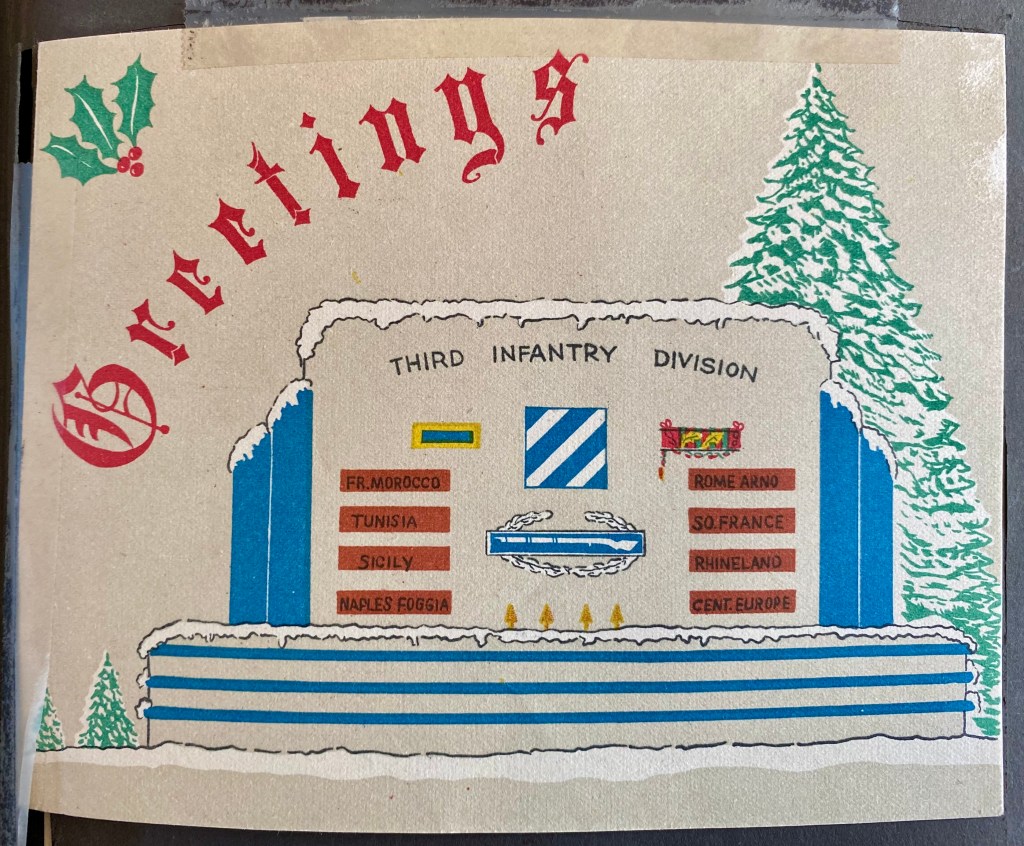

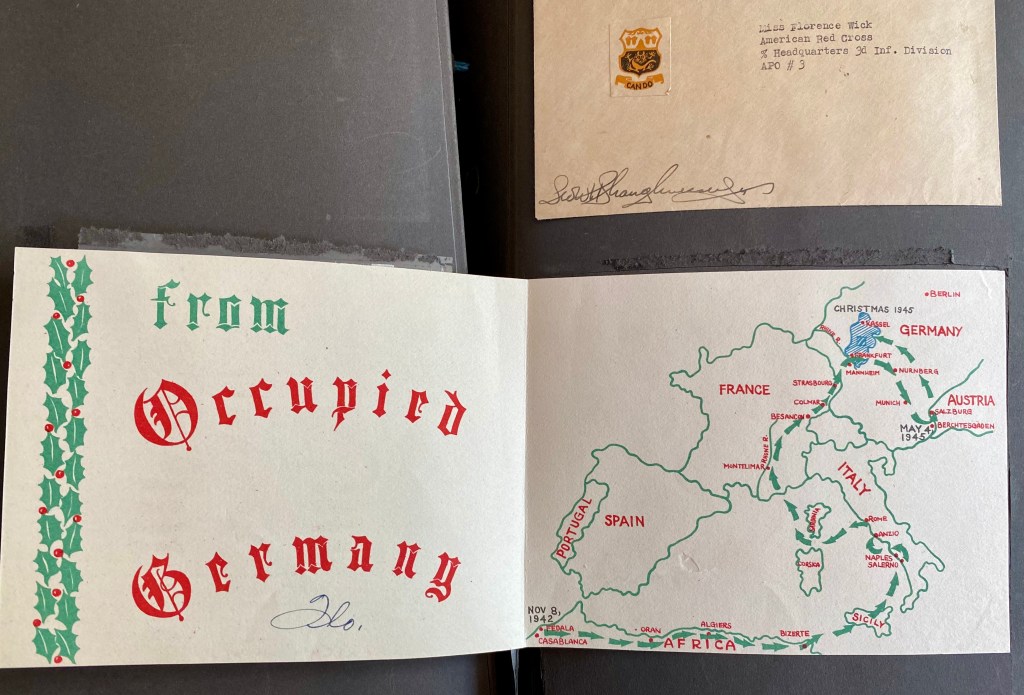

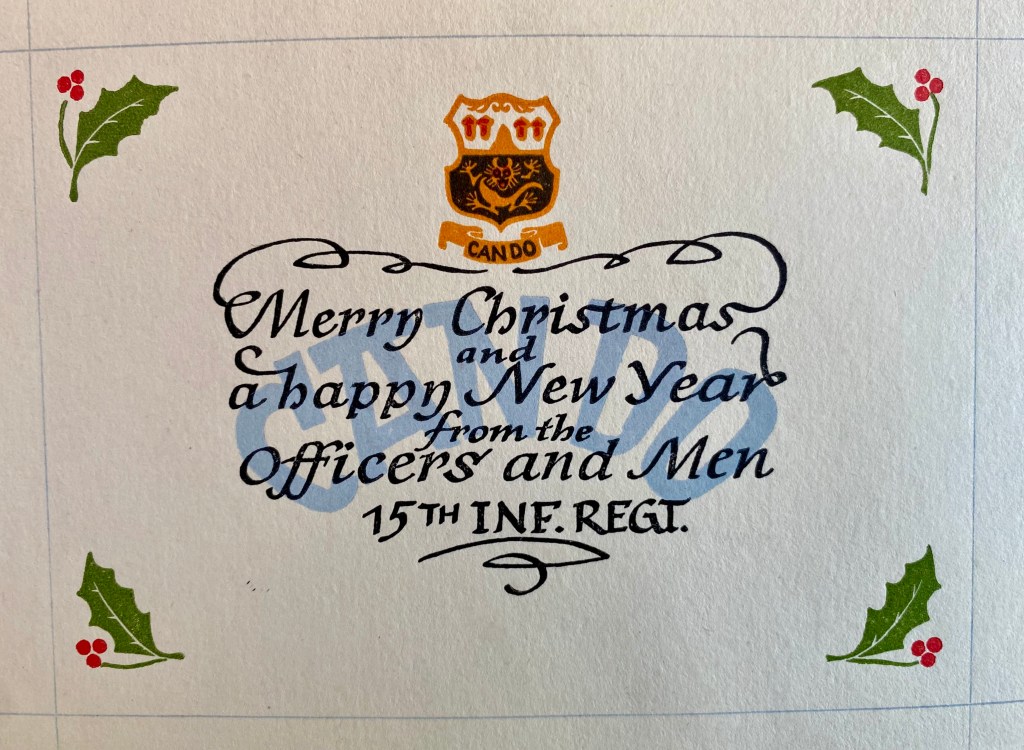

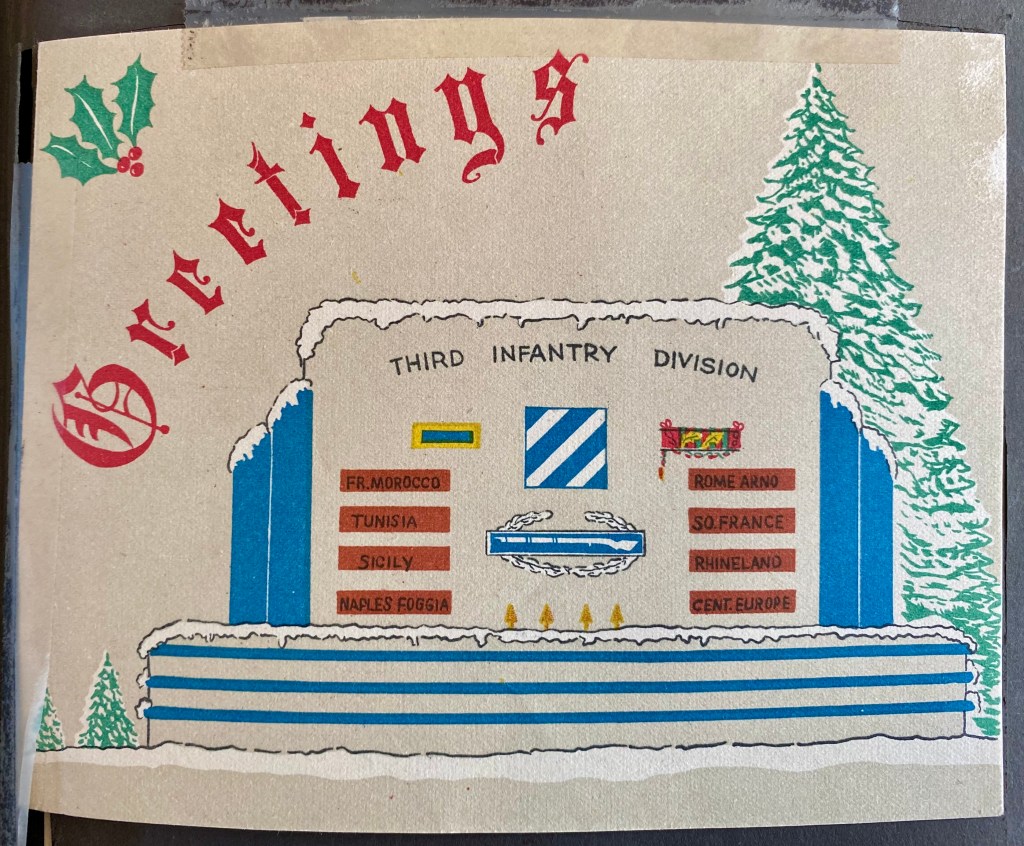

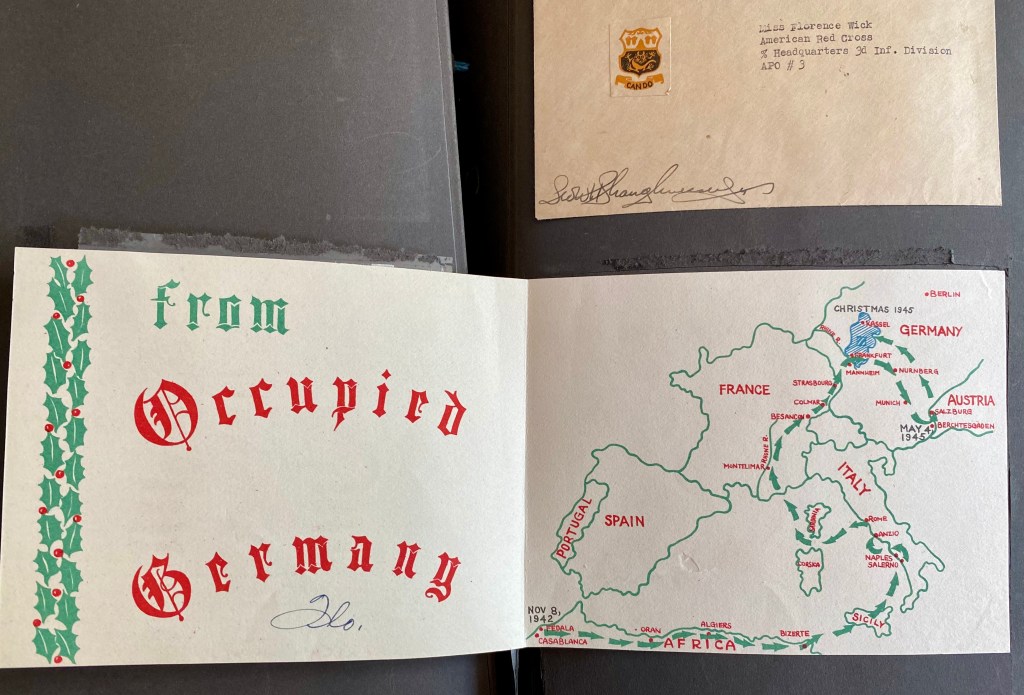

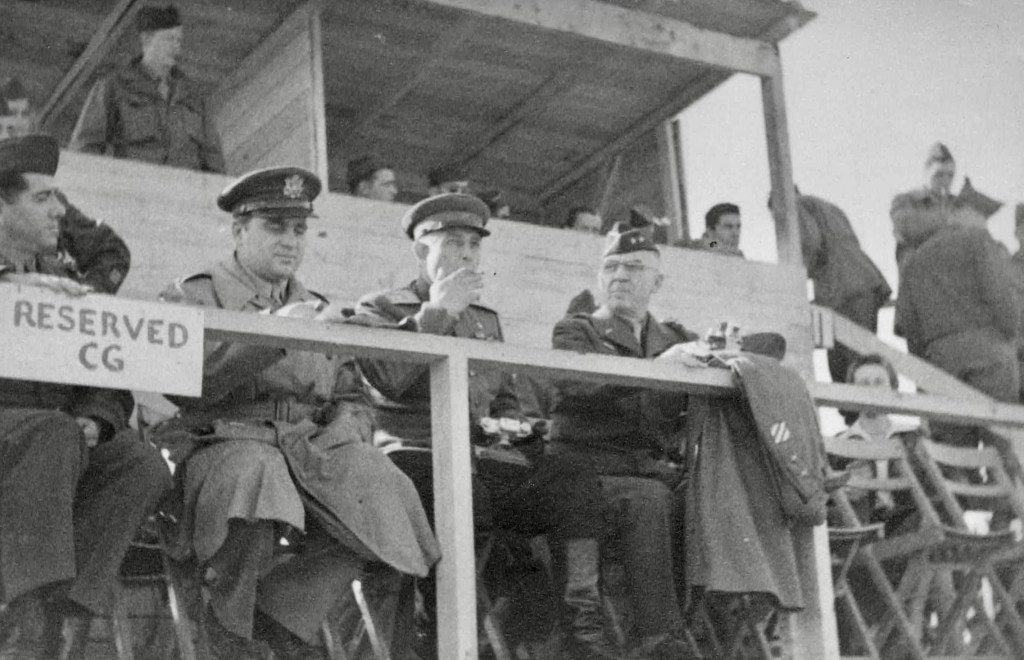

Gen. Schmidt’s New Year’s party celebrates Third Division

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 99

Ch. 100: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/03/03/front-line-publishes-special-edition/

Gen. Schmidt’s New Year’s party celebrates Third Division

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 99

Ch. 100: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/03/03/front-line-publishes-special-edition/

Flo and comrades get a look at the German capital

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 97

