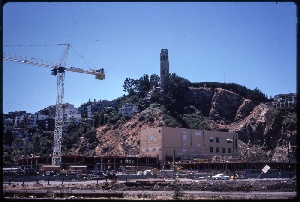

Telegraph Hill – 1974

By Eric Johnson

I worked for Plant Bros. of San Francisco in the early Seventies. After a probation period, they sent me to a jobsite that had just begun, in the shadow of Telegraph Hill, right by the waterfront. They had to completely overhaul an old grain warehouse and convert it into an upscale office building. The location was great – you could walk at lunch-break over to the wharves, or just sit in a vacant lot and look at the Bay. And the building was interesting, especially as we began to mine our way into it. It was a remnant of the industrial past of San Francisco’s waterfront, a brick five-story warehouse with rugged interiors. We had to earthquake-proof it, tear up flooring, destroy the old freight elevator shaft, and then frame up the new sets of offices. The flooring had been laid when mahogany was cheap, so we were cutting through two tongue-and-groove, inch-thick mahogany floor layers. We burned out blade after blade of our skilsaws and spent weeks with crowbars ripping out and dumpstering the wood. Then re-flooring it with heavy plywood.

This first month was not really carpentry, but I liked it. For one thing, I had an apprentice assigned to me – which was my first time having that responsibility. He was a young Chinese guy who I liked immediately. Eugene knew he was a token of integration for the union – there were less than ten Asian carpenters, and the local was under pressure from all minorities to open up. Eugene and I were attuned in the political culture of San Francisco in the early Seventies and we also both knew how to work with alacrity. Things got even more interesting when they hired a Mexican-American woman named Inez Garcia. She was only the second woman in the union’s history. I had worked with the other, at the General Hospital job. They had assigned her to simply push in all the snap-ties on all the forms, thus earning her the name “snap-tie Mary”. There was a quarrel in the union to get her boss to actually let her learn the trade.

Now Inez was in that position, but it was more promising. The foreman was civil to her and we formed-up a little team, with Eugene and I and Inez and an older Italian guy named Ron. I was given the lead responsibility of cutting a big trapezoidal hole through all five floors for the new open stairway in the center of the building. The foreman and I studied the blueprint, devising a way to place that trapezoid correctly in reference to the walls – then I explained it all and assigned us to different duties. It went ahead really well at first. The challenge of the cutting was apparent and the two young recruits felt that I was teaching them things. We had lively lunch breaks, and I started looking forward to coming in to work.

After the layout was agreed on, we built walls along those lines from the floor to ceiling, tightly wedged so that the weight of the floor above would be supported when we cut the shape out of it. We finished it late one day, and the next morning we were going to start the cut on the second floor. I woke up early with a clutch of anxiety. Something was wrong, I was sure of it. I got to work early and studied the blueprint, stared at the lines, the walls…and suddenly knew what it was. We had built one of the walls on the wrong side of our chalk line; it would be the width of the two-by-six too small! Oh shit, this will look bad. Good that I’d caught it before we cut through above, but… here we had this big twelve-foot-high wall we had to tear down. Luck was with me, as the foreman had to be at another job for the first hour. I told the others what we’d done, and they gravely considered it. I told them we had a slim chance to avoid detection if we all four went at this furiously; removing nails, sledge-hammering the walls over, adding some pieces to fill in, plumbing-and-lining it again…and re-nailing. So that’s what we did, everyone working twice as fast as usual… and just had the wall in place and nailed when the foreman came in. I was already upstairs laying out the cuts. He waved happily and we were home free.

Those cuts were not simple either. Once we had lines snapped and were dead certain of them, we had to Skil saw through the double layers of mahogany. Then we confronted the huge joists, rough 4 x 12 timbers, some of them doubled-up. The foreman got us a chainsaw, and after carefully extending the lines down over the angles of the joists, I started lopping them off, confident from my memory of doing the same thing on the roof at the Unitarian Church. This all went very well, and we progressed upward the remaining four landings, making the same cut each time. Inez and I became good friends, Eugene was becoming the job wit, and I was beginning to enjoy my own leadership. It was interesting to see the way what they wanted to have happen socially was allowing me to be more who I was. Not a leader with commanding certainty, but someone who would let others see my process, my confusions. I could ask for help, and even make things fun.

The new elevator was going to be hydraulic, and it needed a hole as deep as the building was tall – for the piston to recede down into it when the elevator was on the ground floor. So there was a big drilling rig at the building’s edge, boring a four-foot-wide hole…sixty feet deep. At thirty feet they hit some rubble. Pieces of the old waterfront fill. Then there was stone. The auger couldn’t penetrate it and they brought in a specialist.

