October 24, 1983

Pacific Heights Woman Strangled

I see the headline, then discover to my horror the woman was Sue Lawrence, a fellow electrician. Back home with Sandy gone to class and after a day full of questions from men at work I’m terrified at the prospect of my own victimization. That “nude body face down on the bed” could be mine. What if, as in some Agatha Christie plot, the murderer is going after all the female electricians in the city? Will I be next? In the shower, a most vulnerable state especially with a head full of shampoo and eyes closed, I imagine Ruth pounding on my door to be him. Panic strikes. I manage to wash shaking limbs.

***

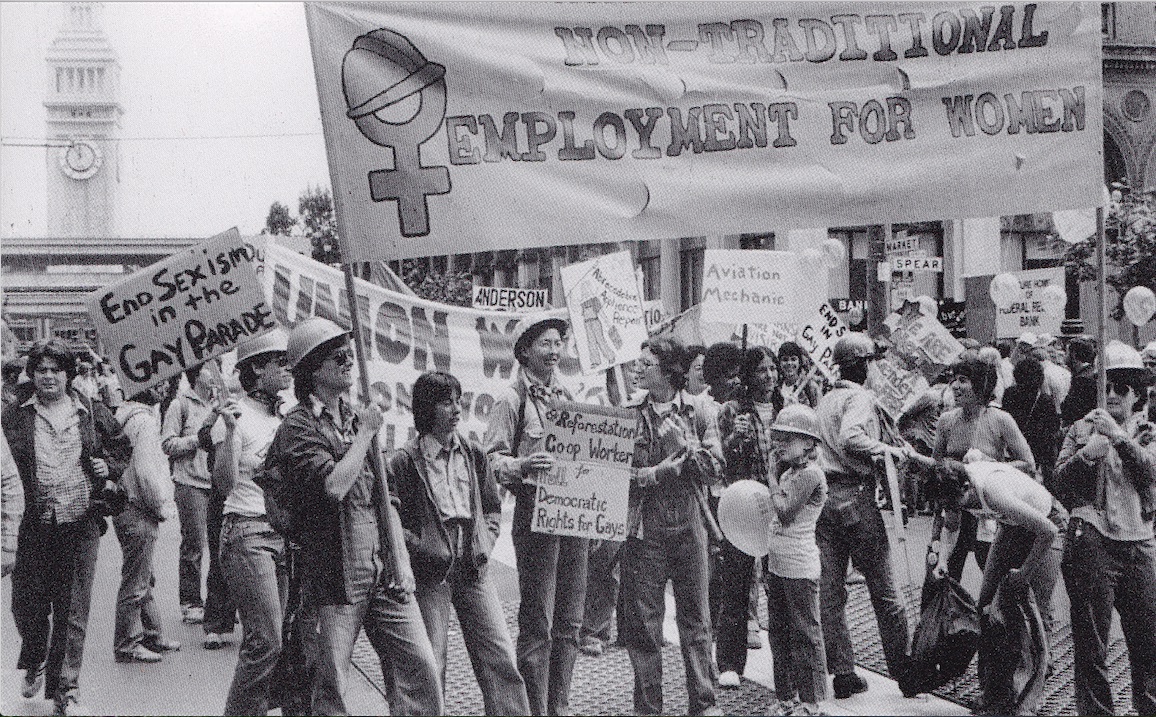

I was not the only one terrified by Sue’s murder. Other female electricians in the city had the same thought. There were so few of us since union apprenticeship programs had just recently opened their doors to women after years of pressure and lawsuits. We were in the minority. We were not welcomed. We were scorned. We already felt vulnerable as women in an all-male work environment. Now this murder had us all freaked out.

Sue’s memorial was held at the Episcopal church just off Diamond Heights Blvd. We met Sue’s parents and heard a minister recite a rote speech, but we learned very little more about Sue than we already knew, which was not much.

Afterward we repaired to Yet Wah, a Chinese restaurant on the upper floor of the shopping center across the street. There the women electricians of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 6 gathered to celebrate the life of our sister. We were joined by two or three tradeswomen from other crafts.

We had been working on construction sites that day but, as construction workers say to each other outside of work, we cleaned up pretty good. You couldn’t look at us and tell that we were electricians. I wore my only “good” outfit, a sports jacket with sleeves rolled up bought at Community Thrift, the gay secondhand store on Valencia Street. Paired with black jeans and a white shirt I could go anywhere.

