Murphy gets hit, Flo takes a break

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 39

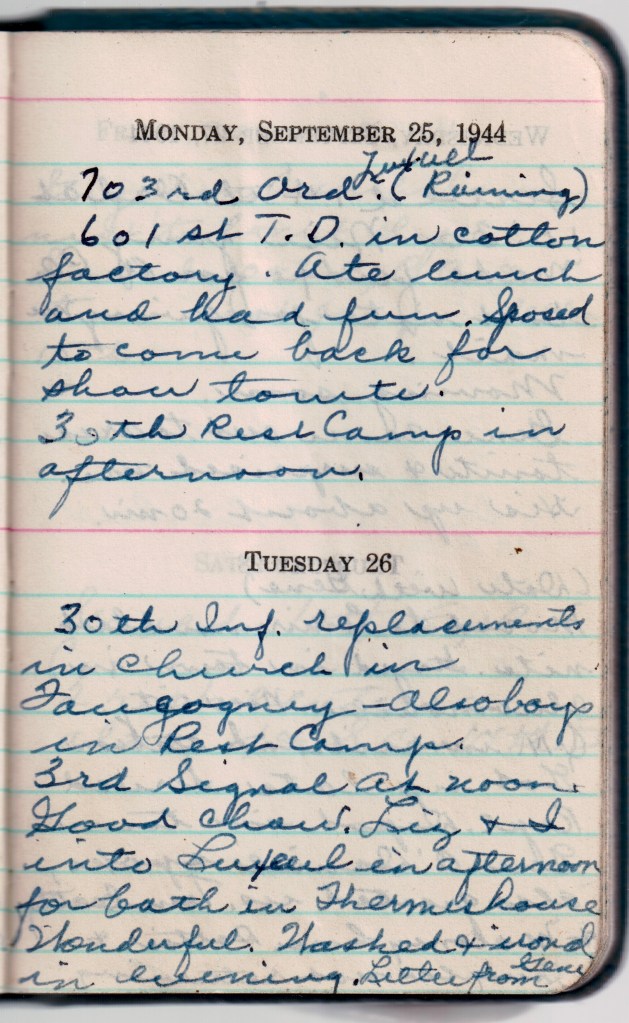

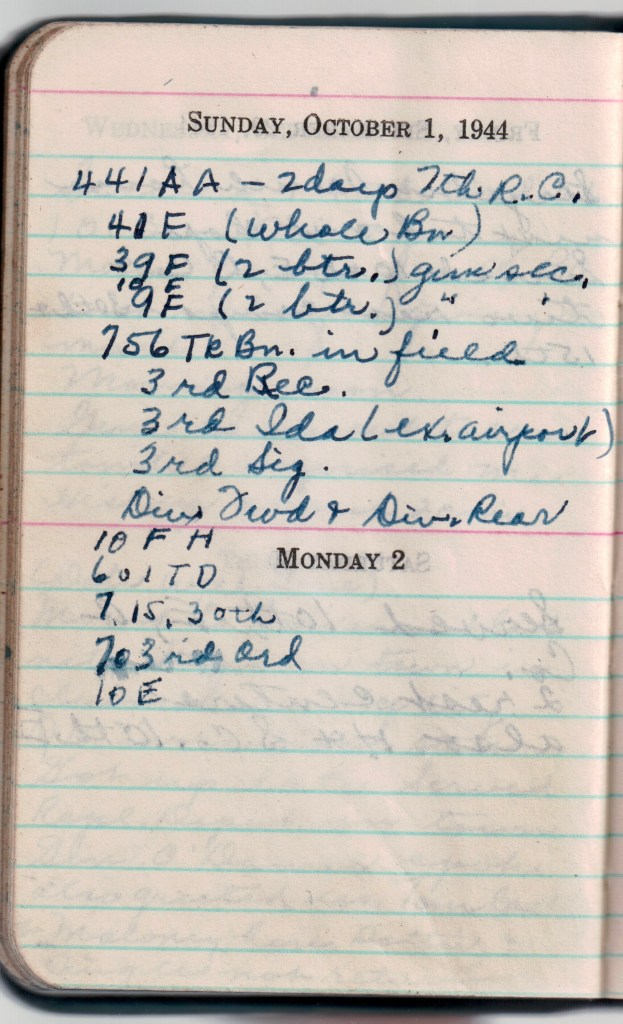

October 1944. Flo’s diary is blank from October 2 to October 7, 1944. There’s no way to know what happened during that time, but there are clues. My cousin told me that at some point during the war Flo went to Paris for an abortion. I wrote about it here: https://mollymartin.blog/2022/04/16/solving-a-wwii-era-mystery/. The city had been liberated in late August and it would have been possible for Flo to travel there and back in five days. Flo stayed in touch with her sister, Eve, who was serving as an Army nurse in a Paris hospital. Eve told me that Flo had also suffered a miscarriage while hauling heavy equipment. Flo never wrote about any of it in her diary, and she never spoke of it later. But whatever happened during that week, it was serious enough to stop her from writing altogether.

