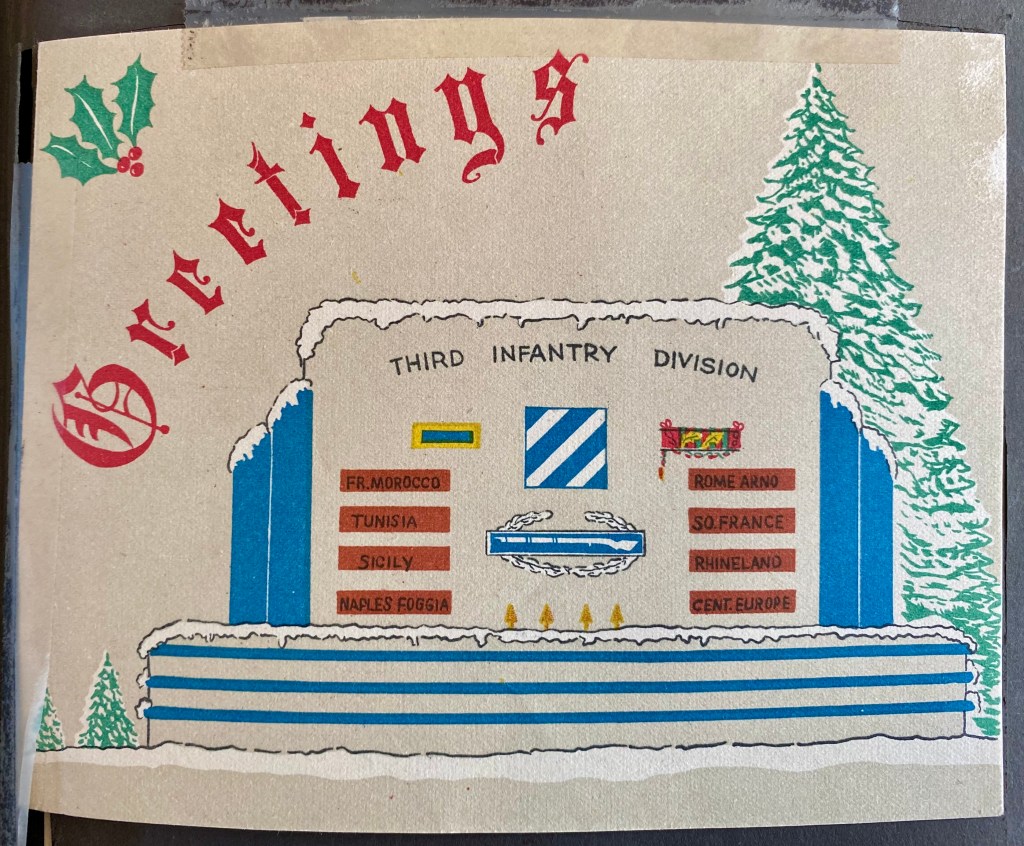

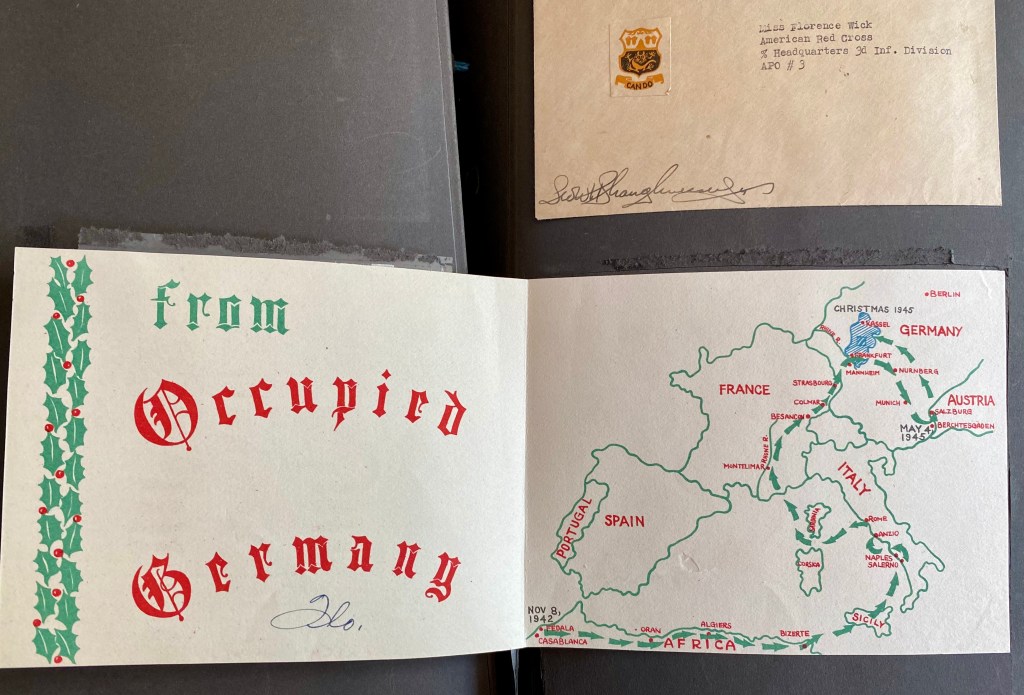

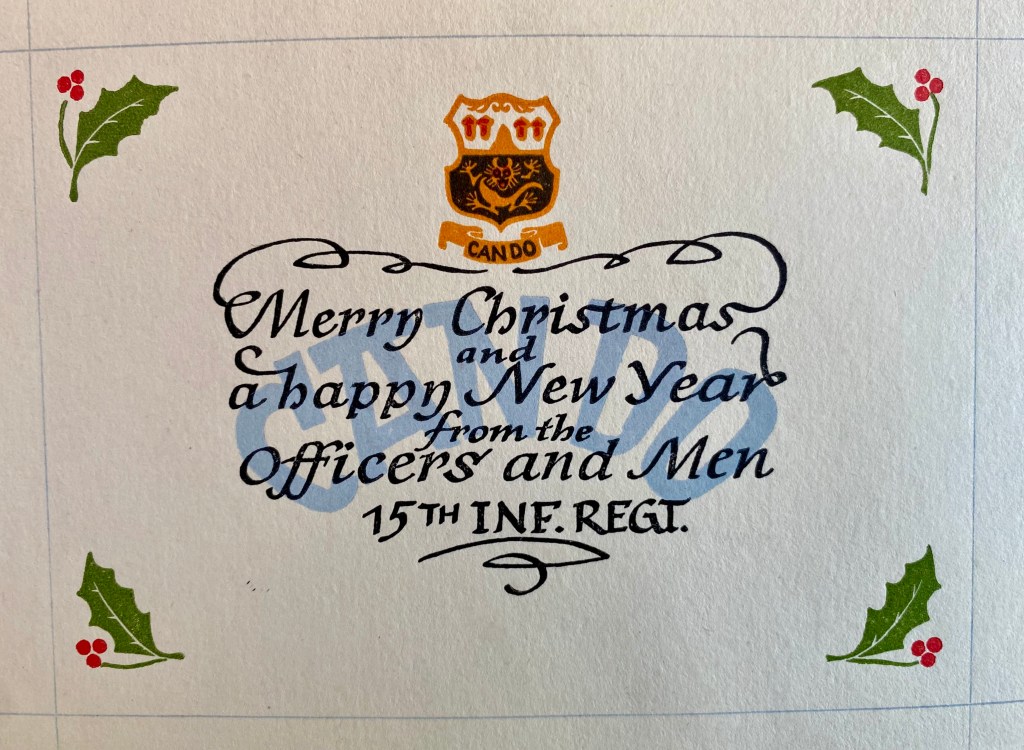

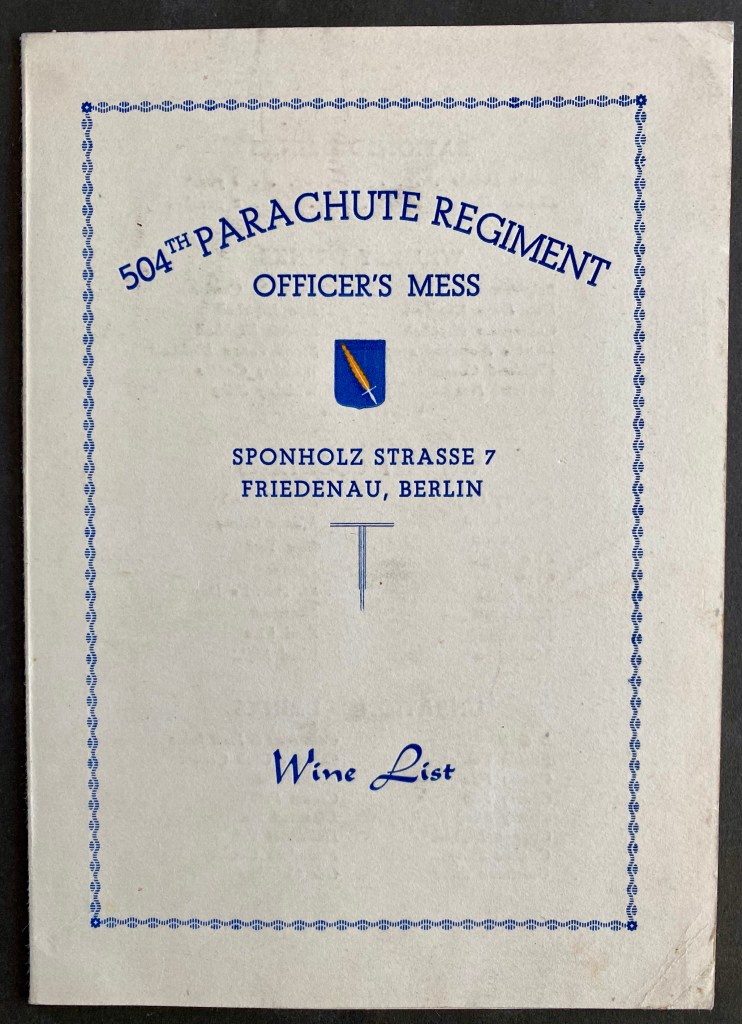

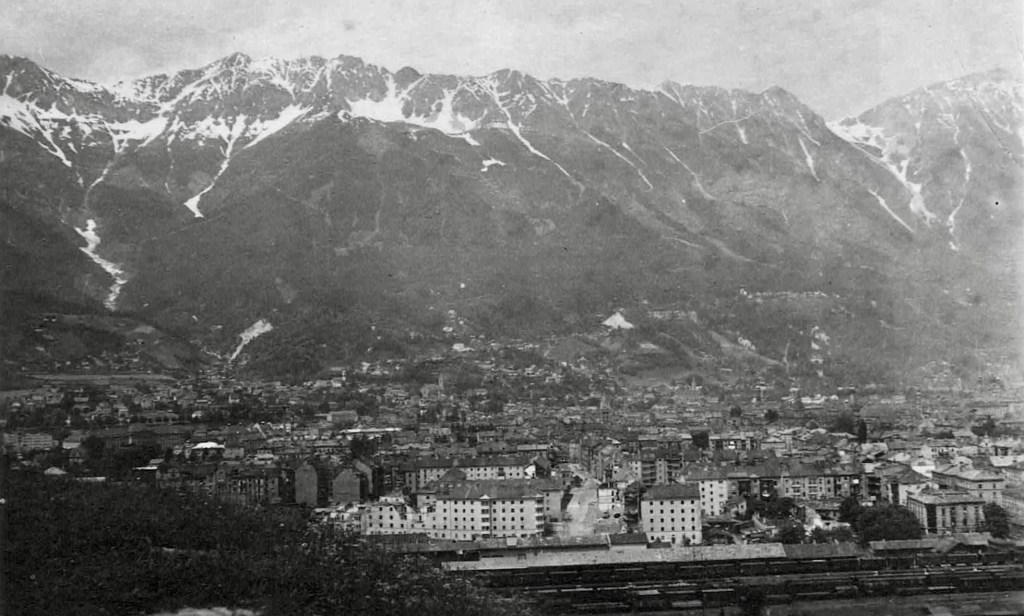

