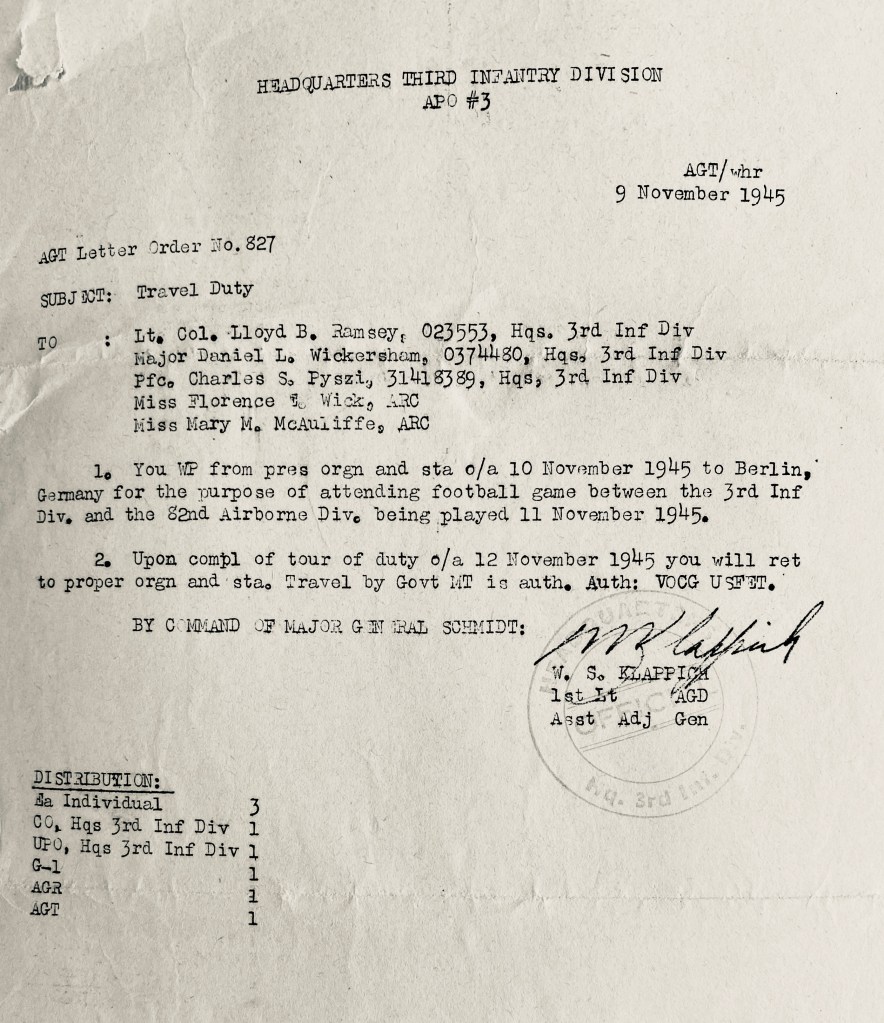

Mary McAuliffe Joins the ARC Crew

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 96

Mary McAuliffe Joins the ARC Crew

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 96

The agreement marked a territorial change in the occupied zones

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 93

Flo attended the historic Russian–American conference in Wanfried, Germany, where the Wanfried Agreement was signed on September 17, 1945. The agreement was a post–World War II territorial exchange between U.S. and Soviet occupation authorities, finalized in English and Russian, to resolve a logistical problem along the Bebra–Göttingen railway. A roughly 2.7-mile stretch of this crucial rail line briefly crossed into the Soviet zone near Wanfried, disrupting traffic vital to U.S. connections between southern Germany and the American-controlled port of Bremerhaven. To secure uninterrupted U.S. control of the line, two villages in Soviet-occupied Thuringia were exchanged for five villages in American-occupied Hesse. The agreement, informally known as the “Whisky-Vodka Line,” stands out as a rare, peaceful, and highly localized negotiation between the two superpowers in the tense early months of the occupation.

Ch. 94: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/02/07/english-americans-russians-party/