Mario was a Latino guy who was like a deep-sea diver. He was to be lowered down the hole with a jackhammer so he could break up the layer of stone. We saw him getting ready early the first morning and Inez asked him what the hell he was going to do? It looked strange, the special winch they had for lowering him down, the cradle of canvas straps, the jackhammer hose, his oxygen mask. He explained the whole thing as if it were routine, then says he never feels claustrophobic because he smokes a joint first. I had trouble understanding that part. If I smoked a joint first, the last place in creation I’d want to be, would be thirty feet down a shaft too narrow to move around in. But he assured us it was the only way he could stay calm and focus on the simple task of it. I said, what if you space out and don’t realize you’re not getting enough air? He said he had a regular code of tugs on the rope and that they would frequently tug at him for response. Jesus. We watched him go down…and then felt the vibrations of the hammer. He worked about a half hour and then they pulled him up, covered with dust. He laughed at us, drank some water, and went back down again. We talked about it all day, how…bizarre it was. Mario was either a great hero …or a chump who would be dead tomorrow.

He didn’t die, but he did share his joint with Inez, Gene & me the next morning. Two tokes was enough to make me want to go off wandering along the waterfront to study wave patterns and old fishermen. Gene and Inez were used to smoking more, and able to buoy me up those first few hours. The work we were doing was hilarious for a while. Gene started giggling at the stack of fresh plywood. He said there were flies on it, it was ridiculous somehow. I got a can of spray paint and wrote “ FLY WOOD” on it huge. We were hysterical. “Inez! Go get us a sheet of flywood!” She exploded when she saw it. What fun! But, but, … I was the lead man, I had to fight through this, I had to keep working and, like Mario, find somehow the even keel of bemusement yet purpose. It wasn’t easy and I decided next day to pass on the offered joint. In fact it was fifteen years before I ever tried that again, and then almost fell off a roof. Not all of us are as talented as Mario. At the end of the week we had decided that in truth he was a hero of the first order. He had broken through several feet of hard rock and the auger went back at it. Mario shook hands with a grin, and rode off into the fog.

Our foreman was transferred, and a new guy brought in. At first we liked him all right. He seemed comfortable with the two young minority apprentices, and came over to yak with us often. But after a week, he started being too comfortable…with Inez. He kept her after work one day with a contrived duty, and a few days later switched her to a solo task, which broke up our team. She was given the job of boring all the holes in the brick wall on every floor, that would allow the earthquake bolts to be set in from floor structure to exterior brick. There were hundreds of these to do, and one had to get down on knees or recline positions to hold the impact drill with any authority. It was…the worst job. Each of us had done it for a few hours on other days, and at first we thought, well, someone has to do it, apprentices often get this kind of grunge work. But then it went on the next day, and the next. Inez came up to me after work and said we had to talk. We went for coffee and she told me that Jim had propositioned her a couple of days back…and she had turned him down. He was pissed and told her he would make life miserable for her unless she ‘dated’ him.

So that explained the sentence of hard labor. Inez was furious, but she felt she had no grounds for saying she shouldn’t have to do the job. Inez was really a rugged, working-class woman. The last thing she wanted was to be perceived as whining about physical labor. In fact, she was as strong as me, a formidable person – who also was not a bit afraid of Jim physically. In fact, she was bigger than him. That made it even more disgusting. He was unable to force her or convince her or attract her. The raw power of the paycheck was what he had. When she had complained that he was treating her unfairly with the hole-drilling, he’d simply said, “Okay; then date me or you’re fired!”

I advised her to go to the union in the morning before work. Apprentices are supposed to be instructed, for one thing. And then of course there’s the sexual harassment, a legitimate and potentially scandalous thing for the company. I told her who to see, the most reliable of the business agents, and asked if she wanted me to come with her. She said no, she wanted to be able to carry herself as a stand-up member of the local, not dependent on anyone.

Next day she was gone. I called her that night and she said the union rep had taken her side with integrity and had called the company. They agreed to transfer her to another jobsite and make sure she was treated fairly if there was no threat of a lawsuit. Inez had agreed to this, but we both felt depressed. I felt I had to apologize for the whole backward mob of jerks that populate construction work. It was as if she had been a lantern in a cave, revealing our stupid scuttling ways. Ugh. She told me to drop that rhetorical bullshit, that the only thing that depressed her about it was that she would miss all of us. It was just one jerk, really… but one spoiled everything.

Jim was still foreman on that job for another two weeks – while we frosted him. Then, out of the blue, the union announced that contract negotiations had broken down and there would be a city-wide strike. When that all blew over, I found another job. Plant Bros. was tainted for me.

Eric Johnson is a printer who writes stories about his work as a carpenter in San Francisco.