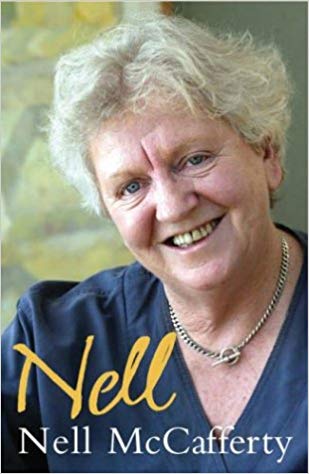

Pioneering Irish feminist and lesbian

Dear Nell McCafferty,

When I read your autobiography, I felt I just had to write you. Your recounting of the Irish feminist movement and the time of the Troubles informed and affected me greatly. Then I realized every old feminist, and especially lesbians, must feel the same. Have you received tons of mail from us since the book came out in 2005?

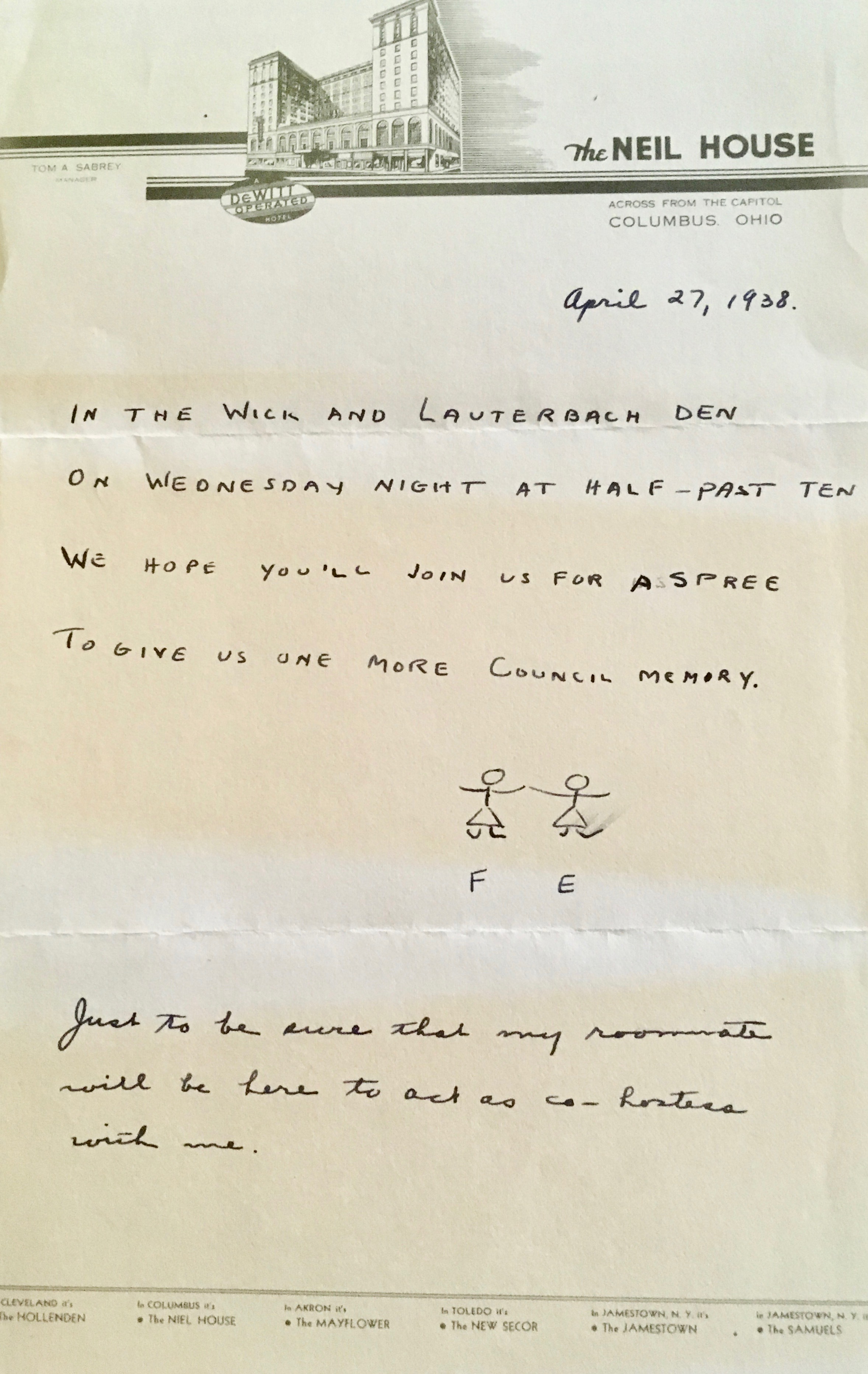

I confess that last month I had never heard of you, or at least I don’t remember if I did. Here’s how I got to your book. We have a little grrrl gang here in Santa Rosa, Sonoma County, California where I have just moved from San Francisco (about 60 miles away). We pass books around, and people in our neighborhoods have adopted the endearing custom of erecting mini-libraries, enclosures on posts rather like the old-style mailboxes only bigger and sometimes quite elaborate, painted bright colors with bells and birds and doors and windows. My block in this new-to-us neighborhood has such a library where anyone can leave a book or take a book to read. This is where we found a book by Nuala O’Faolain, the novel My Dream of You. I didn’t get far before I wikipedia’d her and found her life to be more interesting than her novel. So I ordered Are You Somebody? and read it. That’s when I discovered you. In the book she hardly mentions you and your 15-year relationship. What gives? So I wikipedia’d you and ordered your book Nell from the library. Funny thing, my library did not have it, nor did the San Francisco library. Had you been erased? Especially in San Francisco, a city with a large Irish population and some connections to IRA sympathizers, I would think your story would engage many readers. I can only guess at why your book may have been suppressed. Americans have a poor understanding of Irish history, or any history for that matter. Finally my wife, who does all the on-line ordering in our family, got your book. It is a used book with a lovely inscription on the flyleaf from one feminist to another.

Well, I should have heard of you! I’m an old lesbian feminist and a writer as well, though not famous by any means. But I’m a cog in that feminist wheel, as we all pulled together. As you were, I’ve been active in the struggle to legalize abortion, against sexual harassment and rape and all the other feminist issues, but my main focus has been to see to it that women can work at well-paying jobs. Paid work is the key to our independence and in the U.S. some of the best jobs are those reserved for men in the construction trades. I was a pioneer, one of the first women to get into the electrician trade, and I made a good career of it. I’m retired now and can look back on our decades of activism, our failures and successes with the hope of keeping the next generation from making the same mistakes. We call ourselves Tradeswomen.

At the moment, as you can imagine, I and my sisters are feeling pretty demoralized, though we are doing what we can to confront the ascent of what looks more and more like fascism. But reading your account of the Troubles and those hopeless years in Ireland helps me to imagine a light at the end of this tunnel. The images that stick in my head are of you standing next to and speaking to a lawmaker who is then assassinated, and of the woman, your neighbor, banging her garbage can in her yard—to warn of the cops—shot dead by them. I’ve never been good at remembering names but in my old age (I’m 69, born in 1949) I rely more than ever on visual images.