By the end of World War II, Berlin was no longer a city so much as a vast field of ruins. After enduring 363 air raids and a final, catastrophic ground assault, the German capital lay shattered—famously described by its own residents as a heap of rubble. Street by street, block by block, the urban fabric had been torn apart, leaving behind a landscape of collapsed buildings, twisted steel, and drifting ash.

Nearly 80 percent of Berlin’s city center had been destroyed. Across the wider metropolis, some 600,000 apartments were reduced to dust and broken brick. Infrastructure collapsed alongside homes: in the final days of fighting, 128 of the city’s 226 bridges were blown apart, a quarter of the subway system was deliberately flooded, and running water, electricity, and rail transport virtually ceased to function. Iconic landmarks suffered the same fate as ordinary neighborhoods. The Reichstag and Brandenburg Gate were battered by artillery and close-quarters combat, while along the grand boulevard Unter den Linden, only 16 of its 64 buildings remained standing.

The human cost was staggering. Civilian deaths from bombing raids alone are estimated at between 20,000 and 50,000. During the final Battle of Berlin, another 125,000 civilians are believed to have died amid the chaos of street fighting, shelling, and firestorms. At least 450,000 people were left homeless, and the city’s population collapsed from 4.3 million in 1939 to just 2.8 million by the war’s end—a mass exodus of refugees, evacuees, and the dead.

Unlike many cities that later erased the physical traces of war, Berlin chose to preserve parts of its devastation as visible memory. Bullet holes and shrapnel scars still mark walls in districts like Mitte and Charlottenburg. The shattered spire of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church stands deliberately unrepaired, a permanent anti-war monument rising from the city center. Elsewhere, mountains of rubble were piled into artificial hills—Teufelsberg and Volkspark Humboldthain—turning the wreckage of war into silent landmarks.

These images of destruction are not only records of ruin. They are reminders of the scale of collapse, the human suffering beneath the debris, and the deliberate choice to remember, rather than forget, what war reduced Berlin to in 1945.

Ch. 98: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/02/23/parachute-regiment-throws-a-party/