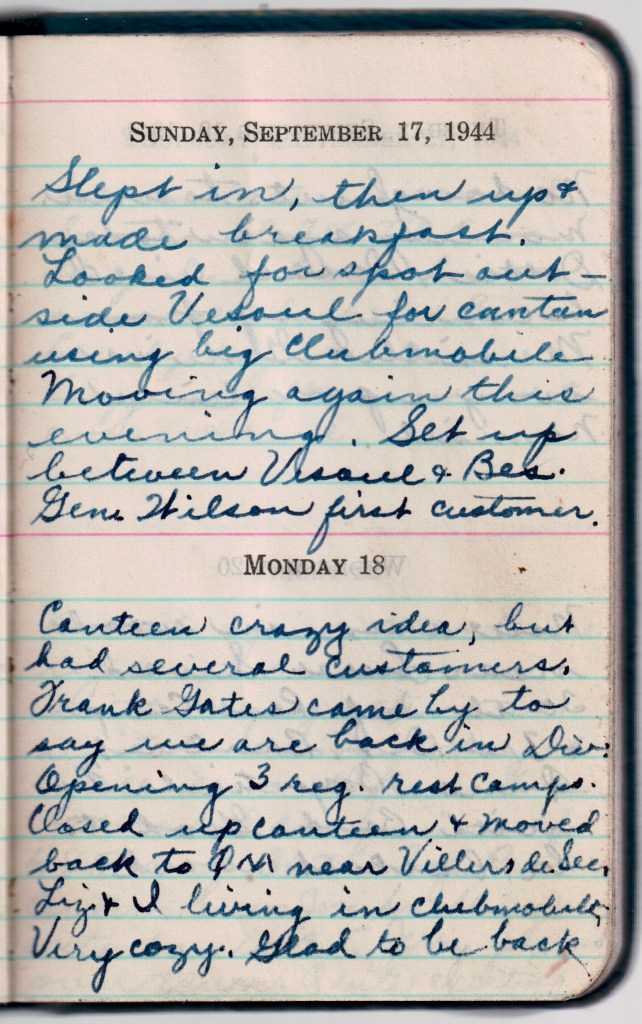

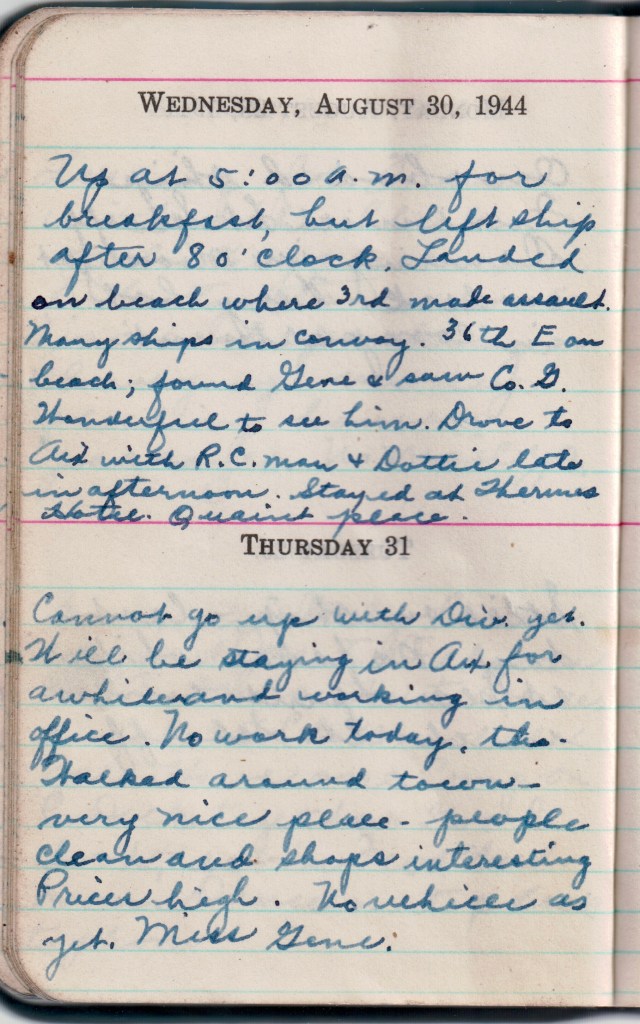

