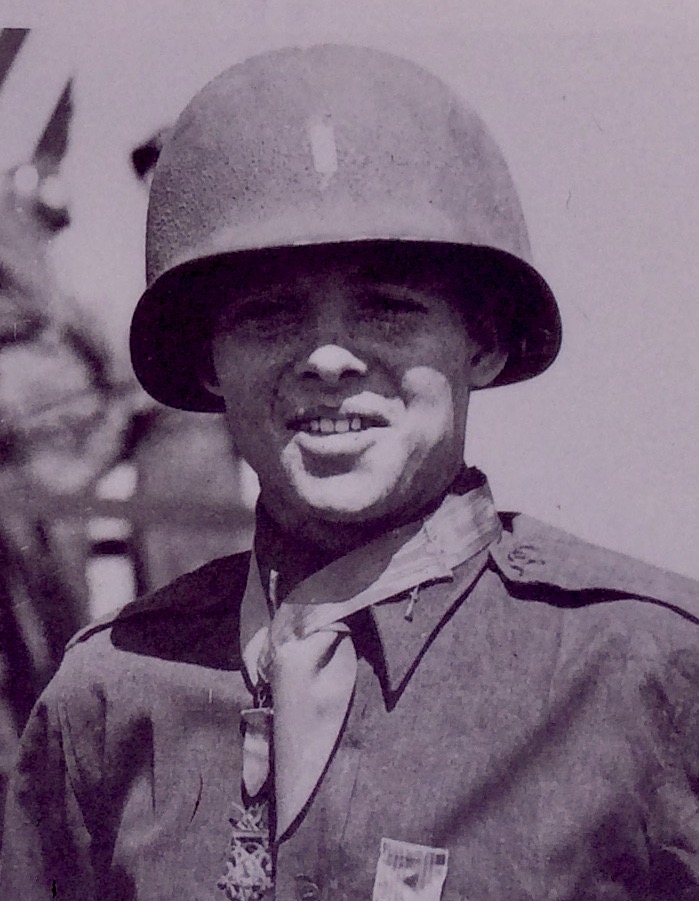

Chapter 6: My Mother and Audie Murphy

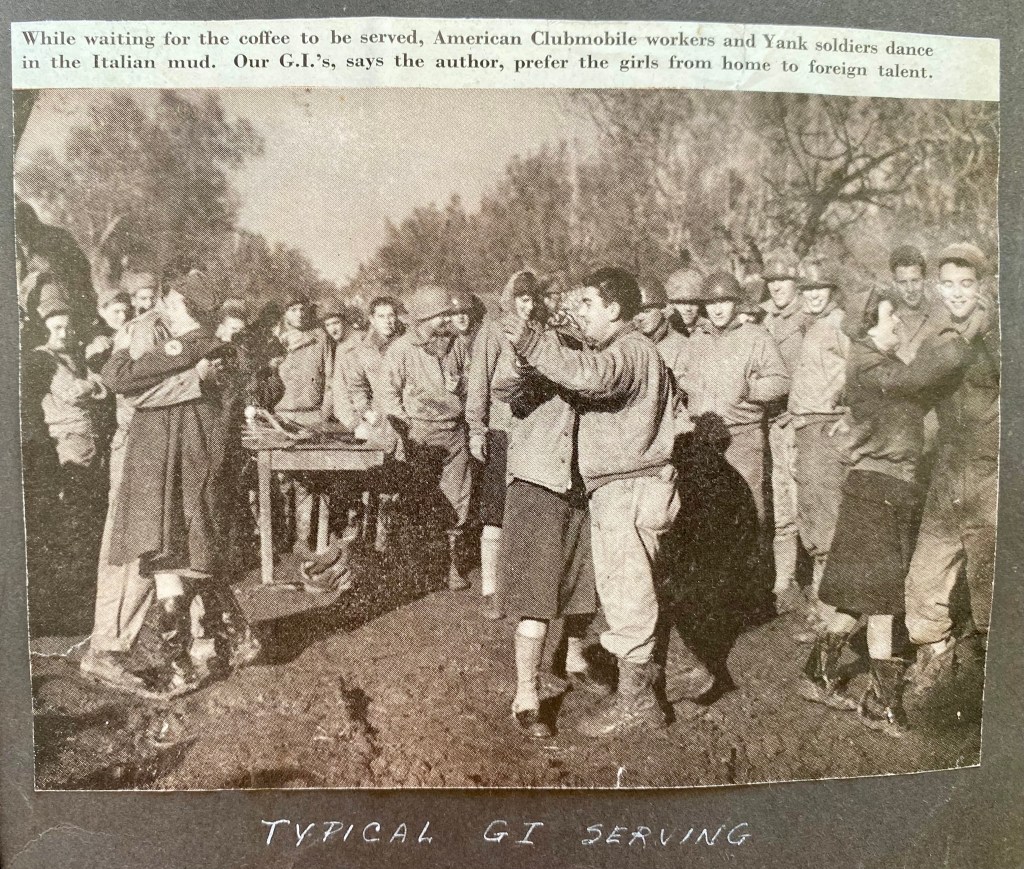

October 1943. Murphy lands at Salerno during the Allied invasion of the mainland.

Italy has surrendered, and the road to Rome appears deceptively simple. Yet, the journey is anything but straightforward. Many thousands of lives will be lost on the road to the Eternal City.

“We land with undue optimism on the Italian mainland near Salerno. The beachhead, bought dearly with the blood and guts of the men who preceded us, is secure….We are prepared for a quick dash to Rome,” wrote Murphy in his autobiography, To Hell and Back.

This was far too optimistic. The Third Division will be fighting and dying on the Italian beaches and mainland until May, 1944.

The troops of the Third Division must first push through Salerno, cross the Volturno River, and take Anzio, Mignano, Cassino, and Cisterna before they can approach Rome.

Audie Murphy leads a small, diverse squad of men. Among them are an Italian immigrant, a Cherokee Indian manning the machine gun, an Irishman, a Pole, a Swede, and a Smoky Mountain bootlegger.

Members of Murphy’s squad begin to fall almost immediately. One soldier hesitates under heavy Nazi fire as he runs for a bridge and is cut down. The squad carries his body to the highway where it can be easily found.

“In death, he still bears the look of innocent wonder. He could not have lived long after tumbling. The bullet ripped an artery in his throat,” wrote Murphy.