That you are five years older made a world of difference at the time when we both came of age. Things were changing so fast in those days (not to say they aren’t now) but the progress of the feminist movement was a defining factor. And we come from very different cultures. In American schools we at least had some sex education. The Catholic church was not so powerful (I was brought up Presbyterian and didn’t take long to embrace atheism). My mother had worked as a stenographer, called herself a career girl and didn’t marry till in her mid-thirties. Unlike in Ireland, that was a choice American women in her generation could make, though they were paid less than men and were laid off when they married. My mother was born in 1913. I was devastated when she died at the age of 70, as you were when your mother died at 89, but I do know it doesn’t matter how long or well our mothers have lived for us daughters to experience deep grief.

Coming out as lesbian in my 20s was not nearly so hard as it was for you. I read in one of the obits for Nuala that the reason you were angry about her book was that you didn’t want to come out as a lesbian to your mother. I was so glad you were finally able to come out to her before she died. I am the oldest of four and have a brother who is gay (one of three brothers). We had both come out to Mom before she died, but I wish I’d had more time to process with her. Her name was Florence, her parents were immigrants from Sweden and Norway. We discovered the feminist movement together and that and anti-war activism were central to our relationship in the decade before she died.

On my father’s side we are Irish. The Irish ancestor, Thomas Martin, is an enigma. He probably came over in the 1830s. We think he was from a Protestant family and likely illiterate. My wife Holly and I traveled to Ireland a couple of years ago with the American protest singer and radical Anne Feeney. I wasn’t able to discover more about my own Irish heritage but my brother is working at it and we may still learn where Thomas Martin came from.

I was grateful that in the book you were so candid about sex and love. Some of the couples issues you describe, like the difference between one partner who wants quiet and alone time and the other who wants the company of others at home are all too familiar. And lesbian bed death, LBD we call it, we struggle to overcome. Also, all the changes we go through as we age. Menopause is different for each of us! I felt lucky to live through it with an older lover before I started, but that was in the early 80s when we were just starting to talk about it to each other and there were finally books we could read.

About Nuala—I realize both of you held back writing about the other and your relationship but from all I read it seems she was trying too hard not to be a lesbian. After I read Are You Somebody? I didn’t like her very much. I thought some parts of the book were just name dropping. When I compare it to Nell and wonder why it didn’t strike me the same way, I think it’s because your story supplies context. Or perhaps your context was just more interesting. No, I think your book is just better. And I’m writing to tell you how much I enjoyed it and how much I learned from you. It’s a shame your book was not distributed more widely but be assured that you are famous here in this little corner of Northern California among our lesbian grrrl gang. Thank you for writing it.

Slainte,

Molly Martin