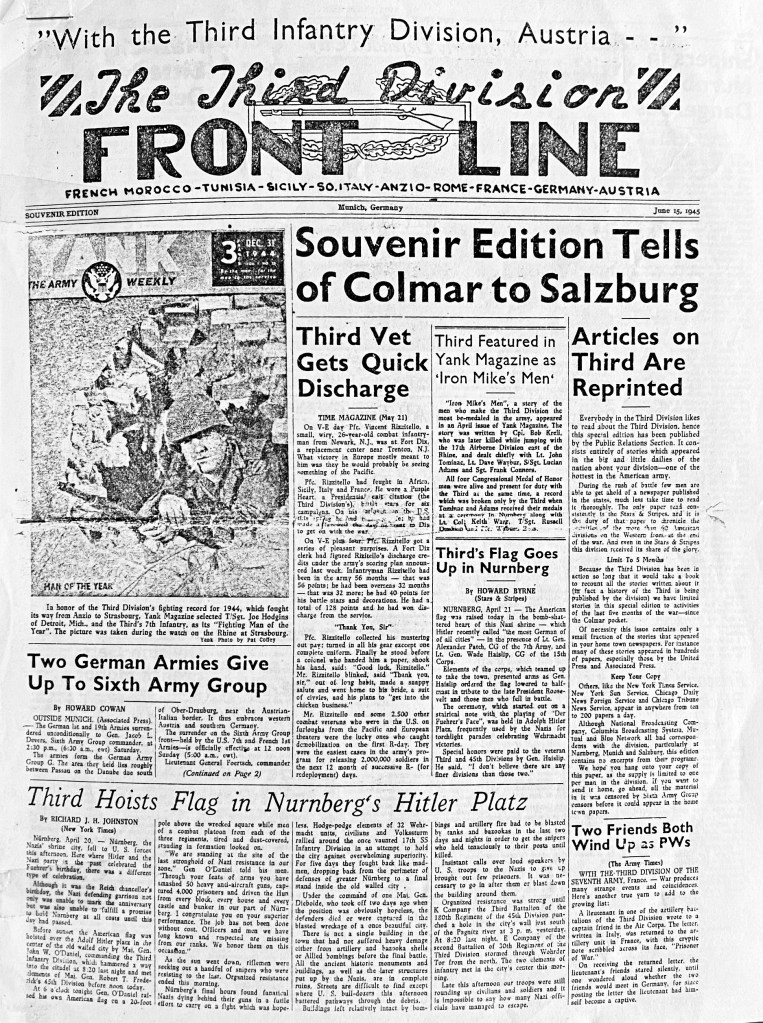

3rd Division souvenir paper tells history of the division

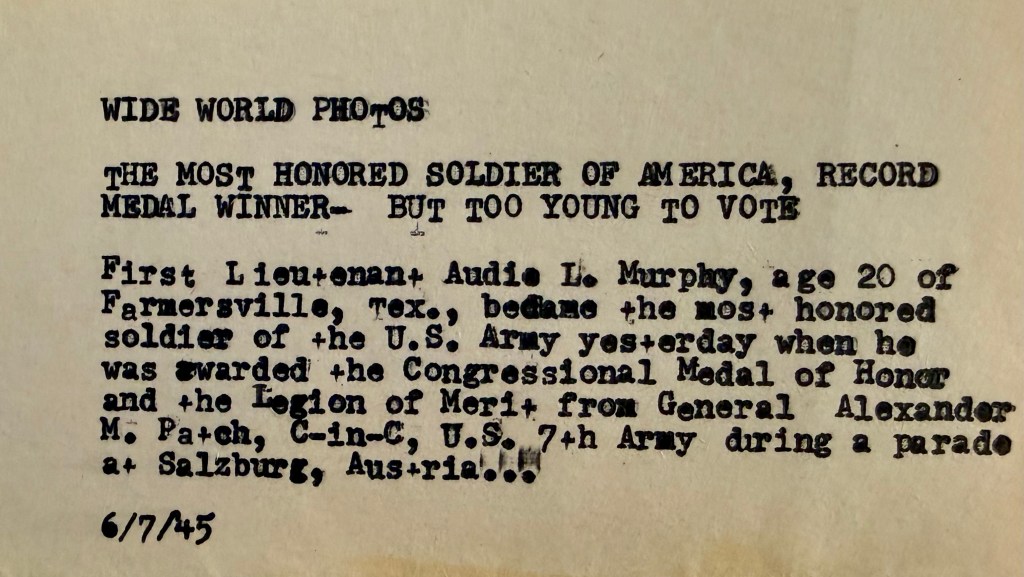