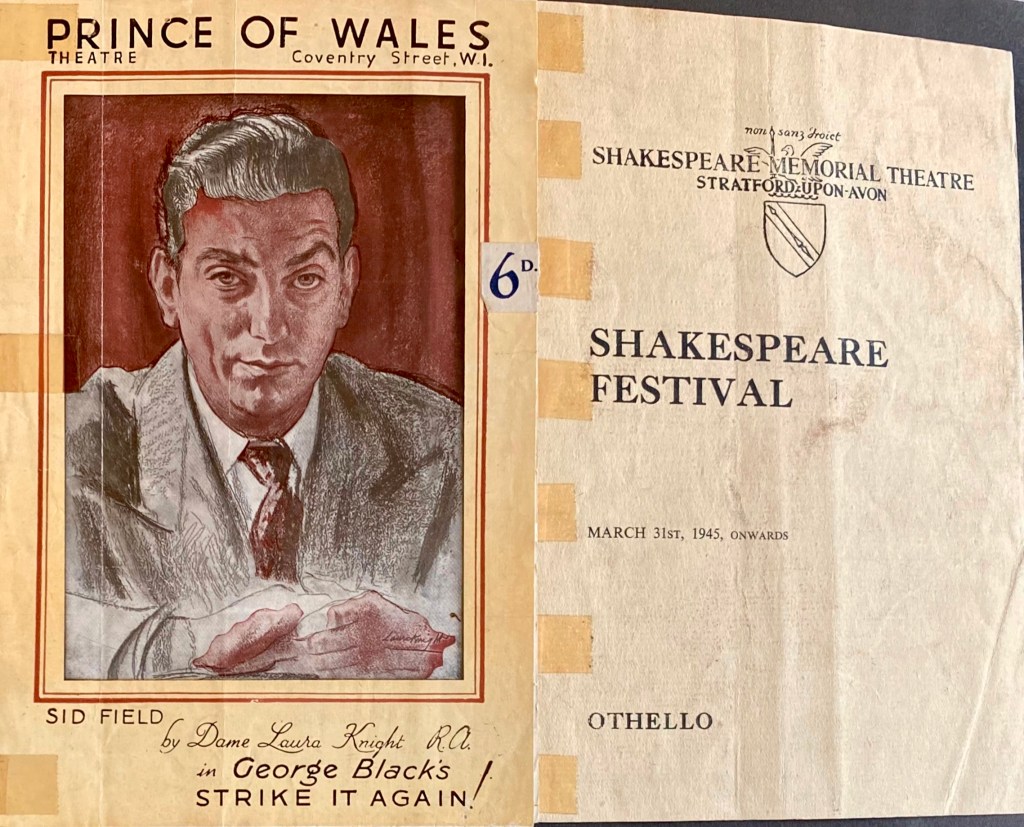

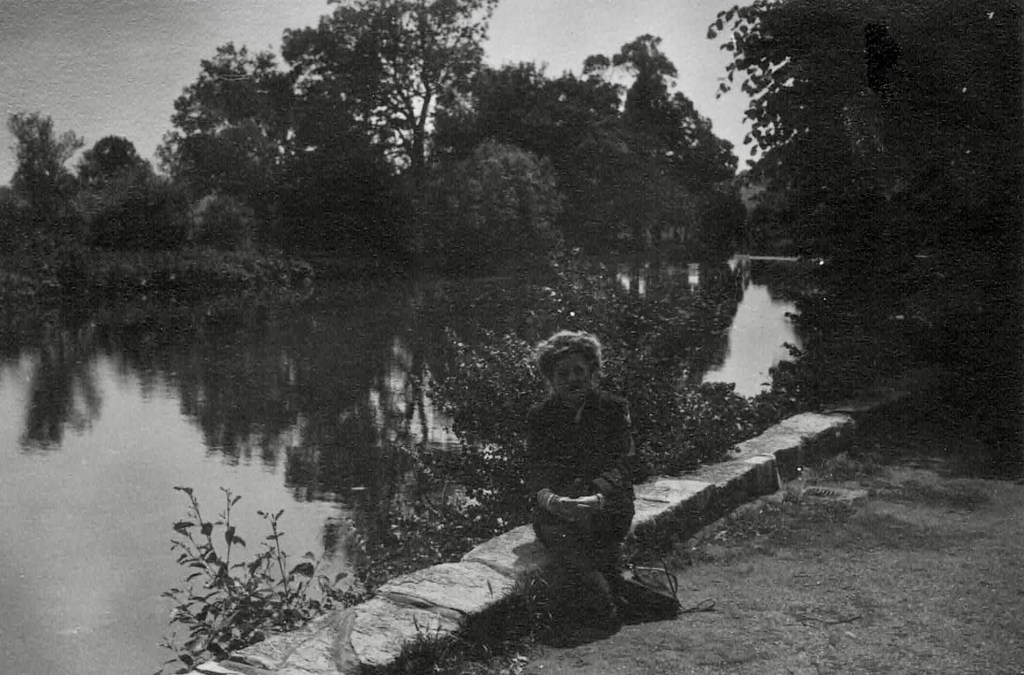

Flo gets to see some Shakespeare too

Ch. 84 My Mother and Audie Murphy

Stratford-upon-Avon, as we all know, is the 16th-century birthplace and burial place of William Shakespeare. The medieval market town in England’s West Midlands is about 100 miles northwest of London. The Royal Shakespeare Company still performs his plays in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre and adjacent Swan Theatre on the banks of the River Avon. Flo visited in mid-June, 1945.

Stratford-upon-Avon had faced the threat and effects of the Blitz through scattered incidents and as a sanctuary, rather than being a central target for sustained bombing like larger industrial or military centers. During the war the town provided refuge, with people from heavily bombed areas like Birmingham coming to Stratford for quiet and respite from the relentless night raids.