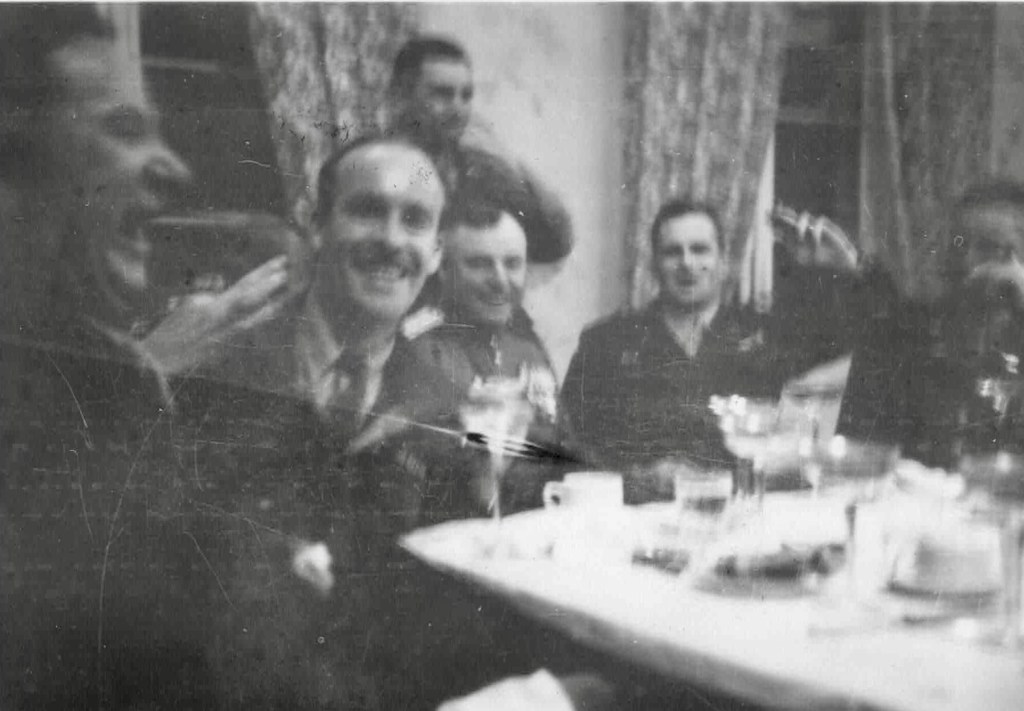

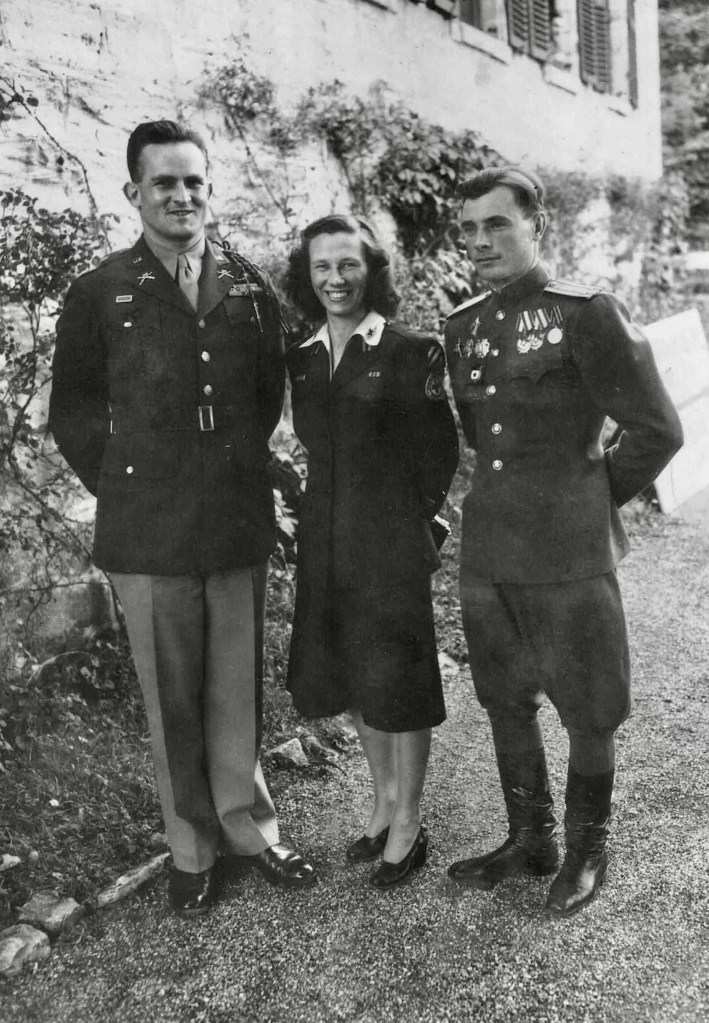

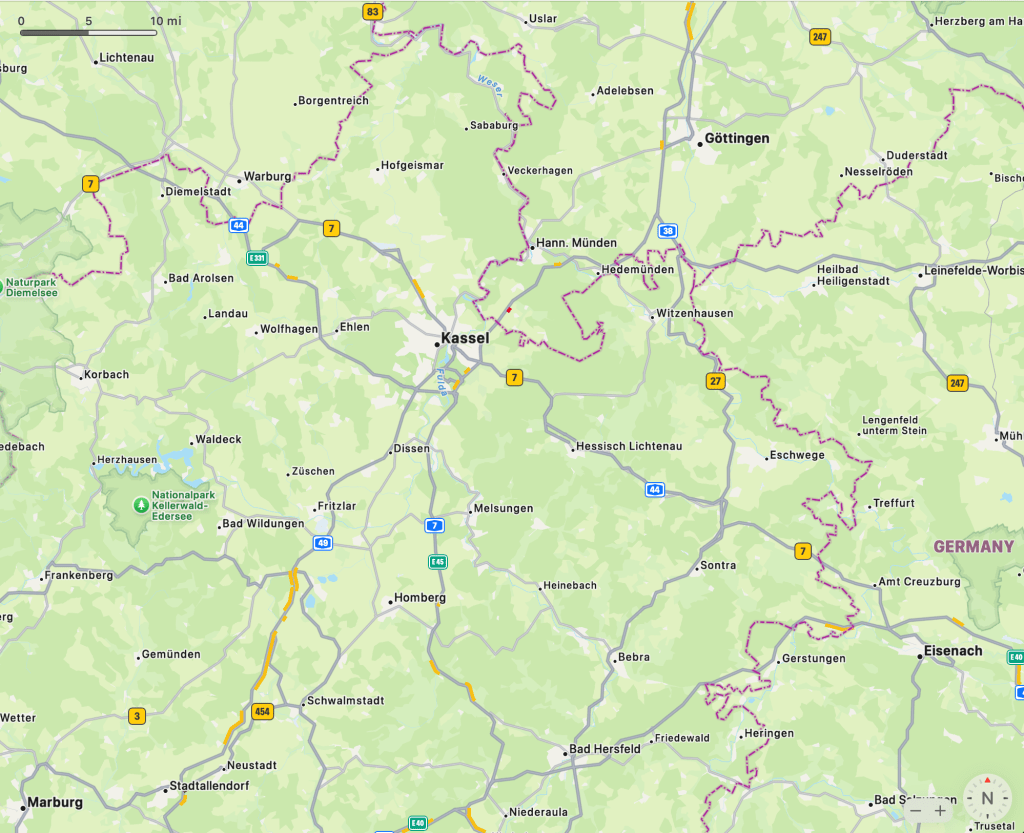

The gathering took place in Kassel, Germany near the border between Soviet and U.S. occupation zones.

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 94

Ch. 95: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/02/11/cagney-picks-up-murphy/

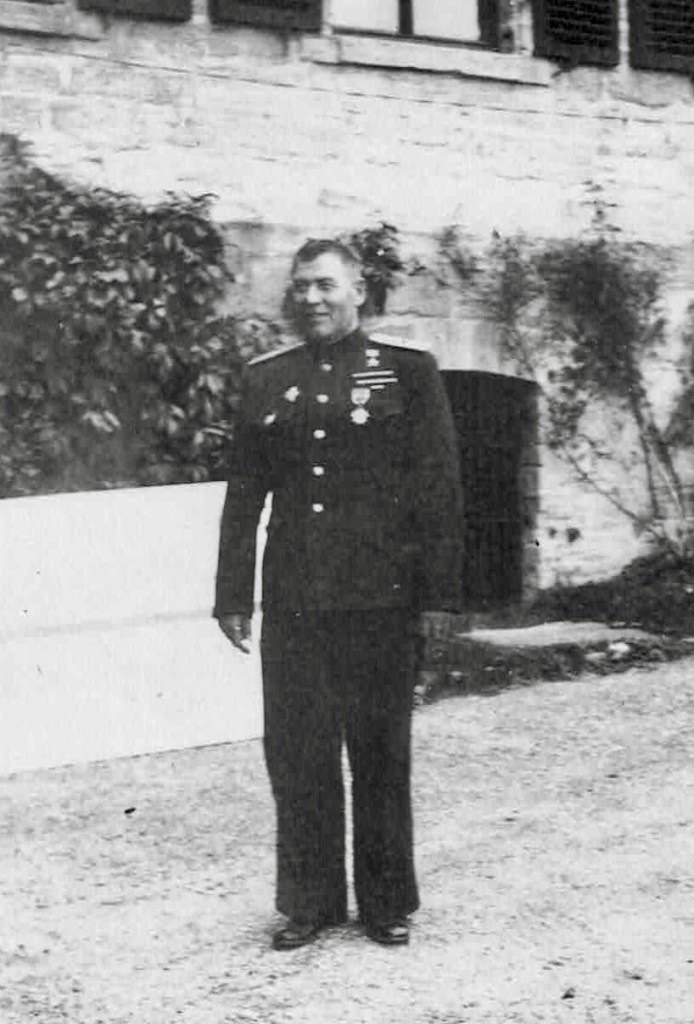

The agreement marked a territorial change in the occupied zones

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 93

Flo attended the historic Russian–American conference in Wanfried, Germany, where the Wanfried Agreement was signed on September 17, 1945. The agreement was a post–World War II territorial exchange between U.S. and Soviet occupation authorities, finalized in English and Russian, to resolve a logistical problem along the Bebra–Göttingen railway. A roughly 2.7-mile stretch of this crucial rail line briefly crossed into the Soviet zone near Wanfried, disrupting traffic vital to U.S. connections between southern Germany and the American-controlled port of Bremerhaven. To secure uninterrupted U.S. control of the line, two villages in Soviet-occupied Thuringia were exchanged for five villages in American-occupied Hesse. The agreement, informally known as the “Whisky-Vodka Line,” stands out as a rare, peaceful, and highly localized negotiation between the two superpowers in the tense early months of the occupation.