My roommate Sandy was a fashion plate and took this opportunity to wear a dress, a fifties number with a pencil skirt. She had a tiny waist and large butt so she had trouble finding work clothes that fit. Manufacturers didn’t make work clothes for women. Away from work Sandy took refuge in skirts. She had always wanted to work in the fashion industry but couldn’t find a job there. She felt she didn’t fit in construction, but the money was a powerful incentive.

Others dressed in black funeral attire.

“Sharp,” said Alice when she bumped into Dale, who was wearing a suit and tie. “Very avant garde.”

Ten of us were seated around a big round table with a lazy susan in the middle for family style serving. As big plates of Gung Pao chicken and mu shu pork revolved, we collectively decompressed.

I had worked out of the Local 6 hall for a couple of years, but I had never encountered any of my sisters on the job. We were isolated and alone when at work. Our active support group of Local 6 women gathered monthly to share stories and to support each other. The sisters’ gatherings helped us feel not so alone. We had been pushing for a women’s caucus in our union local, a caucus with the union’s endorsement.

“So I got a cease and desist letter from the union,” said Sandy, whose thick Boston accent left us westerners chuckling. “They said if we don’t stop meeting they will kick us out. We are not an authorized caucus, and there’s no easy way for us to get authorized.”

“Are they serious?” said Joanne. “Would they really do that?”

The business manager kept a tight rein on the local. We heard those who attempted to challenge his leadership had been blacklisted, but it was hard to imagine the local disenfranchising its handful of female members. We had only just made our way in. At that time there were fewer than ten of us in the union local. We decided to keep meeting. But it was a clear message—the union was not our ally and we should not seek support there.

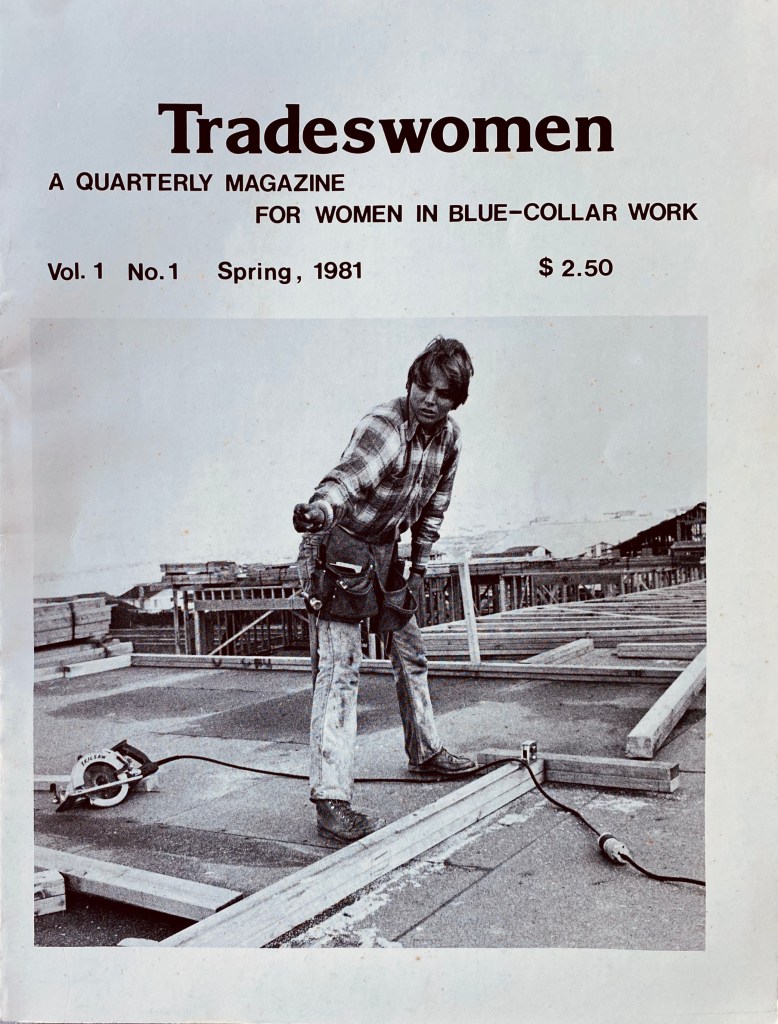

Sue Lawrence had entered the IBEW apprenticeship when she was only 18. She was about to graduate from the four-year program when she was raped and murdered by the stranger who broke into her parents’ house.