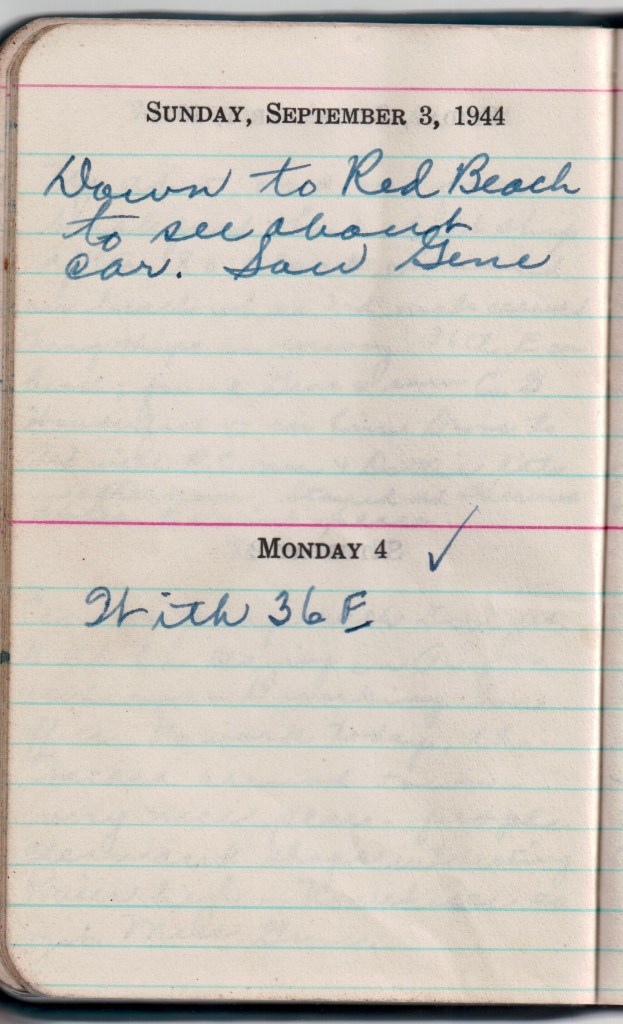

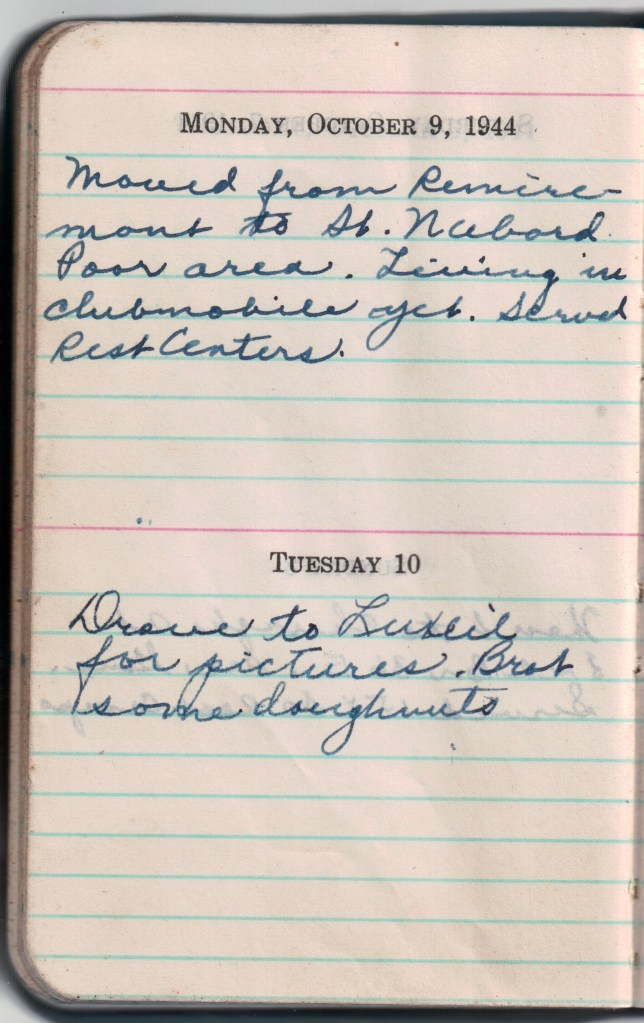