Ch. 94: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/02/07/english-americans-russians-party/

Remembering That the World Is Alive

My Regular Pagan Holiday Post

“During Losar, the Tibetan celebration of the New Year, we did not drink champagne. Instead, we went to the local spring to offer gratitude. We made offerings to the nagas, the water beings who awaken and sustain the water element in that place. We made smoke offerings to the spirits of the surrounding land. Beliefs and practices like these arose long ago and are often dismissed in the West as primitive. But they are not projections of fear onto nature. They come from direct, lived experience—by sages and ordinary people alike—of the sacred presence of the elements within us and around us. These we call earth, water, fire, air, and space.”

— Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche, Bon lama

The pagan holiday of Imbolc coincides with Losar, the Tibetan New Year—an observance older than Buddhism itself and rooted in Tibet’s indigenous relationship with land, weather, animals, and time. Losar’s rituals arose before Indian and Chinese influence, shaped instead by mountains, winds, springs, and the deep listening of people who understood the world as alive.

Losar is celebrated according to the Tibetan lunisolar calendar, which follows both moon and sun and adjusts itself to the breathing of the seasons. Months are added when necessary so that time does not drift away from frost, thaw, planting, and return. The calendar has a sixty-year cycle weaving twelve animals with five elements—Wood, Fire, Earth, Iron, and Water—each year a particular conversation between forces. In February 2026, Losar begins the Female Fire Horse year (2153), a year of movement, heat, and untamed momentum. The festival lasts fifteen days, with the first three devoted to renewal, protection, and blessing.

Before the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950, Losar opened with dawn ceremonies at Namgyal Monastery, where the Dalai Lama and senior lamas made offerings to Palden Lhamo, fierce guardian of the land and the Dharma. After exile and occupation, monasteries were destroyed and public ritual suppressed. Yet Losar did not disappear. It moved into exile, into kitchens and courtyards, into memory and breath. In Dharamsala, the Dalai Lama continues to offer blessings, while Tibetans everywhere keep faith with the spirits of place—even when the place itself is inaccessible.

How do we observe Imbolc?

By remembering that the world is alive—and responding accordingly.