I knew Sue only from the sisters’ meetings. She didn’t talk much. I didn’t even remember having a conversation with her.

“She was weird,” said Dale. “A newspaper reporter called and asked about Sue. I didn’t know what to say. I think she was suffering from manic depression. But, hey, we all know you have to be a little bit crazy to go into the trades as a woman.”

Nods around the table. We all felt a little bit crazy.

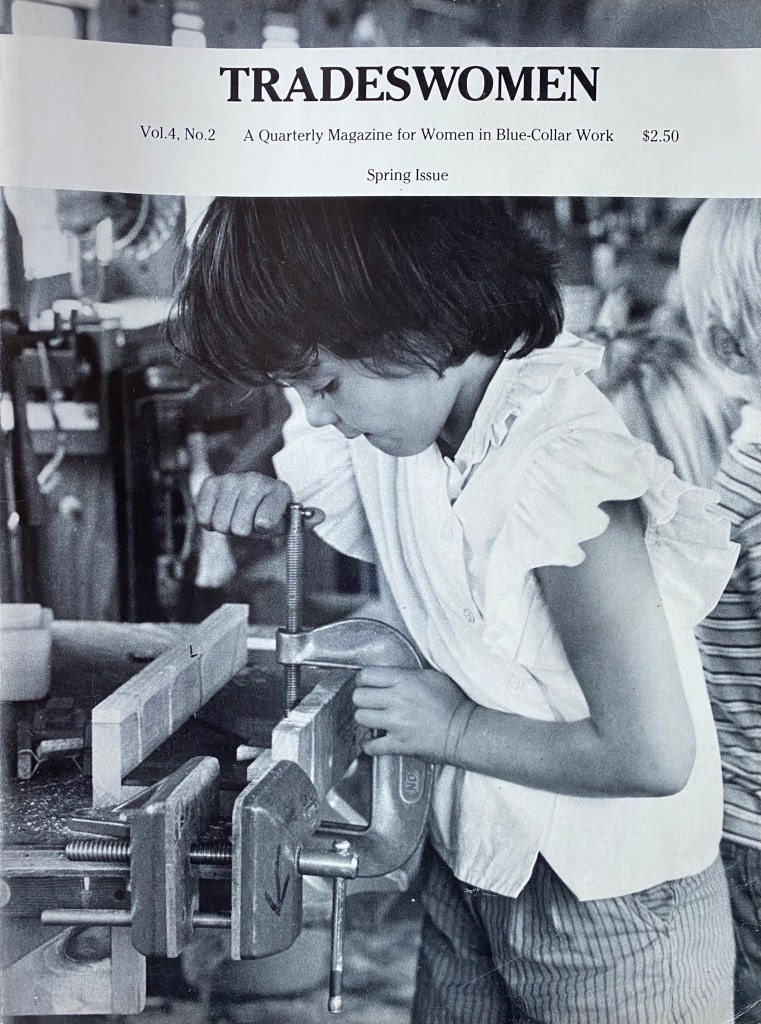

“I know she struggled during her apprenticeship,” said Jan. “You know she started right out of high school. That’s rough. Younger women get more harassment. But she made it through and she was just about to turn out as a journeywoman.”

“The last project she worked on was that big housing complex at the ocean where Playland at the Beach used to be,” said Dolores. “She was the only woman working there.”

“I think she was struggling with her sexuality,” said Alice.

Sue was an enigma to all of us. Had any of us been there to support her? Maybe not to the extent we should have been.

Sue lived with her parents in the house she had grown up in on Green Street. I had driven by it just to see where she came from. It was a rich part of town that none of us frequented. Her parents had some money. Maybe Sue hadn’t fit into the box prepared for her. She was an unlikely electrician, but I knew several of them—women whose parents were doctors and who rebelled against parental expectations by going into construction.

Tradeswomen can’t get together without talking about discrimination and harassment we experience on the job. No one else really understands or wants to listen to our complaints.

“Can I be honest,” said Lynn. “Since Sue was murdered I haven’t slept well. I’m scared. Was Sue attacked because she was an electrician? Are we at risk of being attacked?”