Ch. 85: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/01/04/audie-murphy-comes-home/

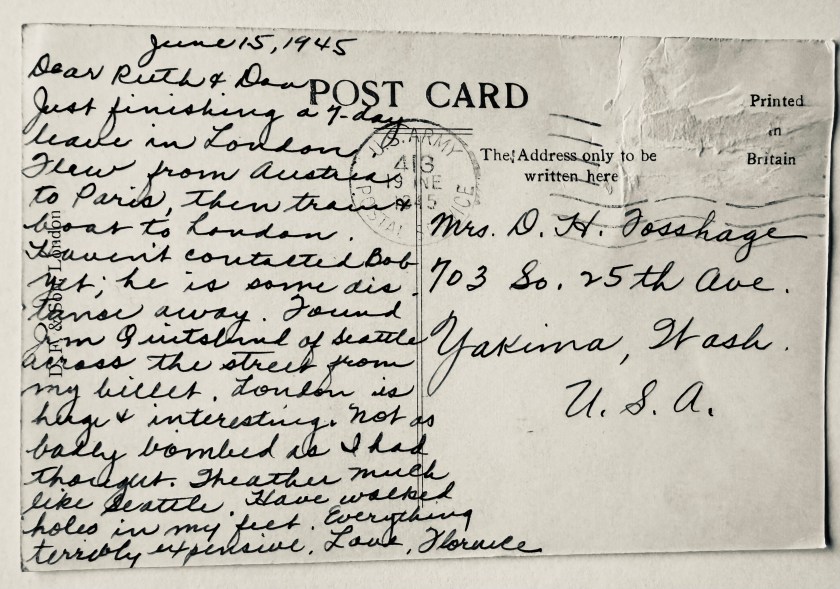

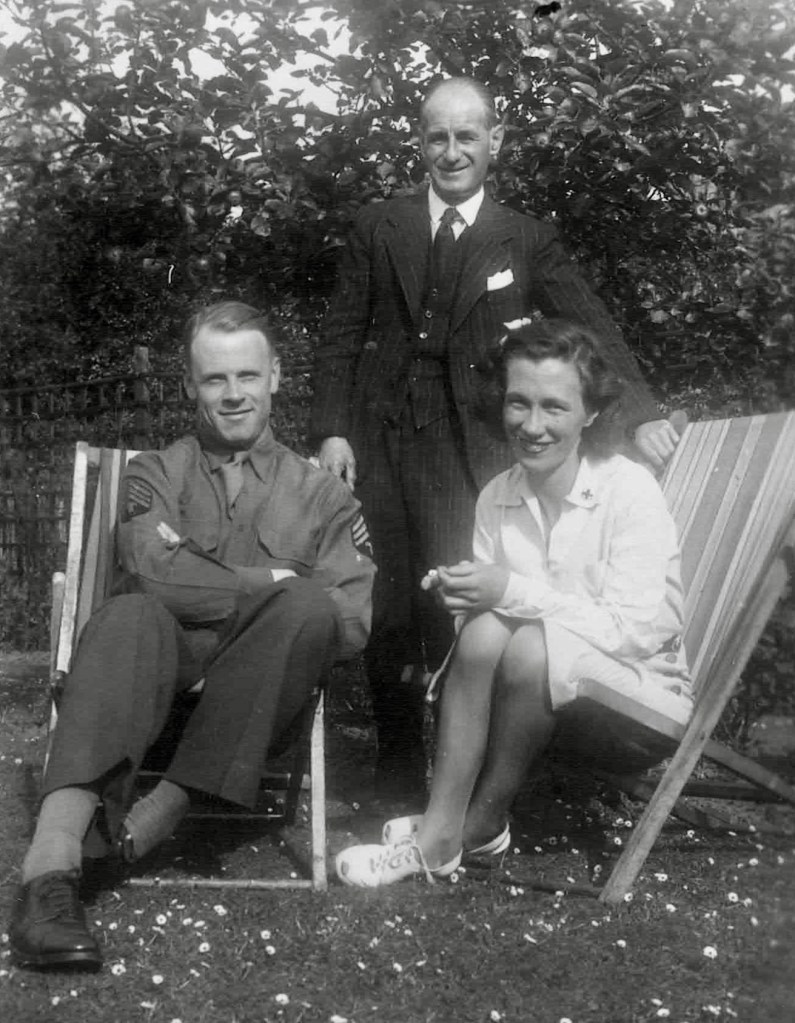

“Have walked holes in my feet”

Ch. 83: My Mother and Audie Murphy

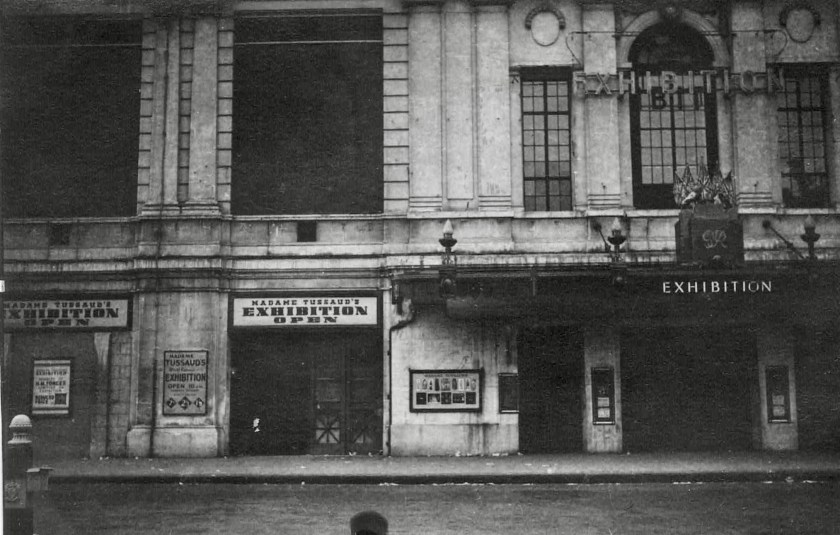

Flo arrived in London in June, 1945 for a seven-day leave. In a postcard to her family Flo wrote:

“London is huge and interesting. Not as badly bombed as I had thought. Weather much like Seattle. Have walked holes in my feet. Everything terribly expensive.”

