My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 40

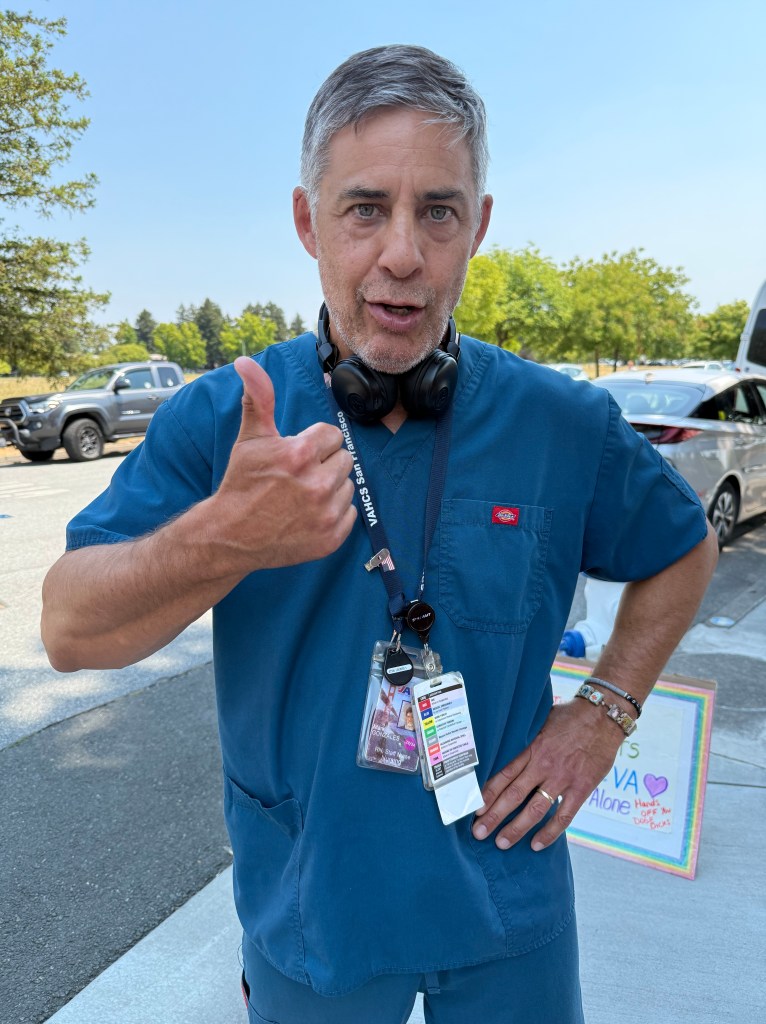

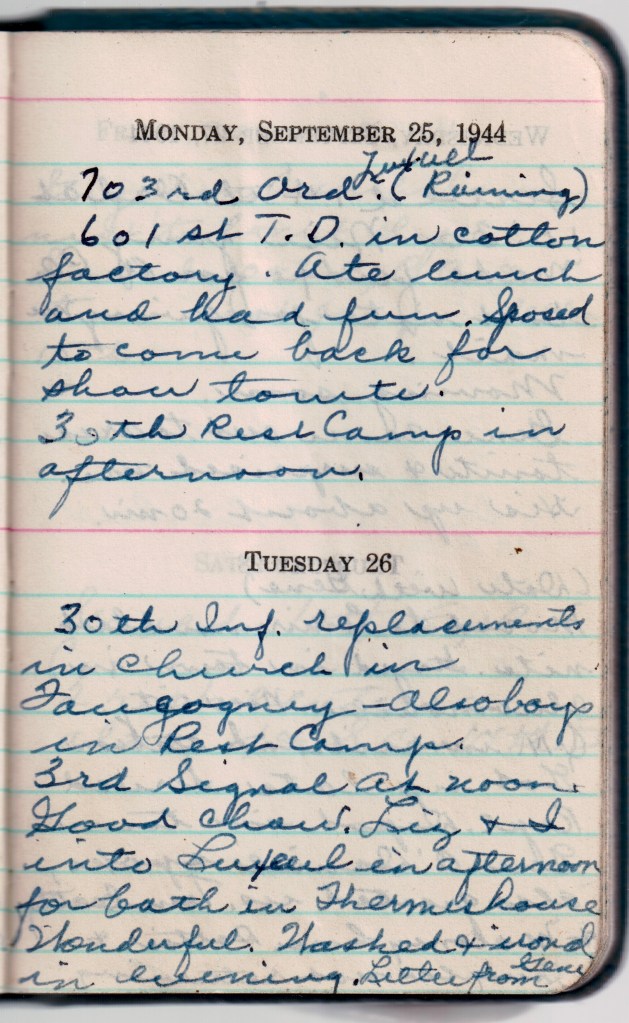

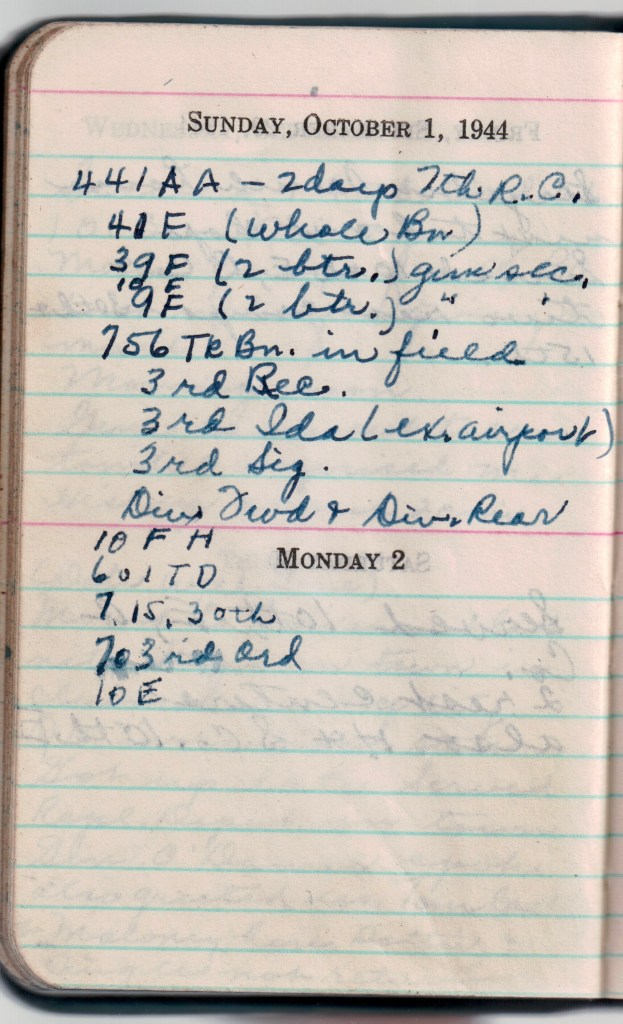

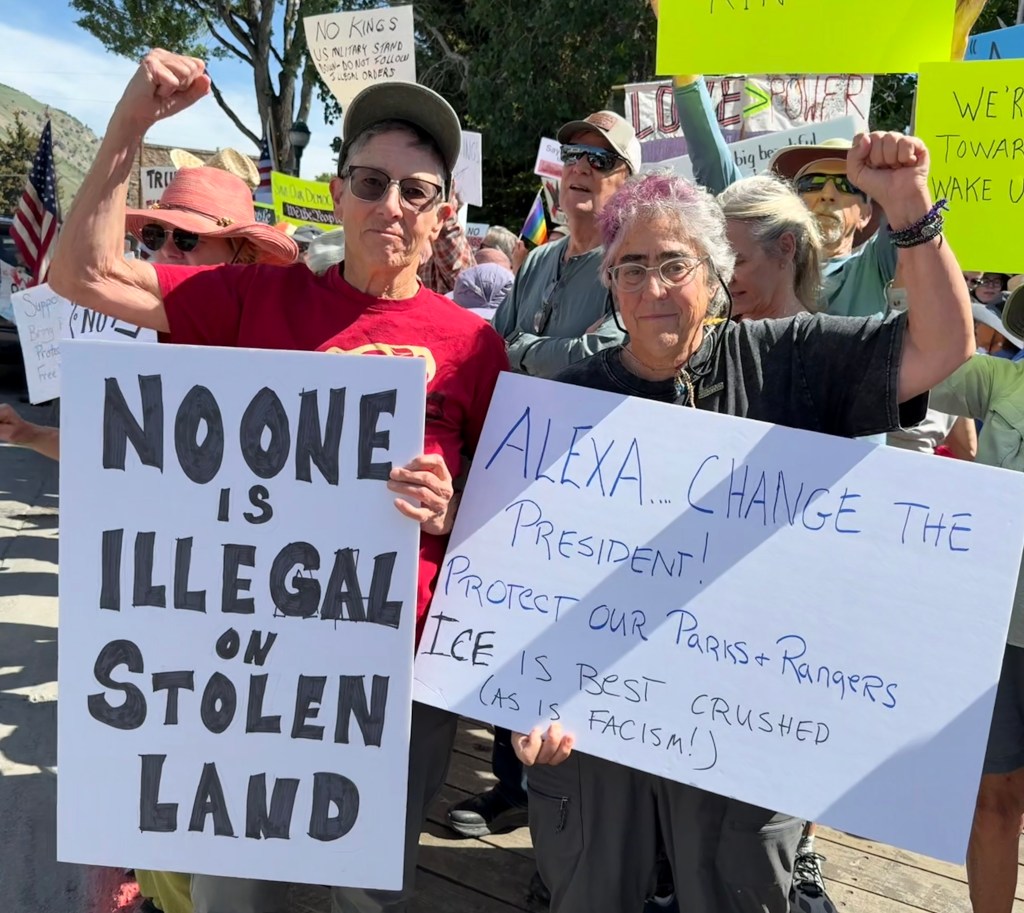

October, 1944. The four-woman crew gets to work, Flo sees Gene before his company goes in the lines, clubmobilers get up near the front lines and they move to a new camp.

A note here about the challenge of research: In 1973, a fire at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) destroyed 16-18 million official military personnel files. Among them were the archived records of the Clubmobile program, making modern-day research into these women’s service difficult.

One helpful resource is The Clubmobile—The ARC in the Storm: A Personal History of and by the Clubmobilers in the European Theater of War During WWII, compiled by Marjorie Lee Morgan. The book includes interviews, diary entries, and photographs. But it focuses solely on the European Theater and omits those who served in the North African and Italian Theaters—even though many of those women, like my mother, also served in France, Germany, and Austria. And these women were the first to enter France and Europe. The book even includes a list of clubmobilers, but no names from the North African/Italian Theater appear, except Forence Wick on the inactive list.