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 100

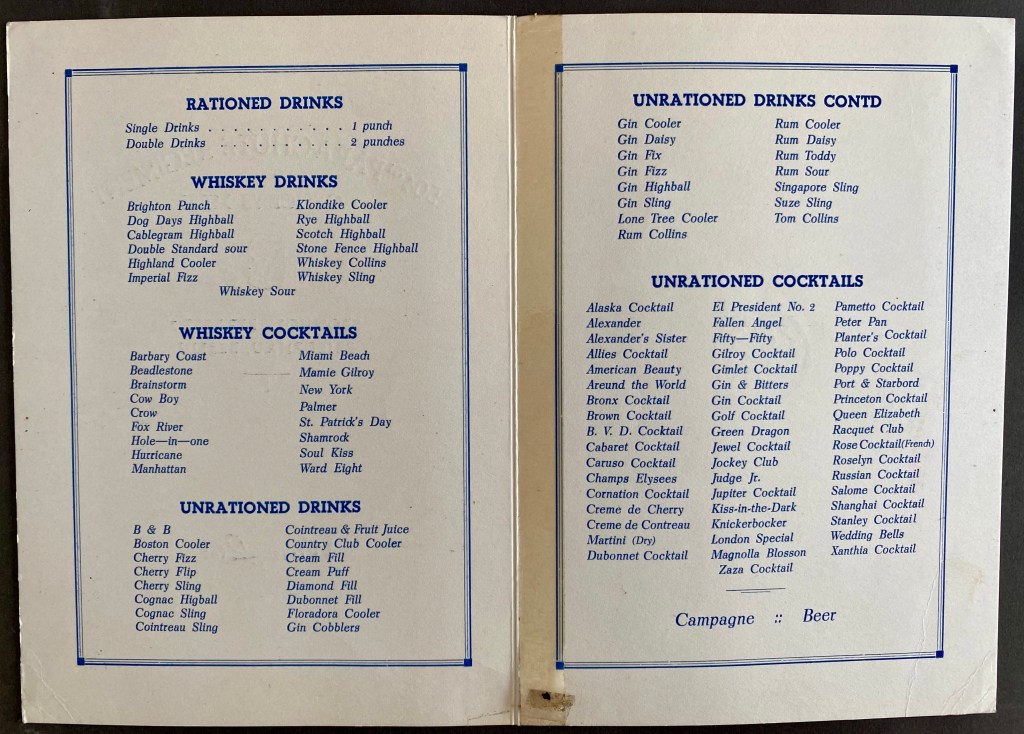

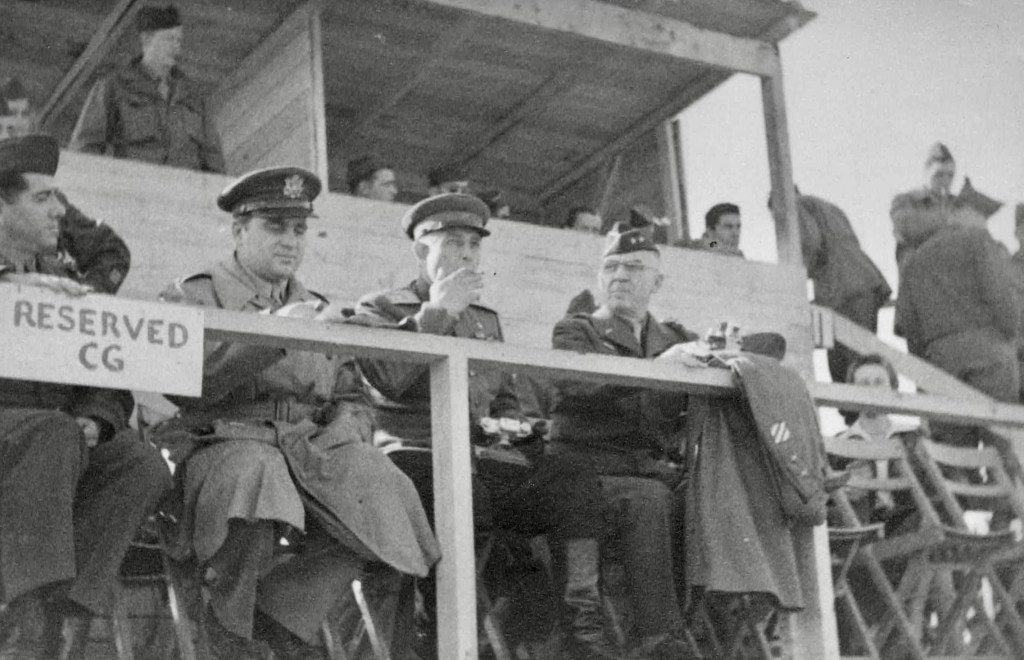

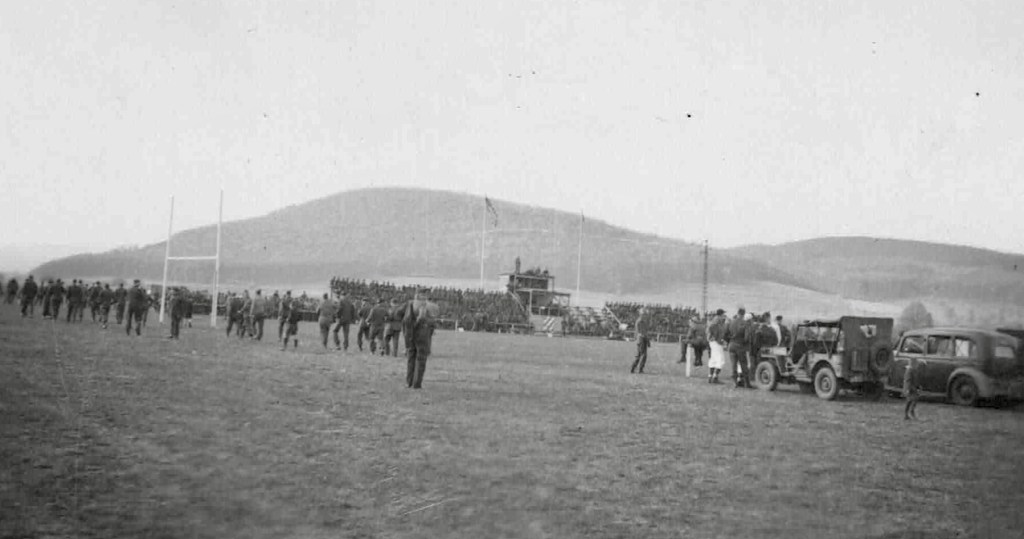

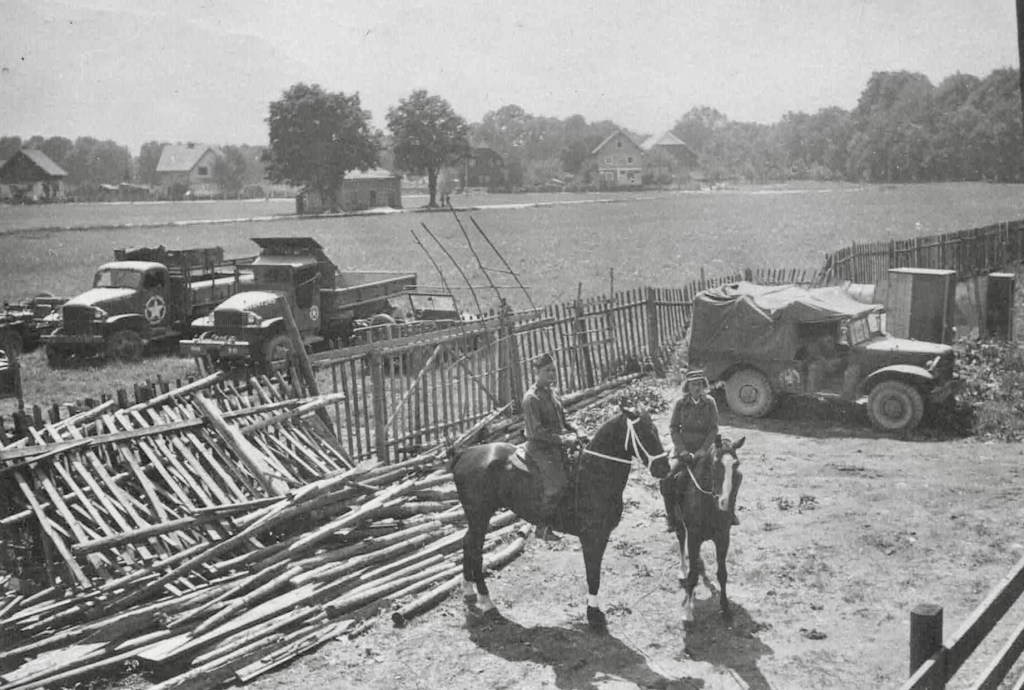