She ran into a friend from Seattle, Jim Quitslund, who was staying across the street from her billet.

With Jim Quitslund, the Army friend from Seattle, billeted across the street in London.

The Blitz focused on London

Starting on September 7, 1940, London faced 57 straight nights of bombing by Nazi Germany, part of a concentrated eight-month campaign known as the Blitz.

Flo wrote that the bombing damage was not as bad as she had thought, but she may not have made it to the East End, which sustained the most bombing. The Luftwaffe raids were aimed at disrupting the British economy by targeting docks, warehouses, and industrial areas. The damage was devastating, characterized by massive fires, widespread destruction of working-class housing, and high civilian casualties there.

An estimated 18,688 civilians in London were killed during the war, 1.5 million were made homeless. 3.5 million homes and 9 million square feet of office space were destroyed or damaged.

Ch. 84: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/01/01/a-visit-to-stratford-on-avon/

Clubmobilers bid farewell to soldiers going home

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 80

When Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, the U.S. Army in Europe suddenly had to shift from fighting to occupying a defeated nation. More than two million soldiers now had to be sorted into three paths: those who would stay in Germany as an occupation force, those who would be sent to the Pacific for the expected invasion of Japan, and those who would finally go home. Because the Army had more men than it needed for occupation and redeployment, it also had to begin discharging veterans fairly and quickly.

General George C. Marshall had foreseen this challenge. Drawing on hard lessons from the chaotic demobilization after World War I, he ordered the Special Planning Division in 1943 to craft a method that would release soldiers on an individual basis rather than by entire units. With divisions in Europe filled with late-war replacements, unit-based demobilization was impossible—and delay risked unrest among idle troops.

After gathering input from commanders worldwide, the army created the Adjusted Service Rating Score, universally known to GIs as the point system. It offered an objective way to determine who went home first. Points were awarded for time in service, time overseas, combat campaigns, decorations, wounds, and dependent children:

This system became the backbone of America’s demobilization in Europe.

Flo stayed on in Europe until March, 1946, and I had assumed she signed up to serve in the Red Cross during the occupation. But I think she was just as anxious to return home as all the other American soldiers and staff–she just couldn’t get out any sooner. It’s not clear whether Red Cross workers received points, or whether they even fell under the rating score system.

Ch. 81: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/12/20/regimental-review-schloss-klessheim/

Flo stood at the border and looked across the Alps into Austria

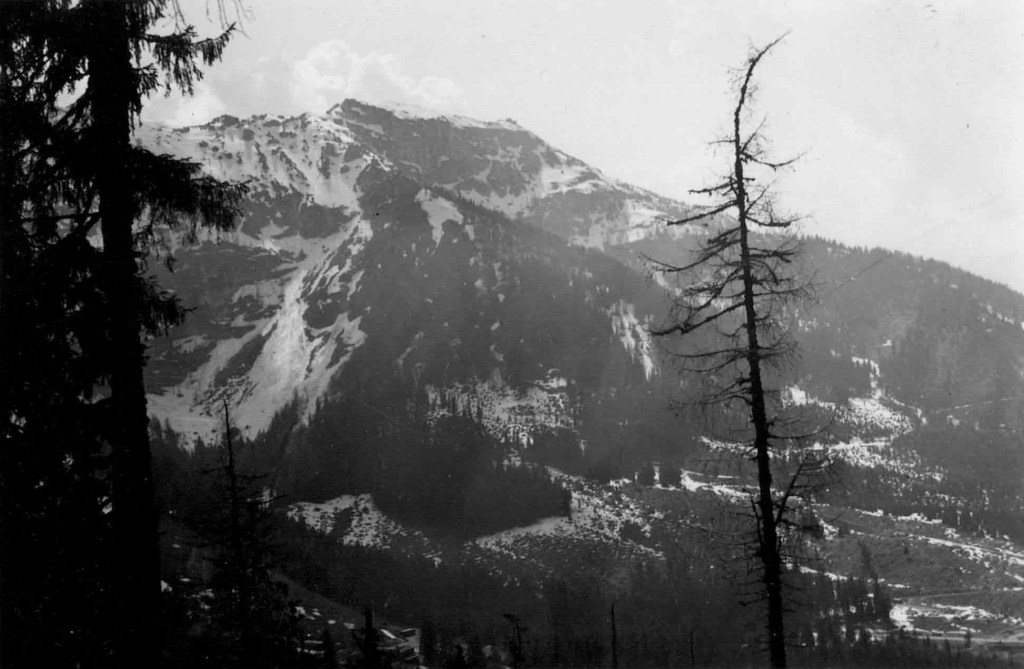

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 77

In May, 1945, just after the end of the war, Flo must have been excited to summit the Brenner Pass and see into Austria. Brenner Pass has long been a strategic gateway through the Alps, and its role intensified during World War II. After Germany annexed Austria in March 1938, the pass suddenly lay deep inside Hitler’s expanding Reich. Two years later, on 18 March 1940, Hitler and Mussolini met there to reaffirm their Pact of Steel.