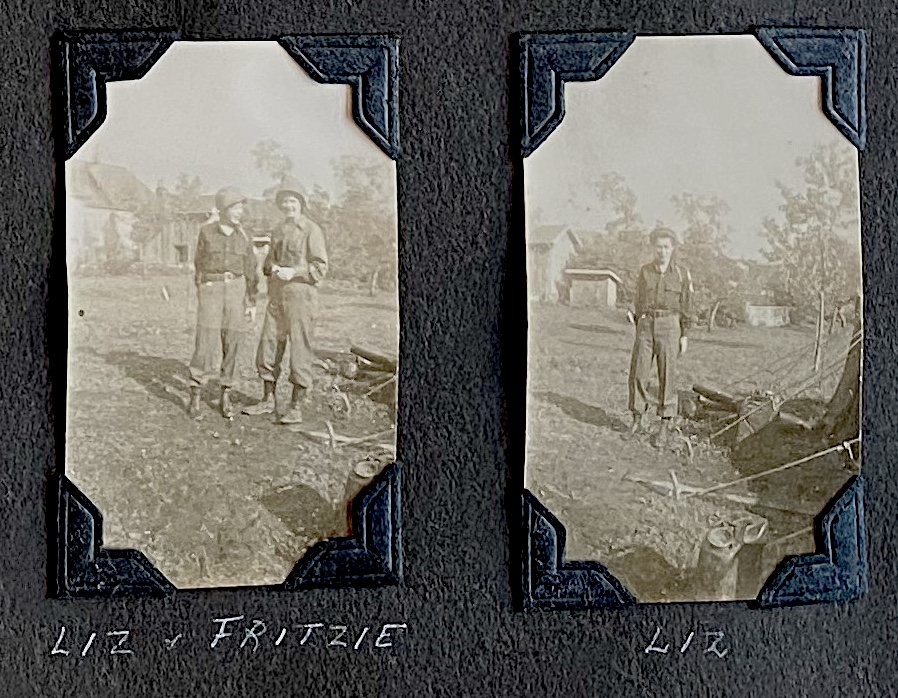

With help from my brother Don, I was able to find some information on Janet Potts and even contacted her daughter. But so far, we’ve found nothing definitive about Fritzie Hoglund (or possibly Hoagland). A newspaper clipping pasted into Flo’s album says Fritzie was from Berkeley, California.

Janet Jenson (née Potts)

Born in New Rochelle, New York, Janet graduated from the Brearley School, attended Barnard and Columbia, and joined the Red Cross in 1944. An accomplished equestrian, she rode in a Third Division “rodeo” at the end of the war.

Janet was one of eight sisters—three of whom served in the Red Cross during the war. Janet was the only one who went to Europe, while the two others served in the South Pacific.

She married Lloyd Jenson in 1946 and had two daughters. Her daughter Susan Jenson told me that Janet often spoke of Flo and that her mother also made a wartime album, which she plans to go through.