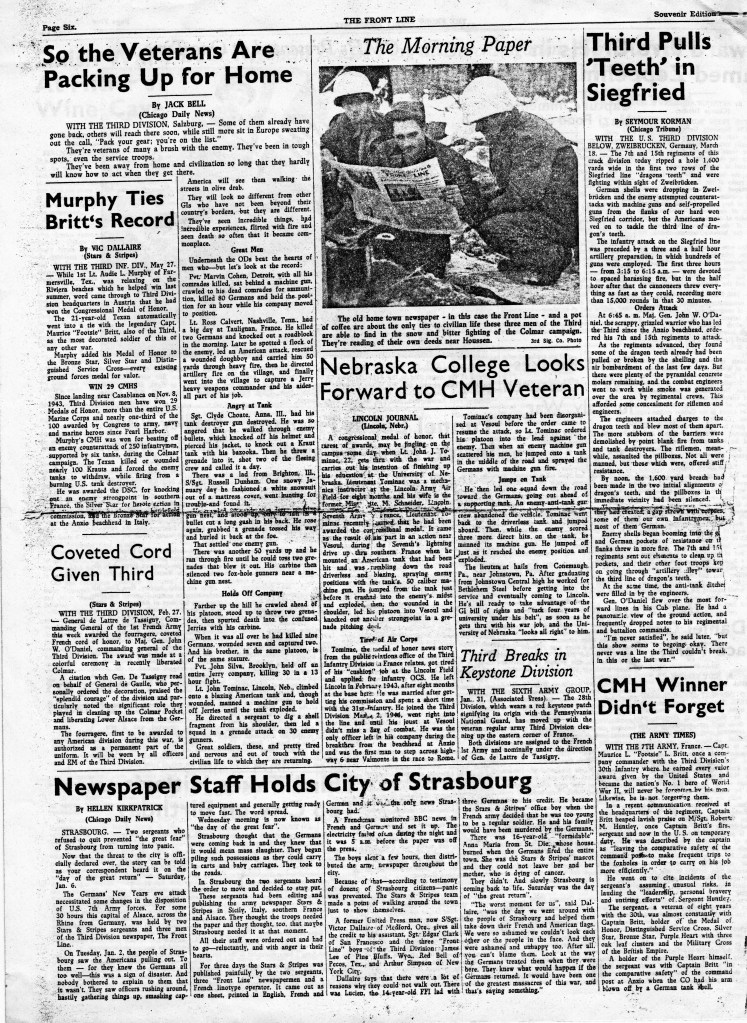

Don’t throw this away! admonishes the Front Line newspaper of their post-war special edition. Flo didn’t throw it away. She saved it and tucked it into her album. The issue consists entirely of stories which appeared in the big and little dailies of the nation about the Third Division.

From the introduction: “During the rush of battle few men were able to get a hold of a newspaper published in the states, much less take time to read it thoroughly….Hence, this special edition.

“We hope you hang on to your copy as the supply is limited to one per man. If you want to send it home, go ahead. All the material in it was censored by Sixth Army Group censors before it could appear in the home town papers.”