When Italy signed an armistice with the Allies in 1943, Germany moved quickly to seize the pass and push the border with Mussolini’s new puppet regime far to the south. By 1945, American troops occupied the area, and the pass was returned to Italy once the war ended. In the chaotic aftermath, Brenner Pass also became one of the escape routes, part of the “ratlines” used by fleeing Nazi leaders. After the war, the pass once again marked the border between Italy and the newly independent Republic of Austria.

Flo didn’t ID these soldiers

Ch. 78: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/12/12/3rd-division-salzburg-rodeo/

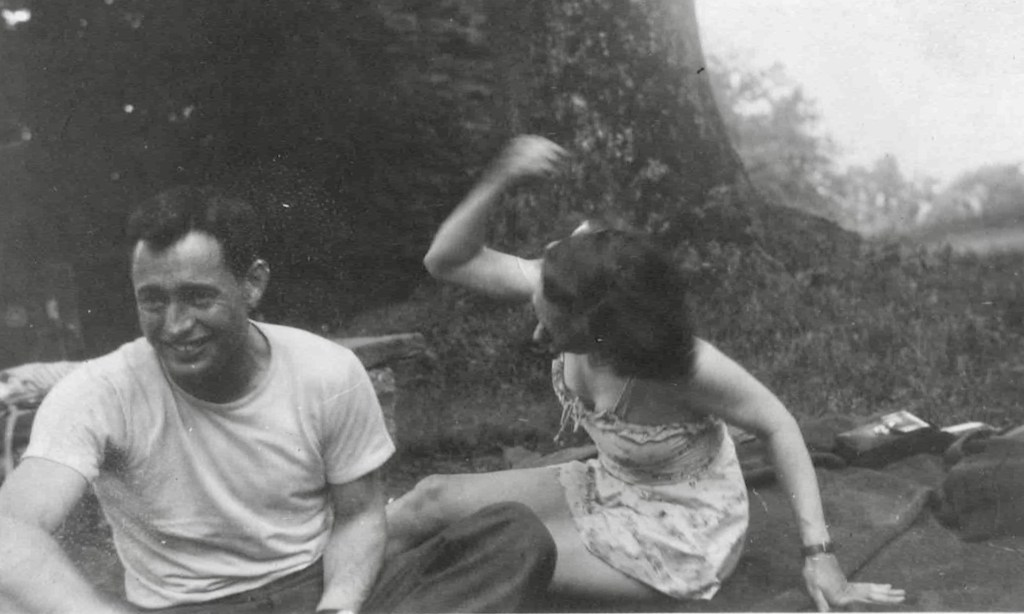

Flo Celebrates with Chris Chaney, Janet and Jens

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 76

On June 25, 1945, Flo turned thirty-two, and her friends gathered to give her a proper birthday celebration. She spent the day with her clubmobile partner, Janet Potts, along with Janet’s boyfriend, Capt. Lloyd (Jens) Jenson, and Flo’s own boyfriend, Lt. Col. Chris Chaney. All four arrived in uniform as they wandered through the fortress castle that served as headquarters for the 15th Infantry above Salzburg. The women wore their Red Cross-issued dresses; the men their Army greens. They teased one another, snapped photographs in the grand corridors, and convinced Flo to pose in the old stocks for a laugh.

Later, they changed into civilian clothes and headed out for a picnic. Indoors, there was a birthday cake, and they captured more pictures—two couples who looked close, relaxed, and hopeful in the early summer after the war’s end.

These became the last images, and the last mention, of Flo’s relationship with Chris Chaney. The photographs made them seem comfortably paired, and although Janet and Jens eventually married, Flo and Chris did not stay together. She kept no letters from him after the war.

What became of him remained unclear. The two had talked about traveling to Paris and England, plans that never materialized. Most likely, he received an early chance to go home and took it. As a highly decorated officer with a Silver Star, he would have been near the front of the line for repatriation. Flo’s life moved forward, and whatever they had envisioned together faded with the summer.

