Audie Murphy recalled landing on French soil

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 24

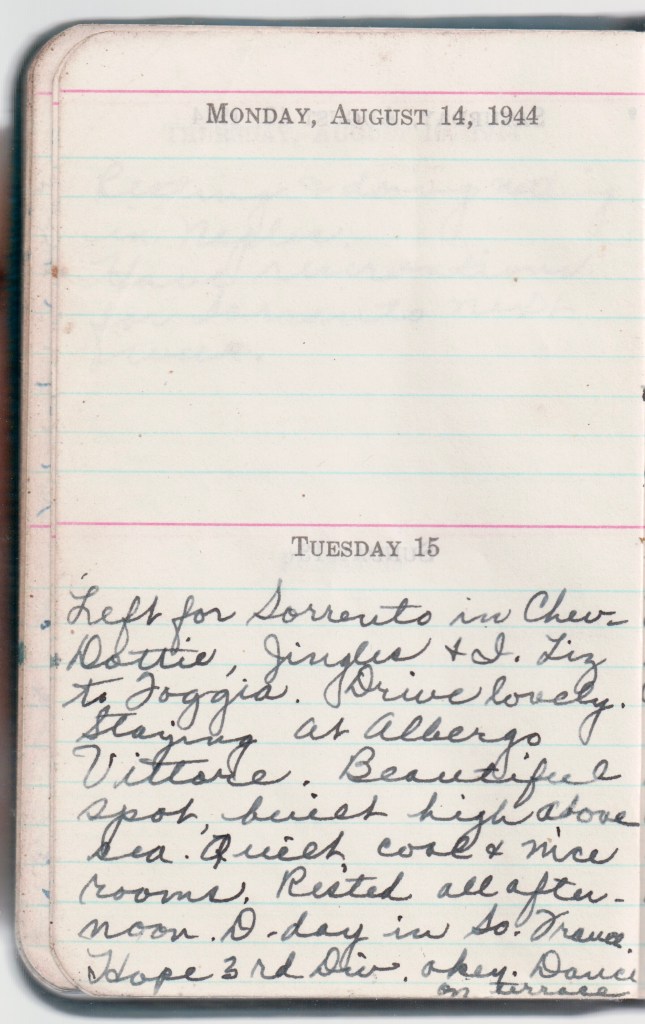

August 15, 1944. From Murphy’s autobiography To Hell and Back:

Audie Murphy later described the landing in southern France in his autobiography To Hell and Back. He recalled that, technically, the operation was considered perfect. The assault had been calculated to the smallest detail, every movement coordinated so that the effort unfolded with the smooth precision of a machine.

Compared to earlier invasions, resistance here was light. Weeks before, Allied forces had already broken out of Normandy and were cutting through northern France like a flood bursting through a levee. On the eastern front, the Russians were hammering the German armies. Overhead, American bombers were grinding German cities to rubble. Murphy likened Germany’s situation to that of a man hiding in a stolen house, frantically running between front and back doors as justice pounded from both sides—only to realize too late that another force was now rising up through the cellar. His regiment, Murphy observed, was that third force.

Yet the men in the landing craft knew nothing of this sweeping strategic picture. They saw only the edge of the boat, the immediate shoreline, and the moment that lay before them. Their first objective was a narrow, harmless-looking strip of sand called “Yellow Beach.” It was early morning in mid-August; a thin mist hovered above the flat fields beyond the shore, and beyond that, quiet green hills rose inland.

The bay between St. Tropez and Cavalaire was crowded with the familiar pattern of an amphibious assault. Battleships had already given the coastline a thorough pounding and now drifted silently in the background. Rocket craft followed, launching volleys that hissed through the air like schools of strange metallic fish, exploding mines and shredding barbed wire while rattling the nerves of the Germans waiting on shore.

Under this barrage, scores of landing boats churned forward. Murphy stood in one of them, gripped again by that old, stomach-knotting fear that always came before action. Around him, his men crouched like miserable, soaked cats. Some were seasick; others sat glassy-eyed, lost in the kind of inward withdrawal that came just before battle.

And then, in the midst of dread, Murphy felt the absurdity of the moment. Here they were—small, cold, wet men—thrust into a riddle vast as the sky. He laughed, as he often did when confronted with the enormity of life and death.