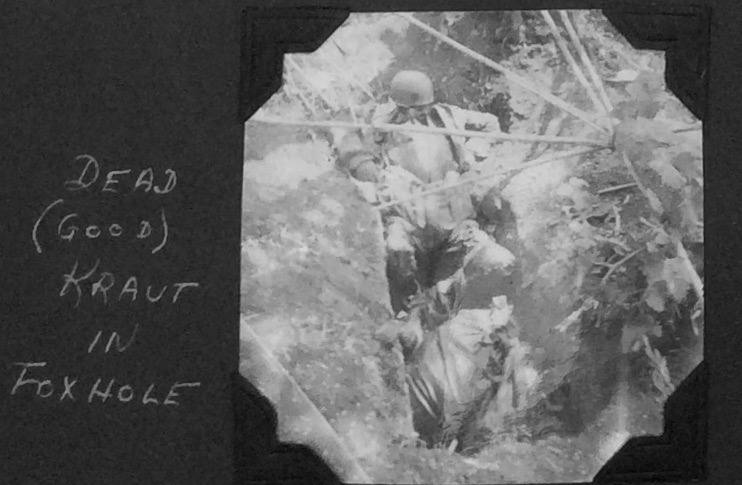

Another fighter takes out a German machine gun nest and a foxhole with grenades, killing five Germans.

The small victory is short-lived.

Later, the five remaining men find themselves trapped in a cave, surrounded by the enemy. The cave is infested with fleas, and the men are bitten mercilessly as they wait, parched and desperate.

We come to know and care for the men in Murphy’s squad, only to witness their deaths or injuries that force them out of the fight. Murphy becomes the last man standing at the end.

“All my life I wait to come to Italy,” says the Italian soldier. “I write my old man that the country stinks. Wait till you get to Rome, he says. Wait’ll you see your grandfather’s place. Then you’ll see the real Italy.”

The Italian never makes it to Rome. After three days without water, he breaks under the strain, running out of the cave only to be hit and killed by enemy fire. “He has come home to the soil that gave his parents birth,” wrote Murphy.

Finally, American troops break through the German lines and rescue the remaining men. Relief arrives with rations, water, and ammunition.

The next morning, they cross the Volturno River and join the push toward their next major objective: the communications center at Mignano.

Quotes are from Audie Murphy’s autobiography, To Hell and Back.

Chapter 7: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/01/30/train-to-d-c-april-1944/