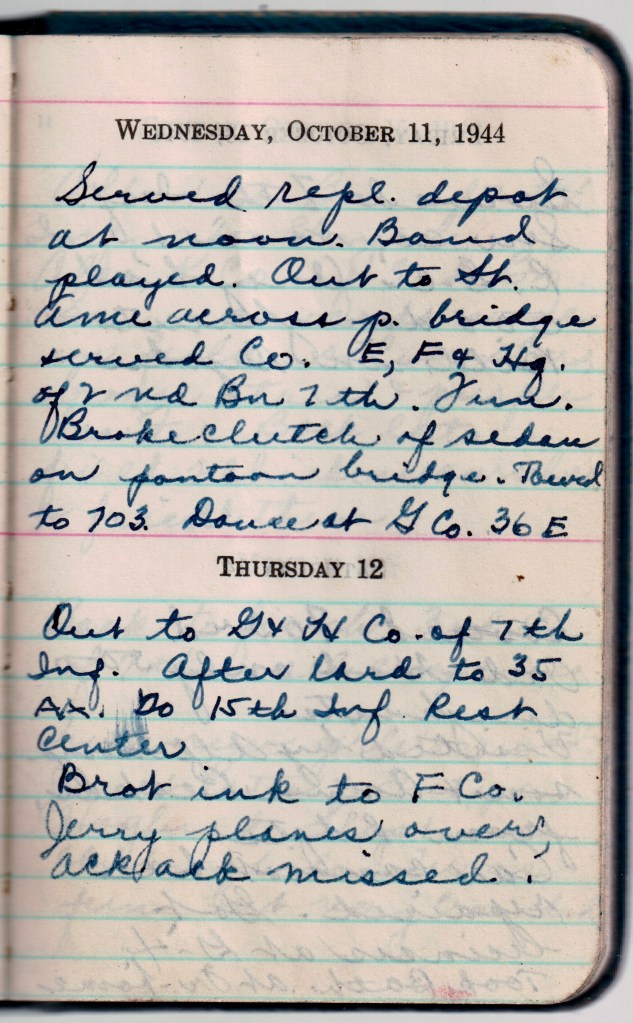

Flo’s diary (pinch out to read)