Ch. 77: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/12/12/3rd-division-salzburg-rodeo/

Flo and Janet Get Leave

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 74

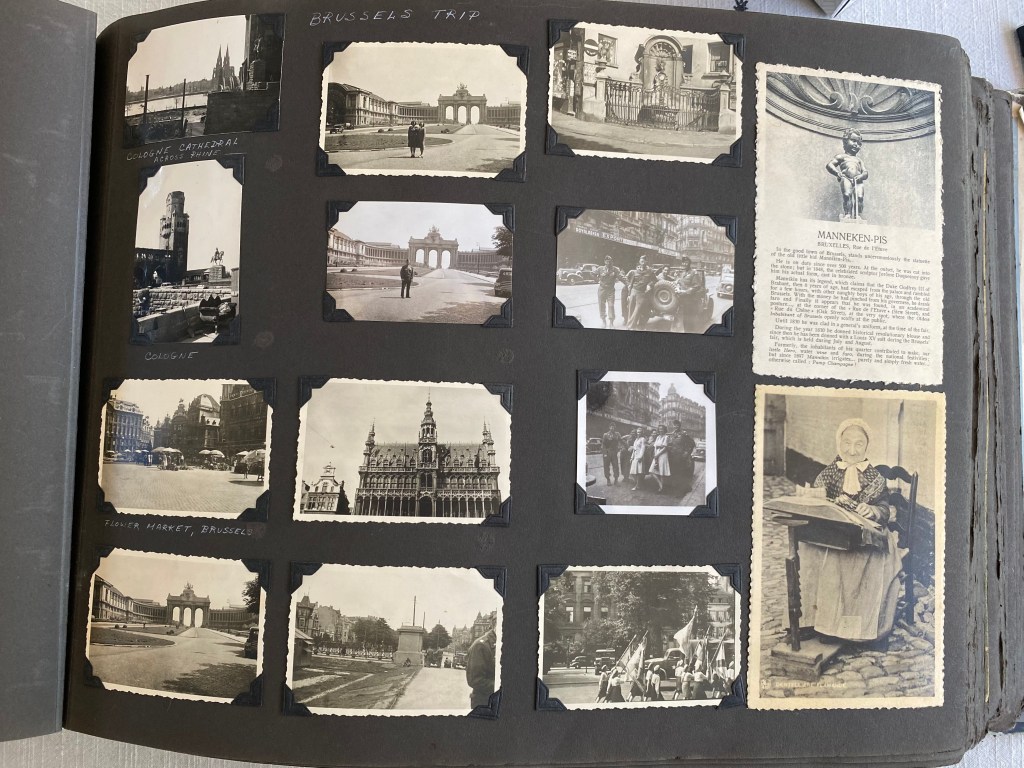

Flo and Janet got leave to travel to Brussels probably in June, 1945. In her inscriptions on this page in her album, Flo doesn’t indicate how they travelled the 450 miles from Salzburg, stopping in Cologne, nor whether they went with the soldiers in these pictures.

The War in Brussels

Belgium had been under German occupation since 1940, but Brussels was freed in early September 1944. The city of nearly a million people did not expect liberation to come so quickly, and enormous crowds poured into the streets, slowing the Allied advance as they welcomed their liberators. At the same time, Belgian railway workers and the resistance foiled a German attempt to deport 1,600 political prisoners and Allied POWs to concentration camps on the so-called “ghost train.”

The city escaped the widespread destruction seen elsewhere in Europe; it was not subjected to systematic or heavy bombing. The rest of the country was liberated by February 1945.

Cologne Cathedral Survived

When American troops entered Cologne on March 6, 1945, the Cologne cathedral was one of the few major structures still standing. The Gothic landmark became the backdrop to a famous tank battle as U.S. forces took the western part of the city and the Germans withdrew across the Rhine, holding the eastern bank for another month.

Remarkably, the cathedral survived both the battle and years of Allied bombing. Construction began in 1298, but the cathedral wasn’t finished until 1880. Just sixty years later, Cologne was hit by the first of 262 RAF air raids. Nearly a quarter of the city’s 770,000 residents fled after that initial attack, and the population continued to drain away until only about 20,000 remained by the final raid on March 2, 1945.

The cathedral’s twin spires even served as a navigational point for Allied bombers. Though struck 14 times and heavily damaged, the great structure endured, towering over the ruins of the city.

Ch. 75: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/12/01/occupied-salzburg-summer-1945/