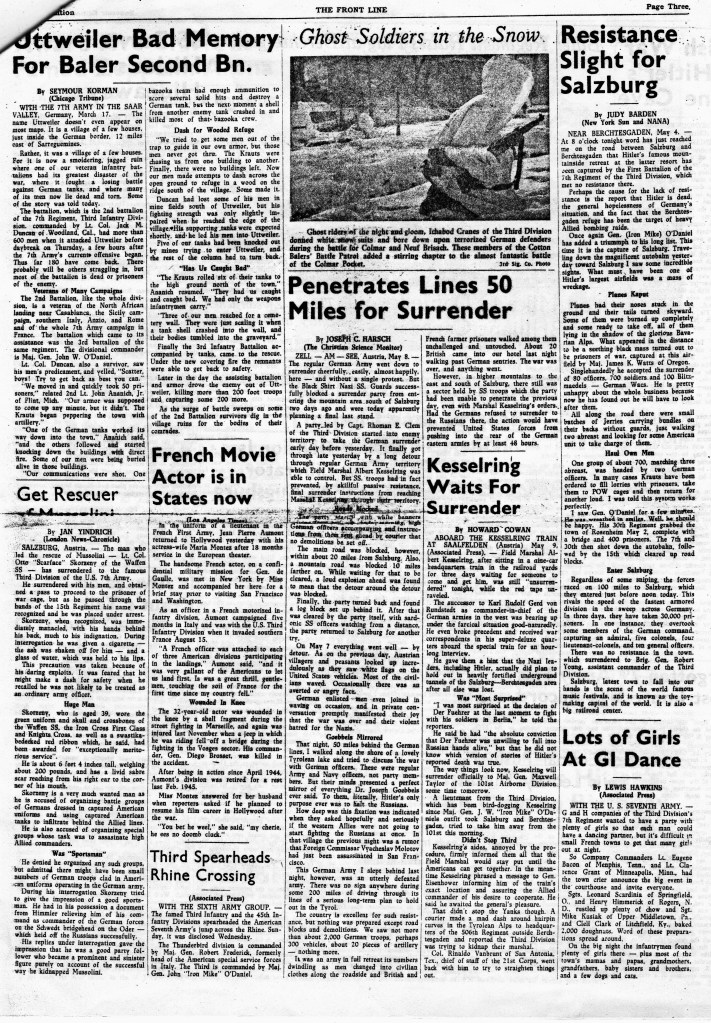

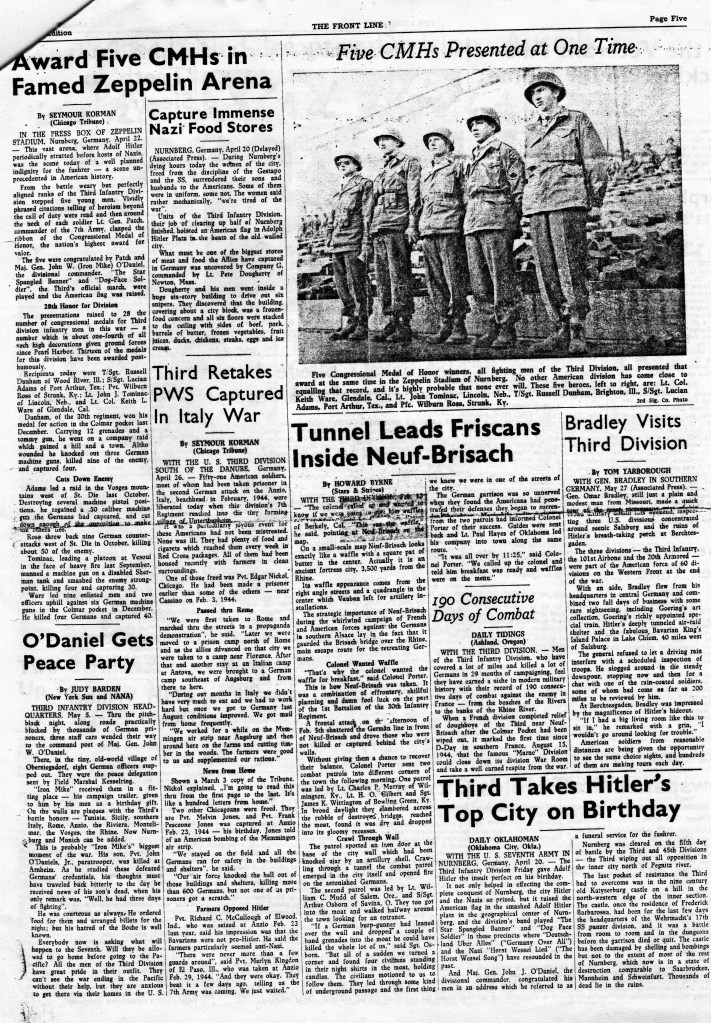

The Front Line is the official newspaper of the Third Infantry Division. In the interest of archiving, I’m posting the whole six-page paper. You can read it by pinching out the image.

Ch. 101: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/03/07/a-sweet-love-poem-to-a-flyer/