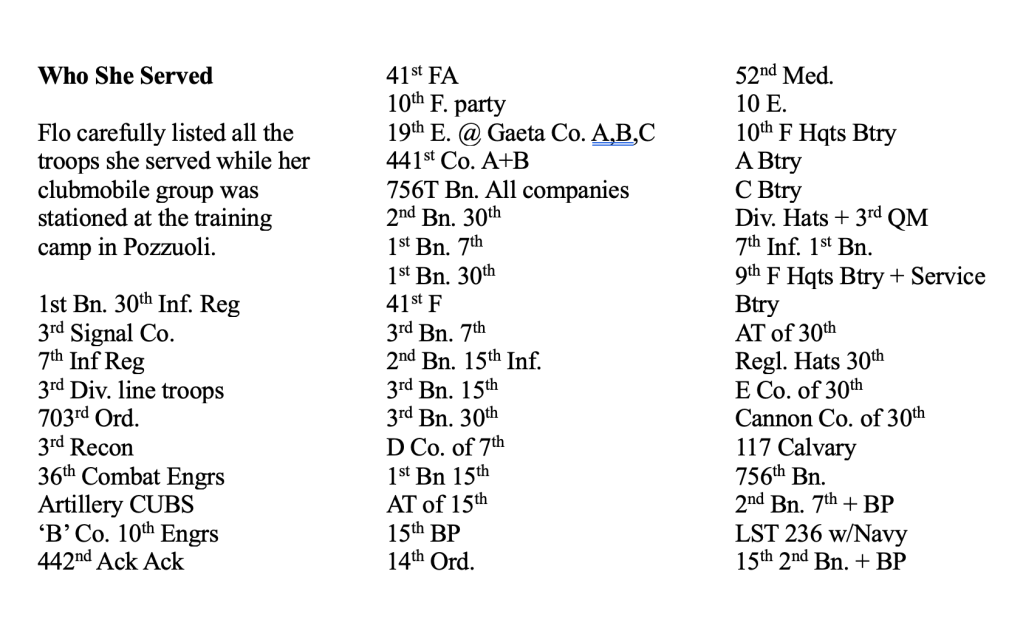

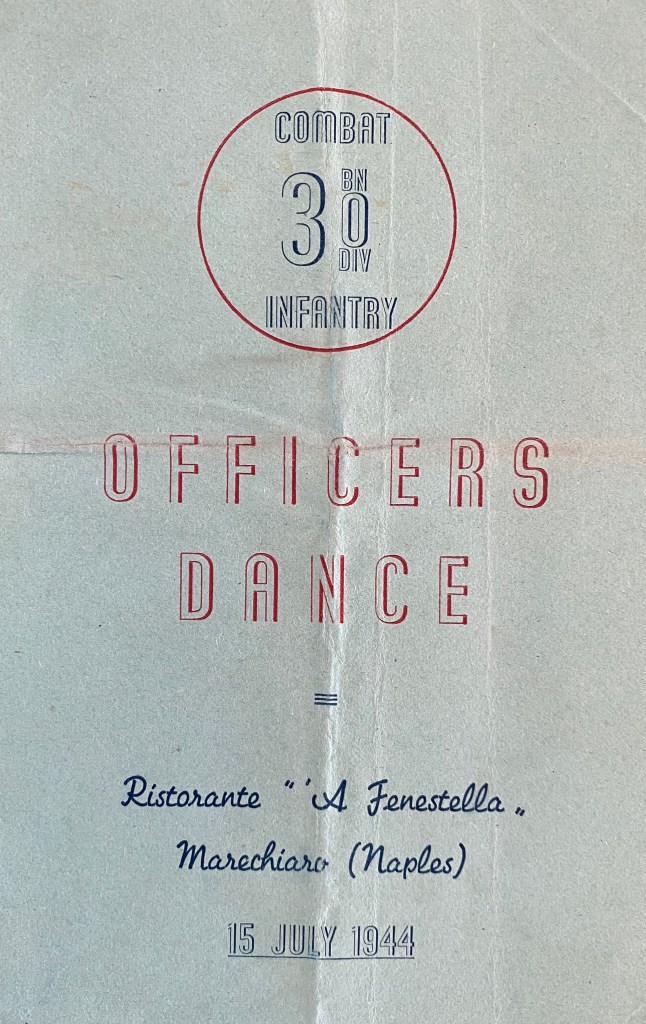

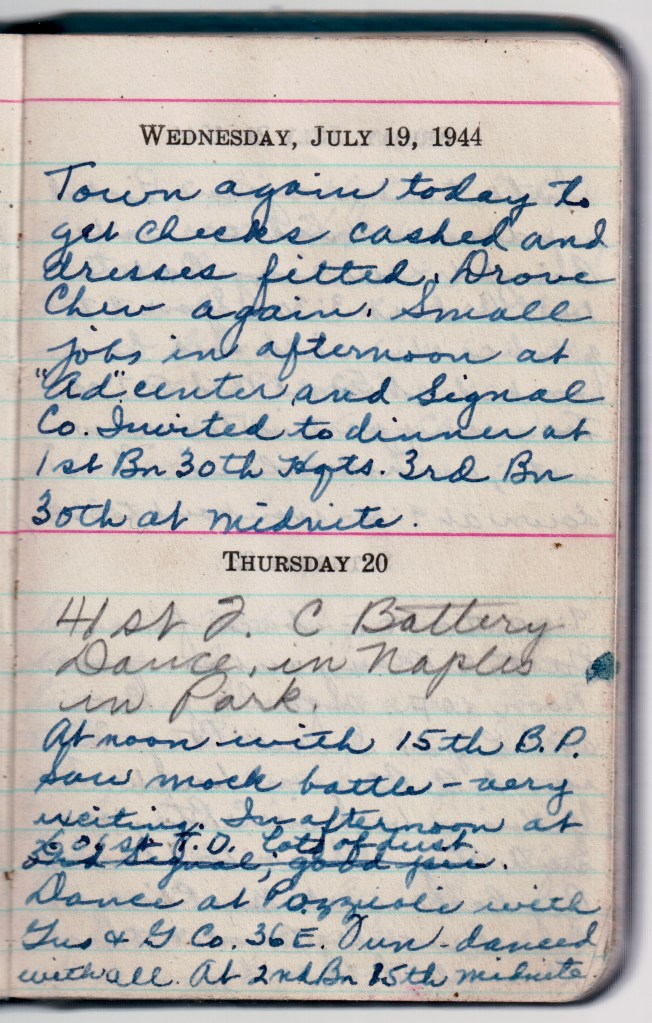

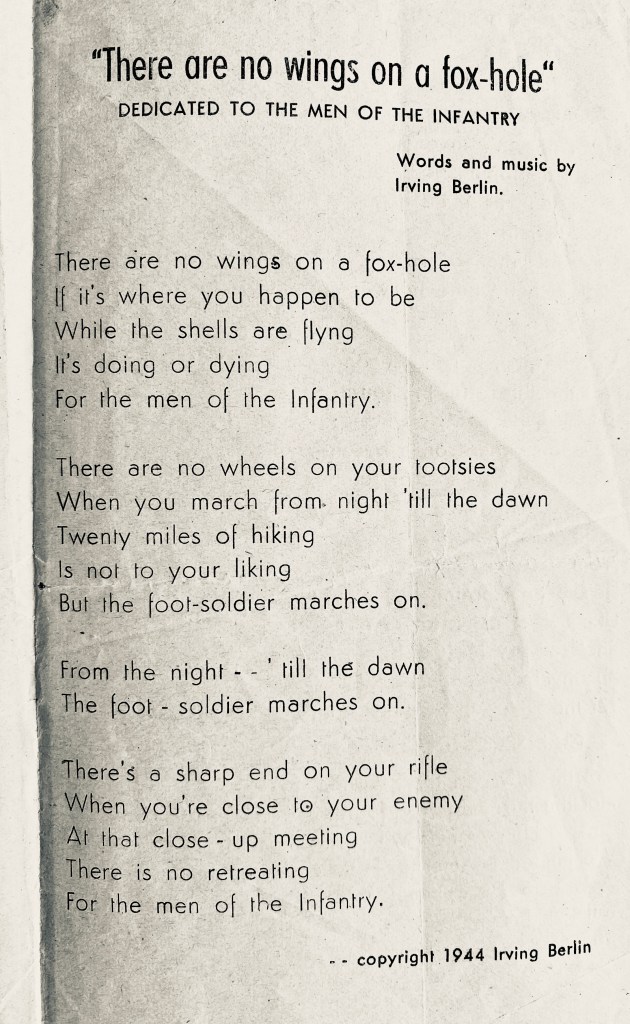

As the boats drew nearer, Murphy tried to rally his men by urging them to sing. They weren’t interested. But singing had long been a way soldiers kept fear in check, anger in rhythm, and marching in step. The Third Division even had its own song—Dogface Soldier—written in 1942 by two of its own, Sgt. Bert Gold and Lt. Ken Hart, both from Long Beach, New York. The division commander, Lucian Truscott, liked it so much he made it official. Third Division soldiers sang it, marched to it, and danced to it.

Years later, in 1955, when Murphy played himself in the film To Hell and Back, the song made its public debut. It became one of the most well-known songs of the war, celebrating not heroes of legend, but the ordinary infantryman—the “dogface” soldier who carried the rifle, slogged the mud, and shouldered the daily weight of the war.

The lyrics—simple, proud, and rough-edged—captured exactly who they were:

I Wouldn’t Give A Bean

To Be A Fancy Pants Marine

I’d Rather Be A

Dog Face Soldier Like I Am

I Wouldn’t Trade My Old OD’s

For All The Navy’s Dungarees

For I’m The Walking Pride

Of Uncle Sam

On Army Posters That I Read

It Says “Be All That You Can”

So They’re Tearing Me Down

To Build Me Over Again

I’m just a Dogface Soldier,

With a rifle on my shoulder,

And I eat a Kraut for breakfast every day.

So Feed Me Ammunition

Keep Me In the Third Division

Your DogFace Soldier’s A-Okay

Ch. 25: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/05/07/ready-to-leave-poor-italy/