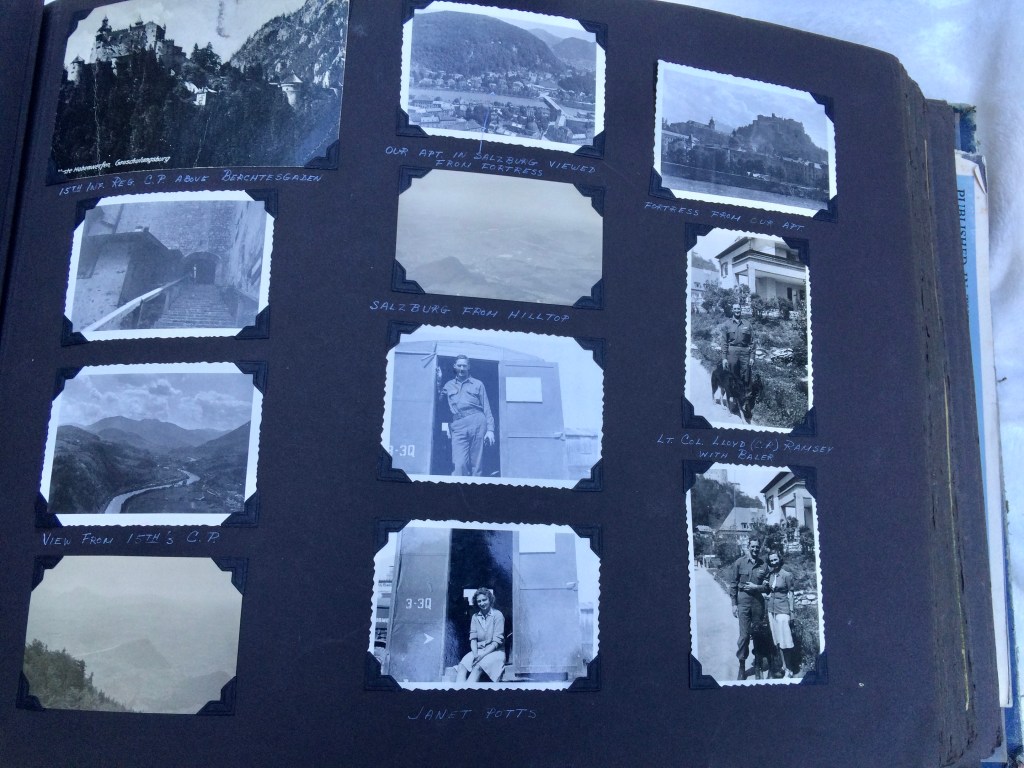

Clubmobilers fall in with 15th Infantry

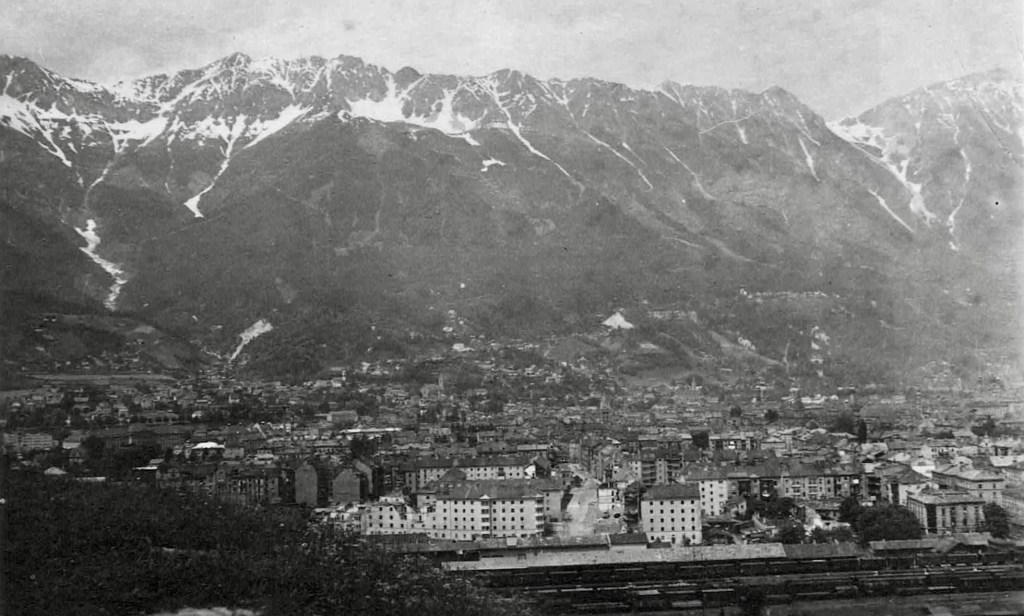

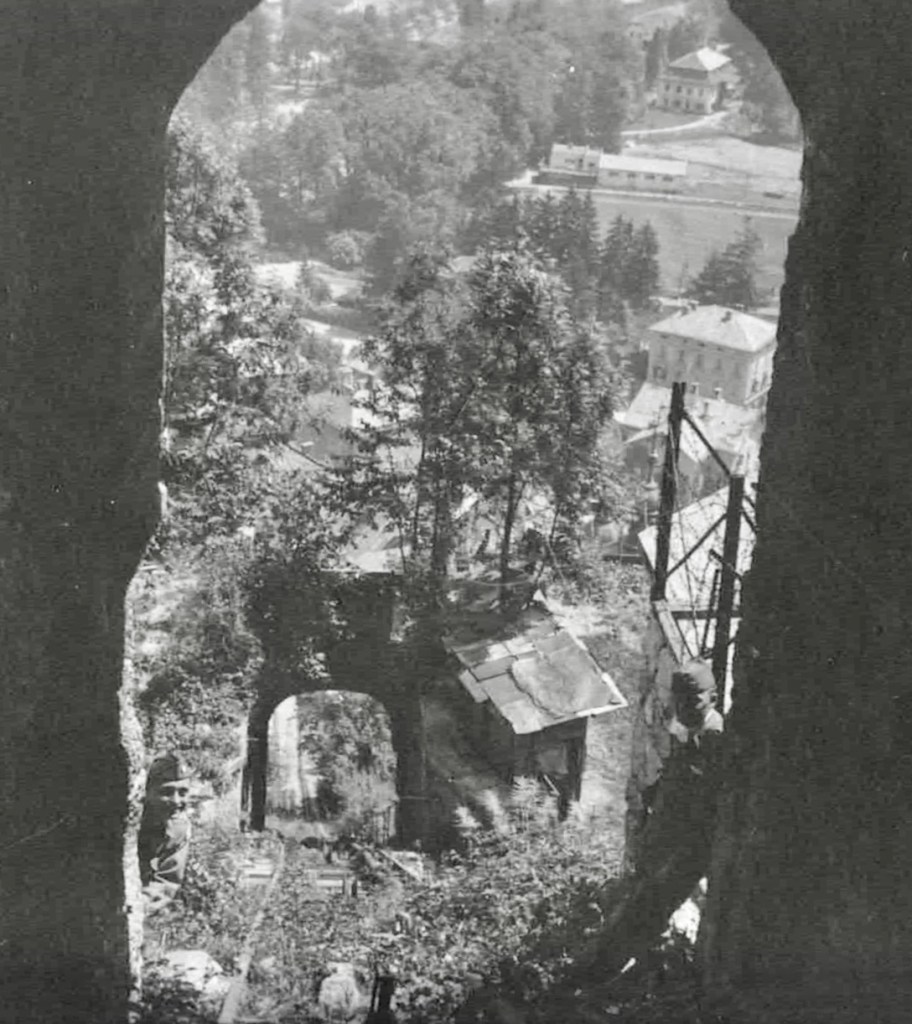

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 73

In May 1945 the clubmobilers settled in an apartment in Salzburg. They were attached to the 15th Infantry Regiment which had taken over a fortress above Hitler’s ruined mountain headquarters at Berchestgaden as their command post. Flo’s photos on this page in her album show scenes of Salzburg, the fortress and the surrounding hills, her sister clubmobiler Janet Potts and Lt. Col. Lloyd (C.P.) Ramsey with dog Baler. In a picture taken from the fortress, Flo drew an arrow pointing to the women’s apartment.

Salzburg, with a population of 36,000, had suffered heavy damage in the war: Allied bombs destroyed nearly half the city and killed 550 people. Much of its Baroque center survived, but rebuilding loomed large.

On May 5, 1945, Salzburg surrendered to advancing U.S. forces without a fight. Many residents greeted the Americans as liberators, relieved that 5½ years of war were finally ending—even if it meant accepting defeat. But the U.S. Army arrived as an occupying power as well. For years, no major political, cultural, administrative, or economic decision could be made without its approval.

Postwar life was marked by severe shortages, especially housing and food. More than 1,000 buildings had already been damaged or destroyed in the 1944–45 bombings, and the U.S. occupiers requisitioned many remaining properties for their own use.

Ch. 74: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/11/27/trip-to-brussels/

The 3rd Division gets credit and Flo was there

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 70

There is still debate over which Allied unit can claim credit for capturing Berchtesgaden in May 1945. The most reliable historical accounts indicate that the 3rd Infantry Division, specifically the 7th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Maj. Gen. John “Iron Mike” O’Daniel, reached the town on May 4, 1945, and accepted its surrender without resistance. They were the first American combat troops to enter the town itself.