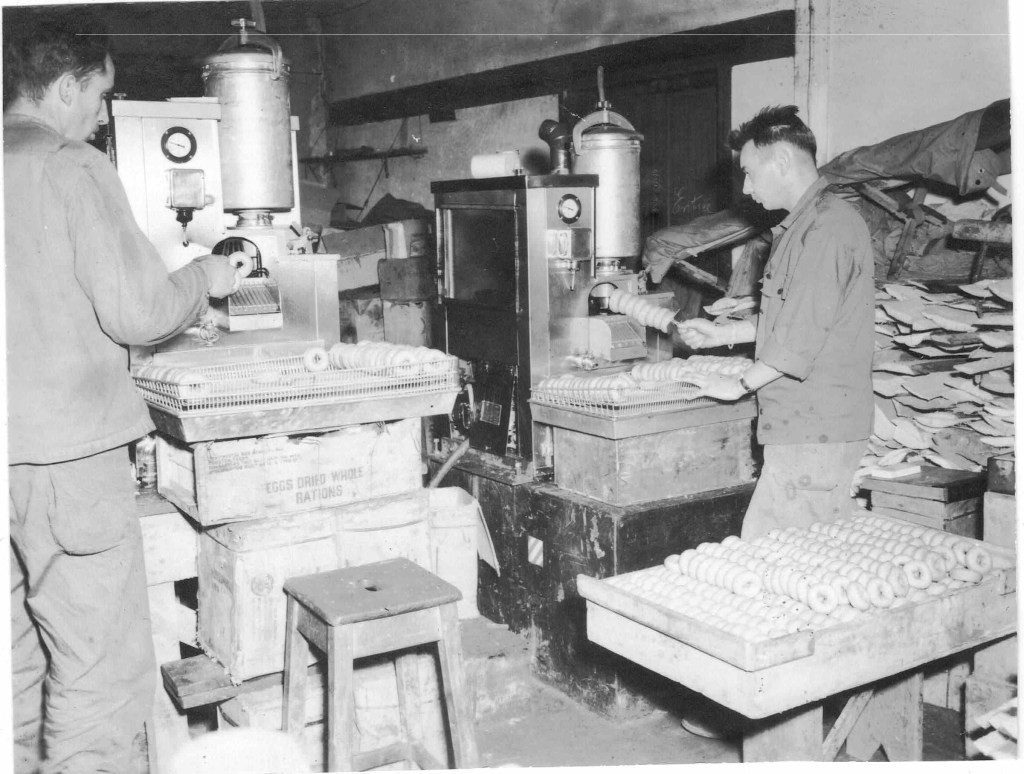

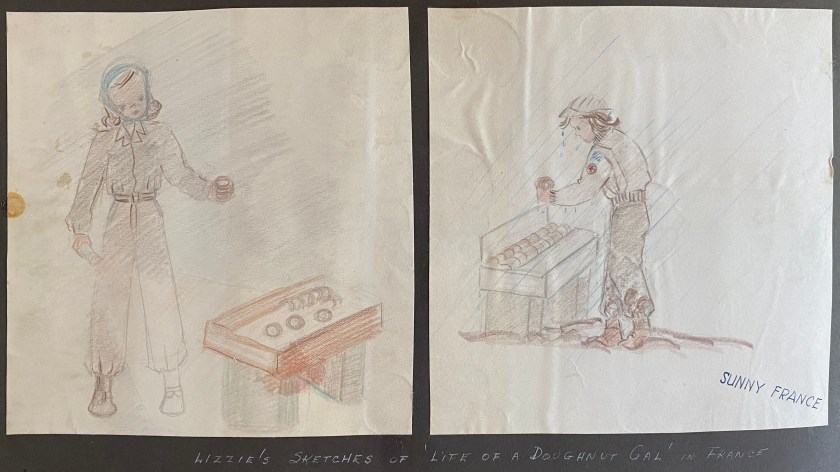

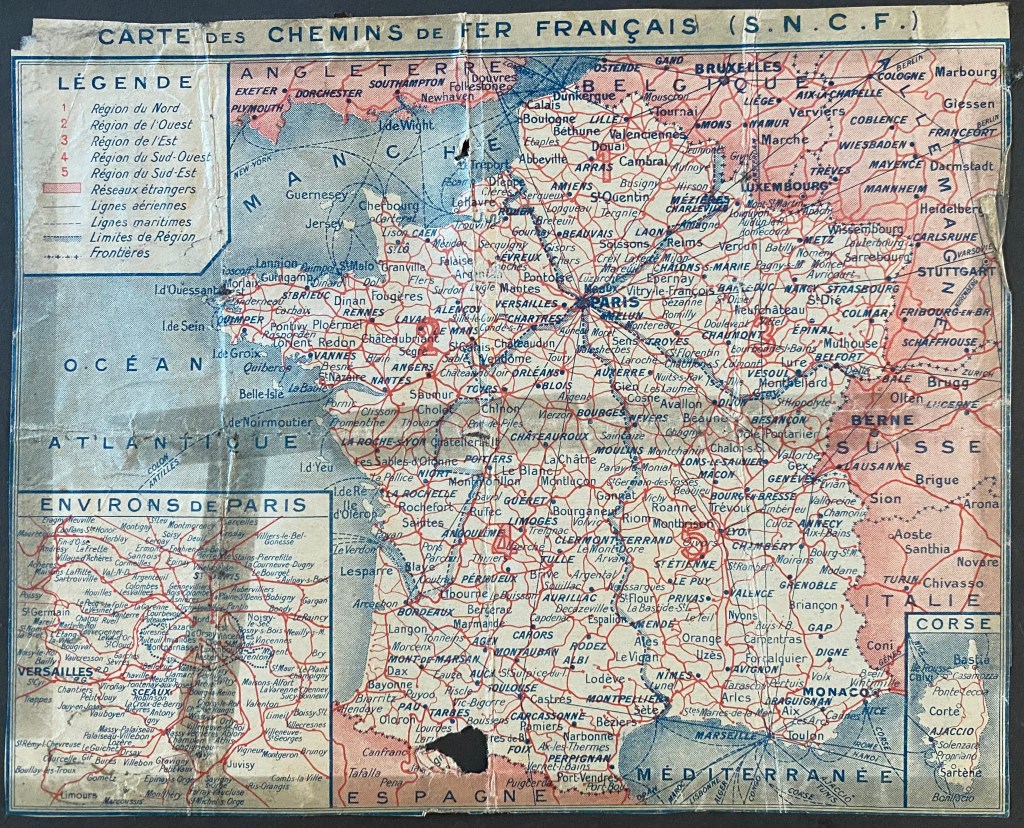

By October 8, Flo and Liz were back in action, serving hundreds of donuts to American troops every day. They had moved from Remiremont to nearby Saint-Nabord, a grim, war-torn area where they now lived in their clubmobile. One day they drove to Luxeuil for photos. Another day they served the replacement depot while a military band played. And then they bounced across a pontoon bridge into Saint-Amé, until their battered old sedan gave out. The clutch snapped halfway over the bridge and couldn’t be repaired.

During this time, they served the 15th Infantry—Audie Murphy’s unit—a couple of times. The men were quiet, polite, exhausted. After some hard battles, the 15th was finally getting a little rest. But Murphy was not among them. He had been wounded in the fight for Cleurie Quarry. At the aid station, he learned that nearly his whole platoon had been wiped out the night before. Because of the rain and mud, the wounded men could not be evacuated for three days. At the hospital Murphy learned gangrene had resulted. He would be out of commission until January.

In breaks from battle, the army handed out medals. The Third Division took home more than any other. This would be Murphy’s third purple heart.

Flo was able to see her fiancé Gene occasionally, as his unit, the 36th combat engineers, was stationed nearby. They met for church, a dance and meals at his camp. They planned to marry by Christmas and he had ordered rings for them.

