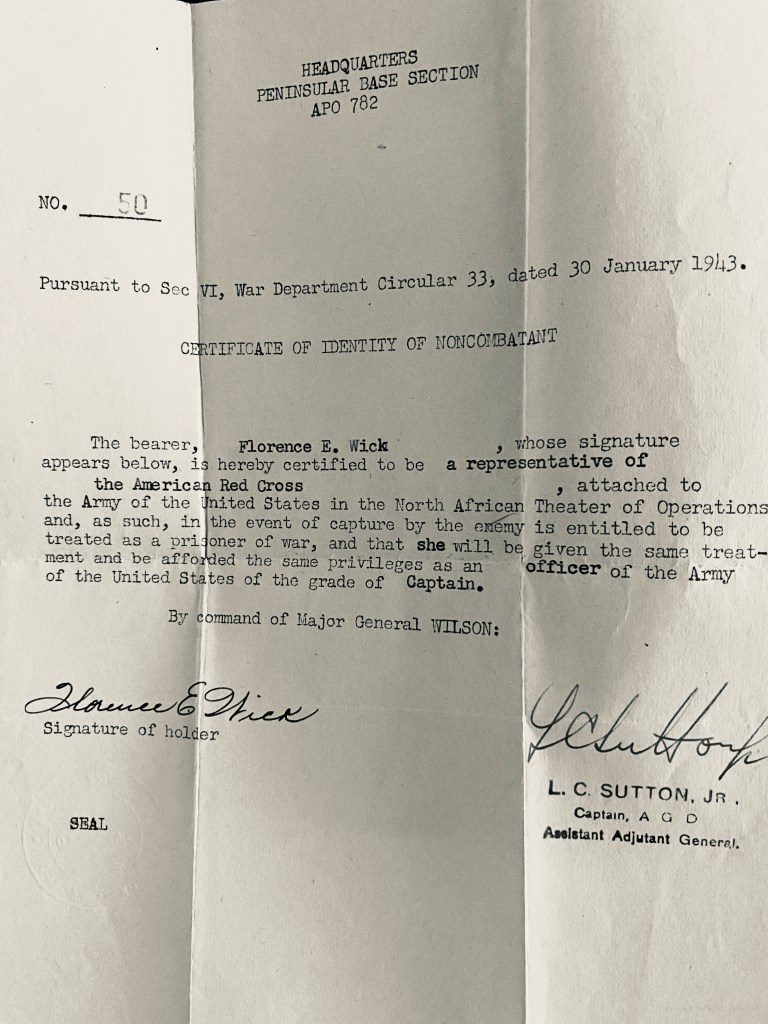

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 23

After Goodbyes, Four Days of Bliss

August 1944 was a month of waiting. The men Flo and her friends had waved off were now at sea, sailing toward the battlefields of Southern France. Their D-Day, scheduled for August 15, loomed heavy in the minds of the Red Cross women left behind. It might be weeks, they were warned, before the coast was clear enough for them to follow. On August 8, the women moved from the camp at Pozzuoli to a residence next to headquarters in Naples.

After days of stifling heat and restless worry in Naples, the women were granted leave. Flo, Dottie, and Isabella fled to Sorrento, trading the grit and noise of the city for something closer to paradise. Flo captured it all in a letter home:

“We have been resting for several days and spent four wonderful days at Sorrento in a lovely old hotel, which is now an officers rest camp. It was peaceful and lovely down there after the hot, noisy, dirty city and seemed like a different world. We were in bathing suits and shorts most of the time, swimming and sailing. They not only have white sails on the boats, but red, Blue and terra-cotta. It is a picturesque site – the sailboats skimming along on that blue, blue water with veri-colored sails.

In her diary Flo wrote about her flirtation with a cute French officer in Sorrento. She called him a “very romantic boy.”

“Italy has its good points and they are nearly all scenery. We took the one-day boat excursion trip to Capri and it is as romantic and lovely as all the songs and posters say. It is out of this world and is surrounded by the clearest, bluest water I’ve seen. The island itself is quaint– abounding in all kinds of flowers, trees, lovely shrines and cathedrals, which date back to the 15th century.

“To make my few vacation days even more unusual and romantic, I met a cute French officer, who made a big hit with all – male and female – staying at the hotel. He spoke a very few words of English and I no French, but we got along beautifully and I took a great deal of kidding about it. Even in his broken English, he was quite a smoothie, and so sincere about it all. They are such sentimentalists, but confidentially I prefer them to the English.”

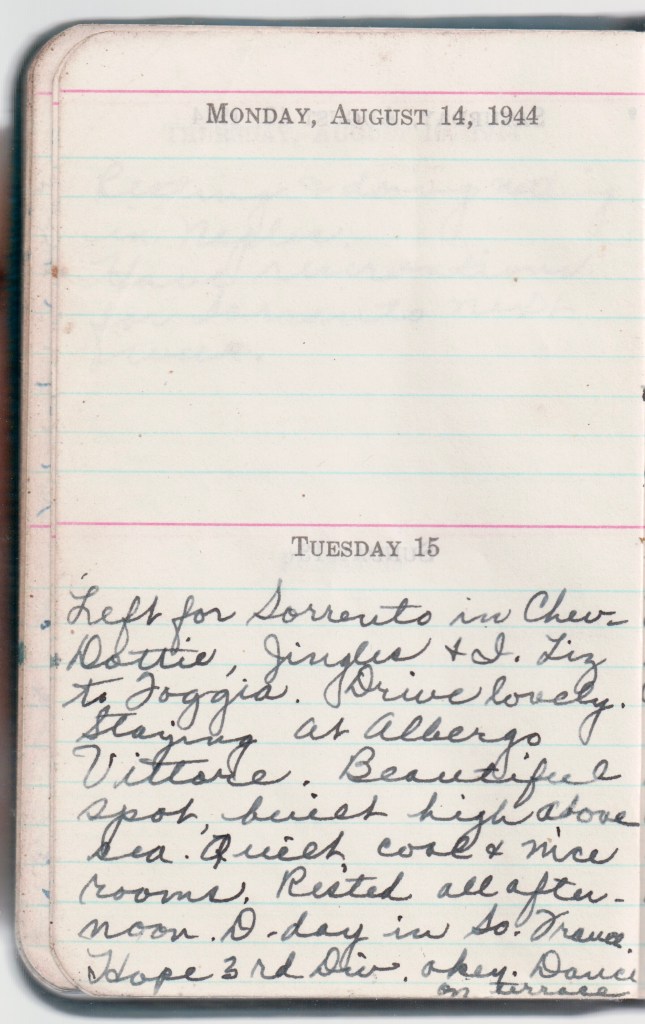

Flo wrote about their trip to Sorrento and Capri in her diary

They sailed to Capri, where the sea was so blue it looked unreal, and the hillsides spilled over with flowers and ancient shrines. Flo met a young French officer, charming even in broken English, and spent a day with him swimming, sailing, and dancing under the southern sun.

In her diary, she noted the date — August 15 — and scribbled the words: “Hope 3rd Div. okey.” She took a drive along the Amalfi coast, marveling at the villages clinging to cliffs above the sea. For a moment, the war felt far away, almost unreal.

But when the four days ended, reality closed back around them. Returning to Naples, Flo and the others slipped once more into the long, anxious business of waiting — and worrying about the boys they had left behind. She wrote in her diary, “May be here for another two weeks. Invasion going well, but worry about boys and especially Gene. Hope he escapes.”

Ch. 24: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/05/02/operation-dragoon-the-landing/