We looked at each other. I hadn’t slept well either. We didn’t know anything about Sue’s killer. What was his motive?

Jennifer told us how she had been attacked and raped in her own house the year before. Sue’s death had been hard on her. The only female on her job, she couldn’t shake the thought that her coworkers might be abusers and rapists. She had stayed off the job and was terrified to go back to work where she felt profoundly unsafe. She confessed that she didn’t know how much longer she could stay in the apprenticeship.

“Maybe I have PTSD or something,” she said. “Whenever I think about going back to work I get the cold sweats. I’m starting to think I just can’t go back.”

Pat, who had started in one of the first apprenticeship classes of Local 6 women in 1978, complained about being dyke baited.

“One of the guys called me a bulldagger the other day,” she bellowed. Pat had a mouth on her. Maybe that’s how she survived.

Pat was married to a man and they had two young children. I had seen a picture of her at her graduation from the apprenticeship. She was standing next to her tuxedoed husband and dressed in a fancy gown made of filmy blue material like women might have worn to any other graduation ceremony. Even in that gown Pat looked like the butchest bull dyke we knew. She kept her hair short and had a stocky body. On the job in her work clothes and tool belt Pat radiated authority. How sad to have to put up with dyke baiting when you’re not even a dyke!

“Pat should officially be an honorary dyke,” I said. “She gets dyke baited just like us lesbians, maybe even more.”

And we all agreed. Dale stood and, pretending to wield a magic sword, touched Pat on both shoulders and declared, “Pat, I now dub you an honorary dyke. Your ID card will be mailed to you.”

And it was then that I truly understood that dyke baiting was not as much about lesbians as it was about ensuring that we all meet certain stereotypes of what men think women should look and act like. Dyke baiting on the job affected all of us, gay and straight.

The conversation turned to tradeswomen organizing. We had been making an effort to hire childcare for our meetings and conferences but it was a struggle. We had no budget so we resorted to passing the hat to hire a childcare worker. The dearth of childcare meant that some of our parent members had to bring their kids to meetings or stay home. The only woman at the table with kids, Pat supported a childcare initiative.

“But you’ve got a husband,” said Alice. “Why can’t he stay with the kids.”

“Yeah I’m married, but you’ve got a partner too,” countered Pat. “This is just discrimination against mothers. Do you want us in the group or not?”

Samantha, sitting across the table, sent me a look. We had been flirting for weeks. She was so damn cute, curly dark hair framing a round face, a small woman with a muscled frame. We had been lifting weights together at the Women’s Training Center on Market Street.

It was a period in my life when attractions proliferated and sometimes the attraction could not be ignored. Sam’s look required follow up. She politely excused herself from the table and I waited a moment before heading in the direction of the women’s room.

The bathroom had two stalls. I entered the one nearest the wall. Sam was close behind, gliding in and locking the door. Smiling, I caressed her firm delts. I knew how much she could bench. She was so hot. I gently pressed her back up against the door and lowered my head slightly. The kiss—long and soft—weakened my knees.

Others crowded into the bathroom.

“Hey, can I have some of that too,” called Dale, looking under the door at our four feet.

Busted!

We walked out with sheepish grins to a line of sister construction workers waiting for the stall.

“Get a room,” someone yelled.

They were taunting us but they were all laughing. And then we were laughing too, a practiced survival tactic.

***

October 27, 1983

Sue’s memorial service and dinner with the women electricians afterward inspires me to see these women as my sisters in struggle. I feel our collective rage and hurt and vulnerability. When I tell them I imagine a plot against women electricians, all admit the same horrible fantasy. Jennifer who survived being raped and strangled in her own house last year is hardest hit but others tell of their terror at staying alone at home.

***

Though I conflate these events in my mind, it wouldn’t be until six years later that we would witness a mass killing of women who deigned to study what had been “men’s work.” On December 6, 1989, Marc Lepine entered a mechanical engineering class at the Ecole Polytechnique in Montreal and separated the women, telling the men to leave the room. He said he was “fighting feminism” and opened fire. He shot at all nine women in the room, killing six. He then moved through corridors, the cafeteria, and another classroom, targeting women. He slaughtered eight more before turning the gun on himself.

That guy had a motive.