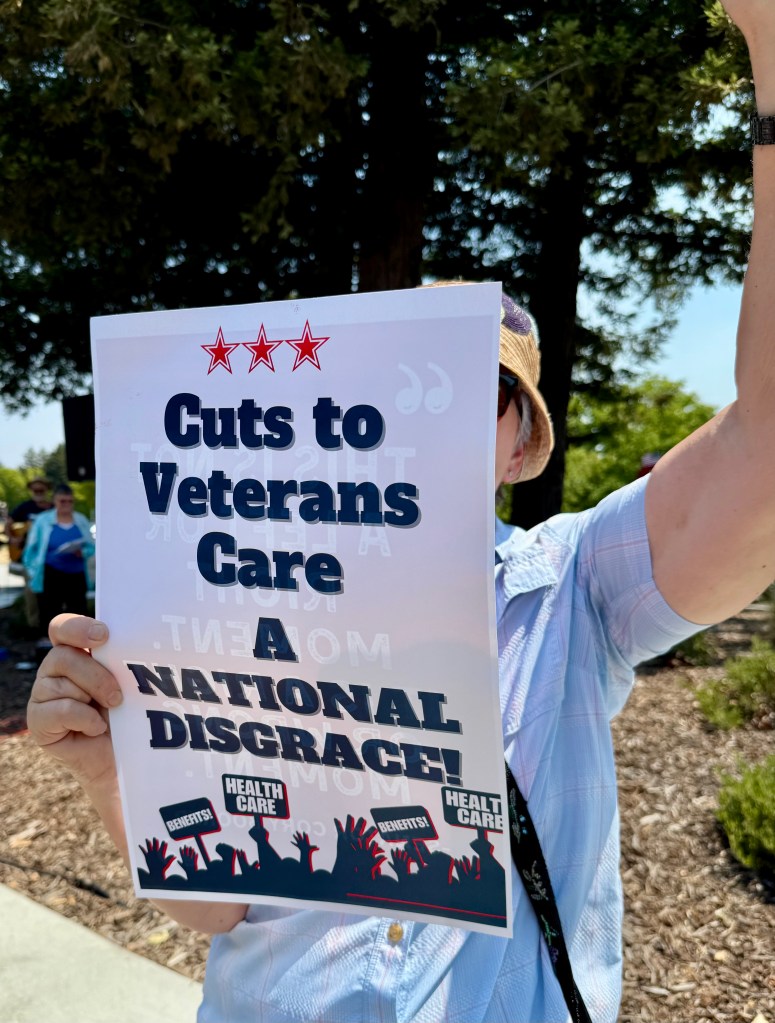

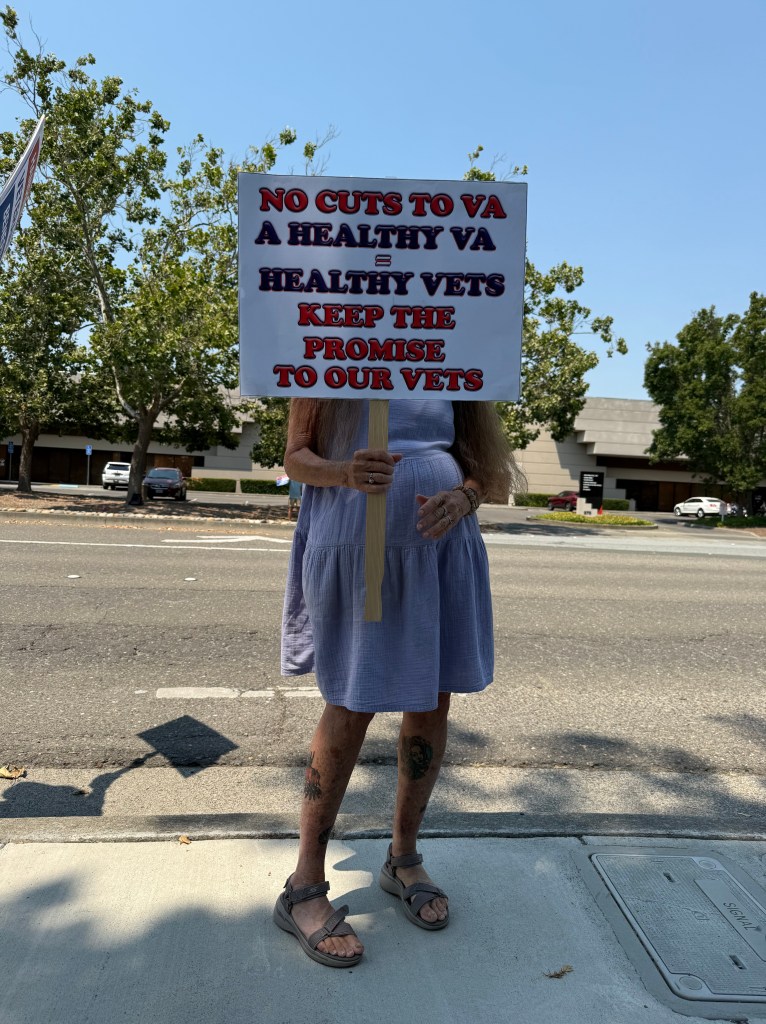

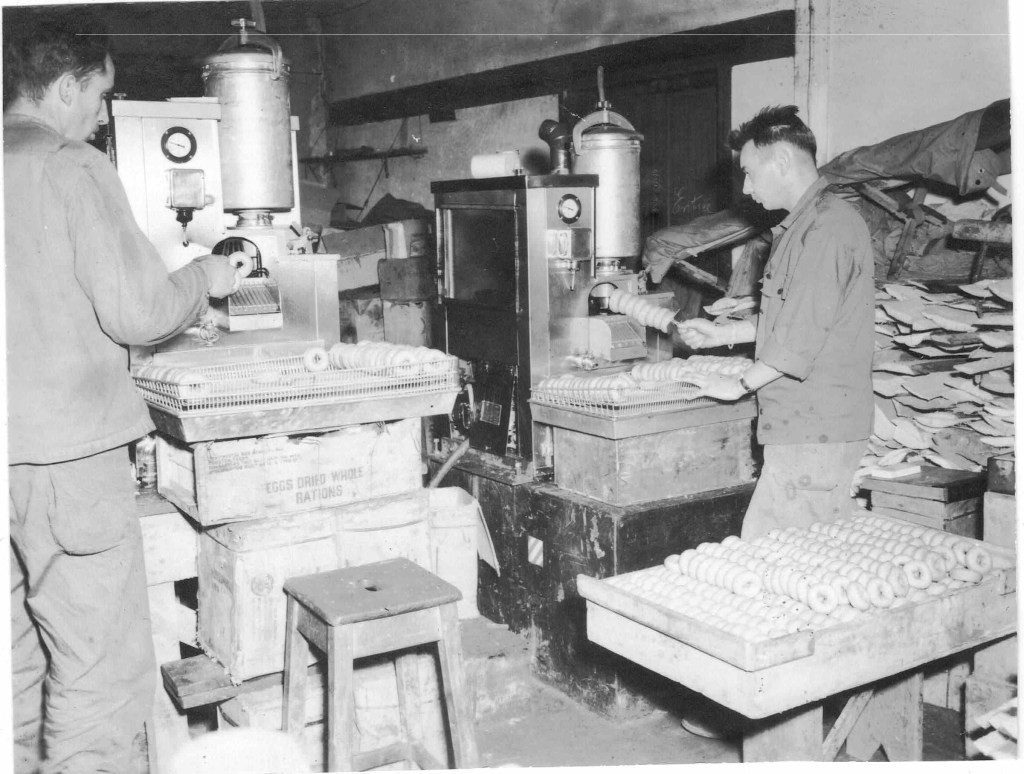

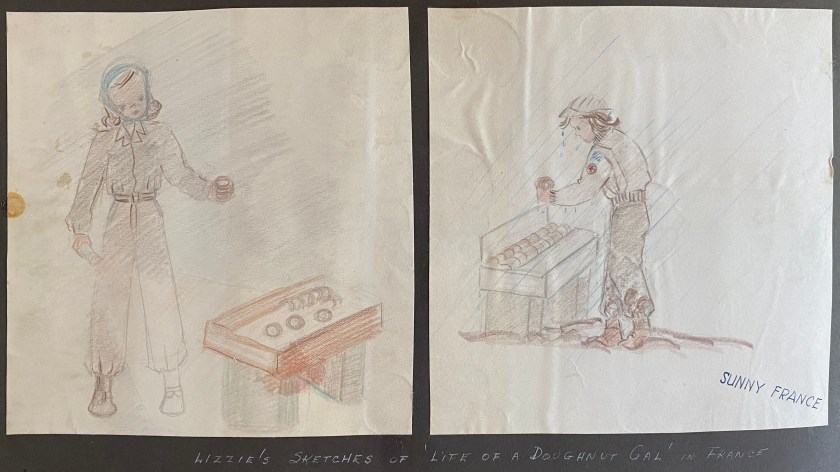

Janet’s daughter wrote, “I personally think there’s far too much focus on donuts in the way the clubmobilers’ work is remembered. These women were brave and generous souls who took on a difficult and emotionally demanding role, offering comfort to exhausted and traumatized troops. As my mother often said, the French sometimes mistook them for camp followers—a euphemism for prostitutes. They had no idea what these women were really doing. But for many soldiers, these were the last warm smiles they ever saw.

“Janet always had kind things to say about Flo. I can imagine the two of them together in a jeep, laughing. It was an adventure—but also full of heartbreak.”

Janet died in 2011, in Denver at age 96.