However, popular history has sometimes credited the 101st Airborne Division’s Easy Company—made famous by Stephen Ambrose’s Band of Brothers—with the “liberation” of Berchtesgaden. Easy Company did arrive on May 5, the day after the 3rd Division. Their presence, and the power of their postwar memoirs, contributed to the widely repeated but inaccurate claim that they captured the town.

Complicating matters further, elements of the French 2nd Armored Division, advancing from the south, also reached the Obersalzberg at nearly the same time. French armored troops were already present at the SS guardhouse near the entrance to the Obersalzberg complex when the Americans arrived on May 4. So while the 3rd Infantry Division is generally recognized as having taken Berchtesgaden, the French made the first approach to the mountain enclave.

What is clear is that Flo arrived very shortly after the area had fallen to Allied forces, when the military presence was still active and the ruins still fresh.

Berchtesgaden and the Obersalzberg Complex

Berchtesgaden, in the Bavarian Alps, served as Hitler’s alpine headquarters and a central site of Nazi state power. The Obersalzberg complex above the town contained residences, administrative buildings, and security installations used by Adolf Hitler and other high-ranking Nazi leaders, including Martin Bormann and Hermann Göring.

Key components included:

• The Berghof: Hitler’s primary residence, significantly damaged in a massive Allied bombing raid on April 25, 1945.

• The Eagle’s Nest (Kehlsteinhaus): A mountaintop chalet and diplomatic reception site, built for Hitler’s 50th birthday.

• SS Barracks and Guard Posts: Securing the restricted zone around the leadership compound.

• Underground Bunker System: An extensive network of tunnels, shelters, offices, and storage areas designed to protect leadership during air raids and potential last-stand scenarios.

We think this is where Flo found or was given Hermann Göring’s armband and a Nazi flag that she saved in her album.

Current status: Much of the Obersalzberg complex was demolished after the war. Today, the site is home to the Dokumentationszentrum Obersalzberg, a research and educational museum focused on the history of Nazism and the regime’s use of the mountain retreat. The Eagle’s Nest still stands and is now a tourist site with panoramic views and a restaurant. The surviving bunker tunnels are accessible through the documentation center.

Ch. 71: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/11/15/ve-day-may-8-1945/