On Soyal Native Americans marked the shortest day of the year

My Regular Pagan Holiday Post: Winter Solstice

My queer family chooses to forgo holidays shaped by a christian tradition steeped in homophobia and misogyny—a church that has long covered up sexual abuse against children and parishioners while scapegoating queer people. Recent comments by Pope Francis only underline this contradiction, reaffirming the catholic church’s ban on ordaining gay men and punishing and defrocking priests who question that policy or support what it calls “gay culture.”

So we create our own rituals instead—queer, chosen-family–centered traditions. We look to other cultures for inspiration, especially pagan and pre-christian practices that honor the natural world and community rather than dogma.

We can learn much from Native Americans that might help us through what is shaping up to be a particularly dark period in our history and present.

Soyal: Winter Solstice and Renewal

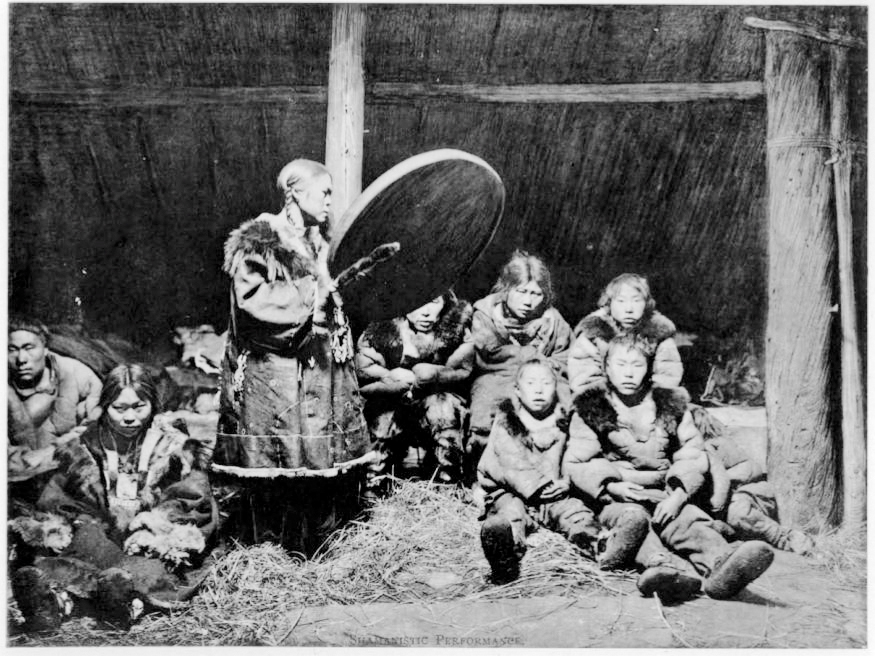

On the winter solstice, Hopi and Zuni peoples perform a ceremony with the intention of achieving unity and strengthening community. Soyal is held on the shortest day of the year. It marks the symbolic return of the sun, the turning of the seasonal wheel, and the beginning of a new spiritual cycle. Soyal is a time of purification, prayer, and renewal, when the community prepares itself—spiritually and socially—for the year ahead.

In the days before Soyal, families create pahos, prayer sticks made with feathers and plant fibers, which are used to bless homes, animals, fields, and the wider world. Sacred underground chambers, called kivas, are ritually opened to mark the beginning of the kachina season. The kachinas are understood as spiritual messengers who carry prayers for rain, health, balance, and right living. Songs, dances, offerings, and storytelling strengthen community bonds and pass ethical teachings from elders to children.

Soyal also dramatizes the struggle between darkness and light. Through symbolic dances and ritual objects, such as shields representing the sun and effigies symbolizing destructive forces, the community enacts the tension between chaos and order, drought and rain, winter and warmth. The message is not that darkness must be destroyed, but that it must be faced, respected, and brought back into balance.

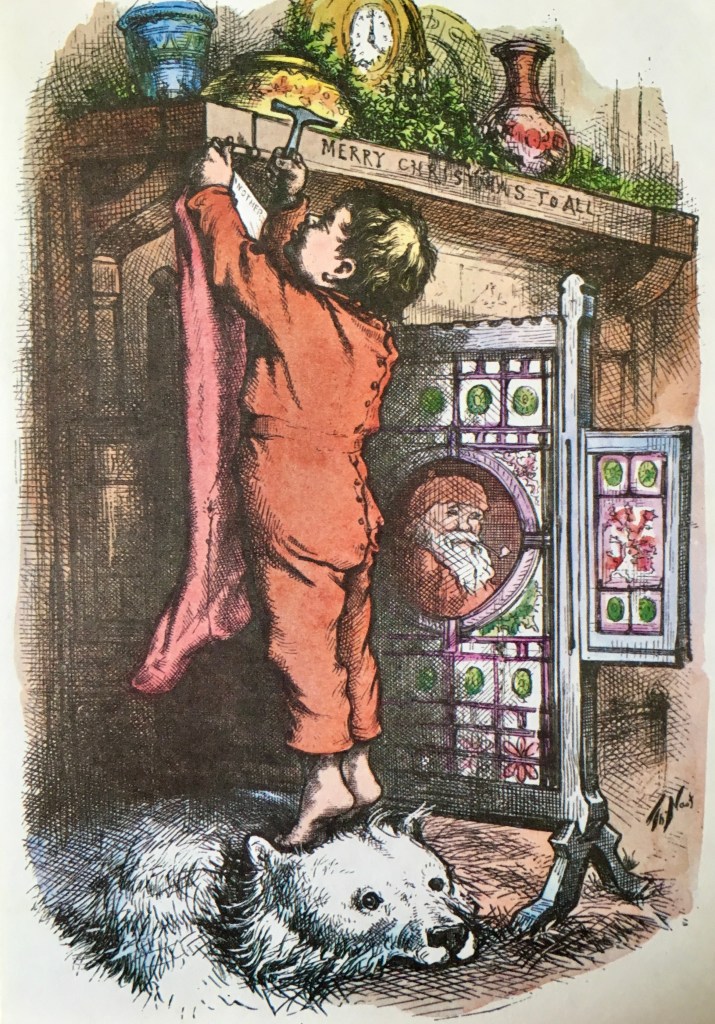

The solstice itself becomes a sacred pause: a moment when time feels suspended and people are invited to examine their lives. It is a season for letting go of harmful habits, reconciling conflicts, offering forgiveness, and setting intentions rooted in responsibility rather than personal gain. Gifts are exchanged not as possessions, but as blessings and goodwill.

Creating Our Own Rituals

Soyal reminds us that human life is meant to move in natural cycles, not endless acceleration. Rest is not weakness; it is a form of wisdom. Renewal begins with humility, gratitude, and shared responsibility. Personal healing is inseparable from the health of the community and the land.

The enduring spiritual mission expressed through Soyal is the same across Hopi villages: to promote and achieve the unity of everything in the universe.

While that vast unity may be beyond our vision, we, too, seek to strengthen our community and mark the return of light. At winter solstice, we gather ourselves and our loved ones, shaping rituals that keep us connected to one another and to the slow turning of the year. We invite friends to help us trim our solstice tree, contribute to the local food bank, have neighbors over for hot chocolate, read poetry and stories aloud, bake cannabis edibles, host impromptu living room dance parties, cook savory soups, plant flower bulbs. With neighbors, we make signs and join street protests to raise our voices against fascism. We look for the sacred in everyday life.

Happy solstice to all, however you celebrate!