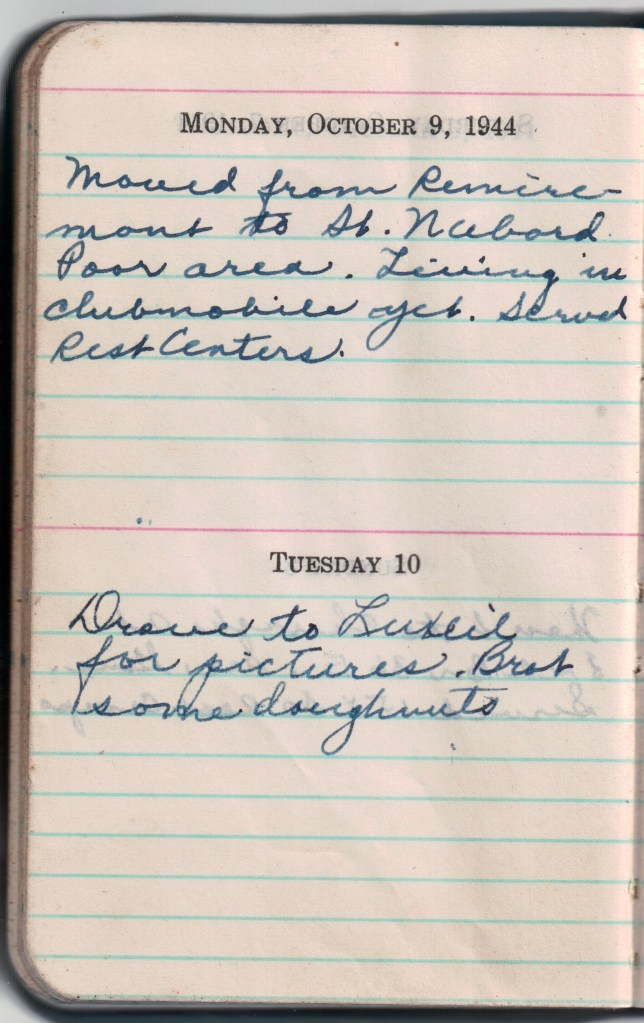

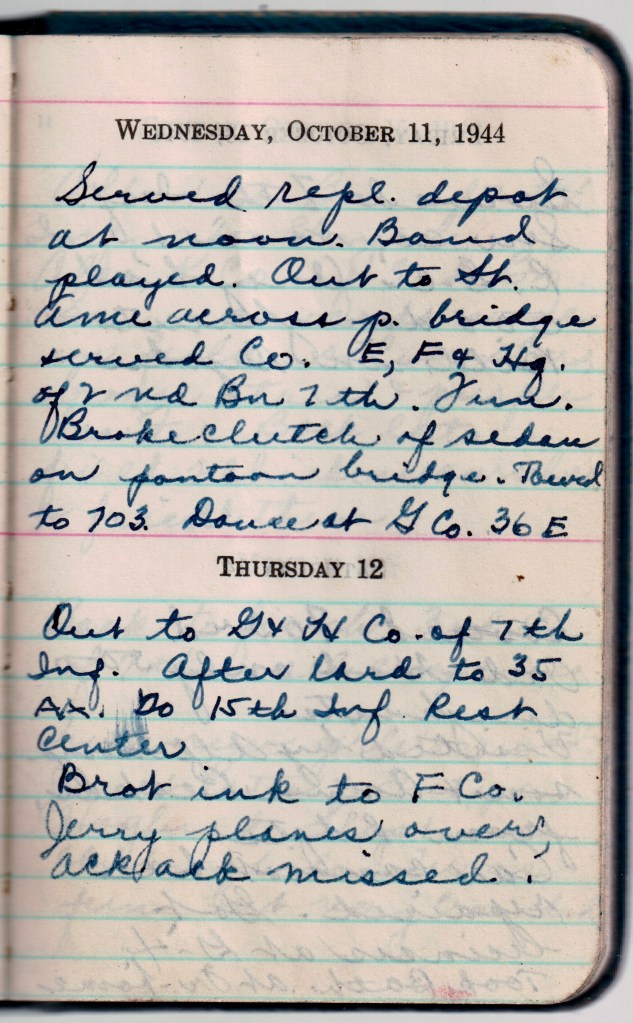

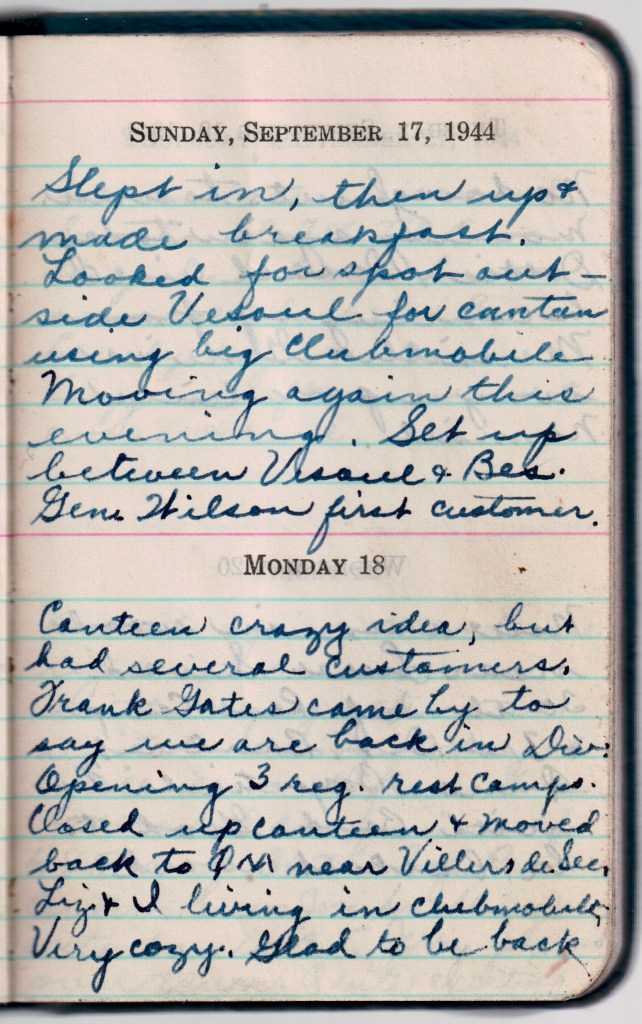

The new four-woman crew slept in the clubmobile. Flo wrote in her diary, “It was fun, but very crowded.” Later, they were issued a tent and new cots.

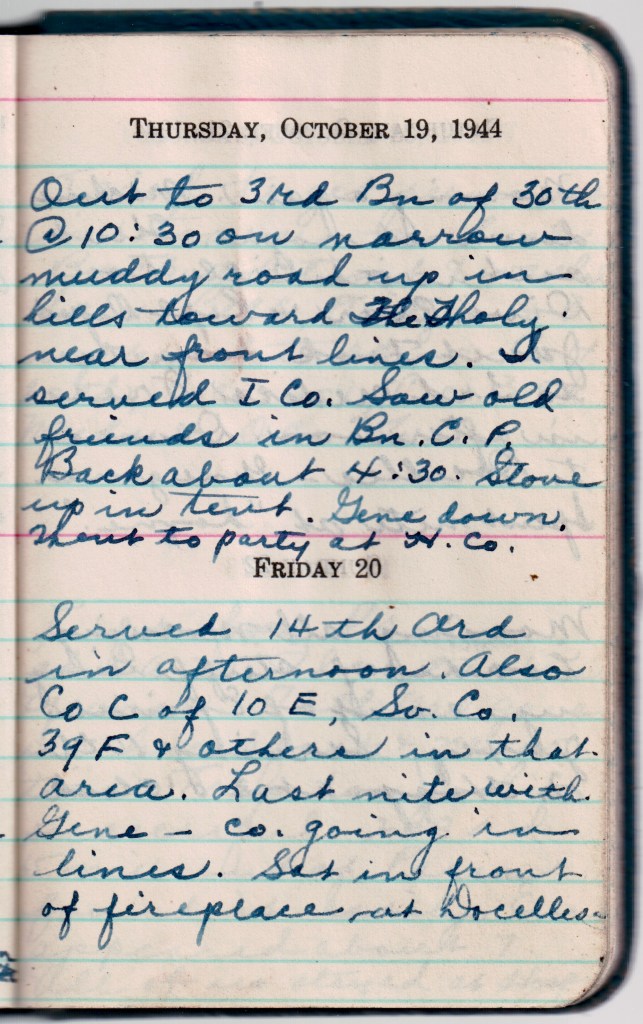

At one point, Flo’s fiance Gene came down from Docelles and surprised her. “Went out to a movie with him,” she wrote. She saw him again on October 19. Then on October 20: “Last night with Gene—co. going in lines. Sat in front of fireplace at Docelles.” The next day in a free afternoon, she drove back to Docelles maybe with the hope of seeing him one last time. She wrote: “Gene gone. Spent night at ‘home.’”

The following morning, Flo and the crew spent hours loading and moving supplies—the clubmobile was relocating to an area near Épinal.

Ch. 41: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/07/20/the-clubmobile-crew-goes-to-paris/