On October 1, Flo sent a formal request to William Stevenson at Red Cross headquarters for permission to marry Gene. The form letter says,

“If permission is granted, it will be predicated on the sole understanding that it will in no way interfere with my responsibilities to Red Cross and that I will carry on my obligation to the organization. I shall gladly carry out my duties wherever the organization may ask me to serve and I will not request transfers within the theater or elsewhere because of my desire to be with or near Capt. Gustafson.”

In her accompanying letter, Flo had again managed to put her writing skill into practice. Whatever she wrote convinced the ARC. She received permission to marry in a warm letter from Eleanor “Elly” Parker, Director of Staff Welfare, dated October 23.

She wrote, “Thanks very much for your nice letter and I feel much more comfy issuing your marriage approval after having your explanation of exactly what is happening….You sound well surrounded by friends and family in France and I am glad you enjoy being there….I imagine that you are terribly busy and very hard at work under pretty trying cricumstances….

Apparently Flo also had asked about getting some shoes after her nice shoes were stolen in Italy. But Elly Parker wrote that all they have at the PX are “regular black Red Cross shoes.” Not exactly what Flo, a lifelong shoe queen, had in mind.

On October 12, German planes flew overhead. Everyone looked up at the roar, held their breath as the anti-aircraft fire opened up—and missed.