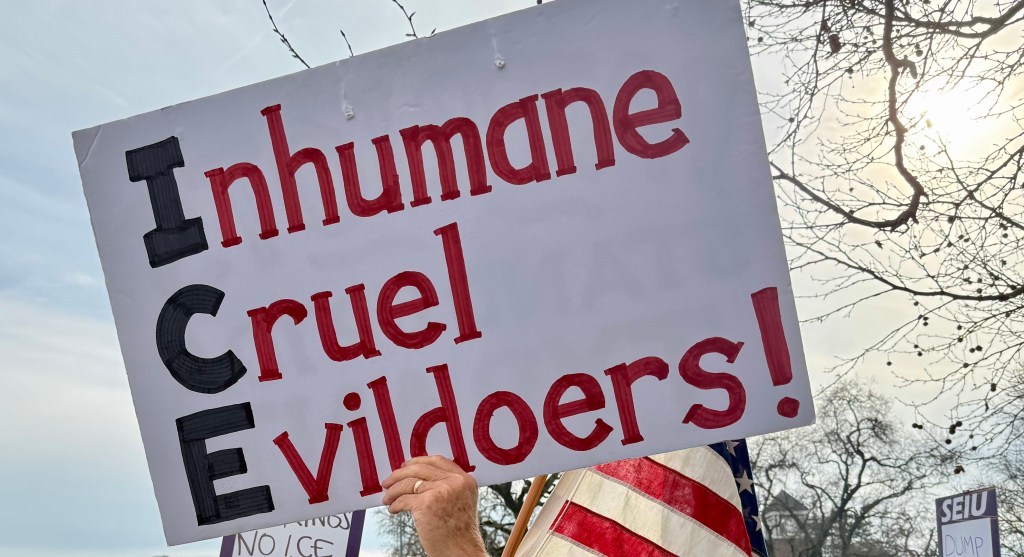

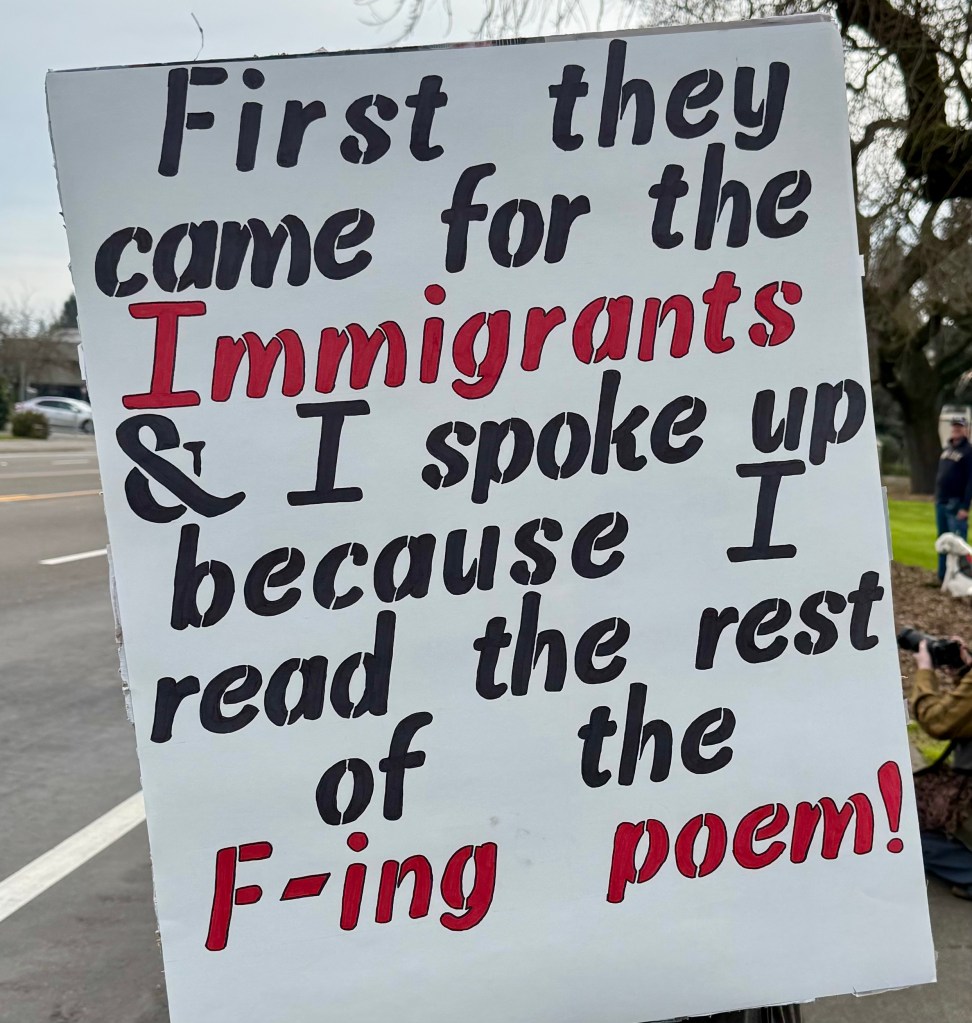

As we witness the brutal ICE raids in Minnesota, we feel the rupture in the web of relations. Bodies are dragged from homes; families are torn from their ecosystems of care, citizens are murdered. ICE has been run out of Maine where it targeted Somali communities after arresting 200 people and sending them to concentration camps. These acts violate not only the Constitution but the deeper laws of reciprocity that make life possible.

So we act.

We speak to our representatives and demand the defunding of ICE.

We write postcards, calling neighbors back into civic responsibility.

We organize to protect our town if the violence arrives here. The North Bay Rapid Response Network provides a 24-hour hotline to immigrants facing a raid by federal immigration agents, dispatches trained legal observers to the raid location, provides legal defense to affected communities, and offers accompaniment to impacted people and families following a raid.

We protest, along with our community and neighbors.

We put loving kindness out in all directions for the benefit of all beings.

And we plan our gardens for the coming year—because tending soil, saving seed, and preparing for planting are acts of allegiance to life itself.

Resistance, like ritual, is a way of keeping faith with the land, the waters, and one another.

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 92

Witzenhausen, Germany, lay within the American occupation zone near the border with the Soviet zone, making it strategically important for intelligence and personnel transfers. In 1945, U.S. forces used the town during Operation Paperclip to evacuate German rocket scientists, including Wernher von Braun, from Bleicherode to prevent their capture by advancing Soviet troops, underscoring Witzenhausen’s role in the emerging Cold War. The town became a U.S. Army garrison, with military bases integrated into local life, a pattern seen across West Germany. This long American presence left lasting marks on language, consumer culture, and infrastructure, making Witzenhausen a microcosm of the broader U.S. occupation experience.

Ch. 93: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/02/03/the-us-and-ussr-sign-a-peaceful-pact/

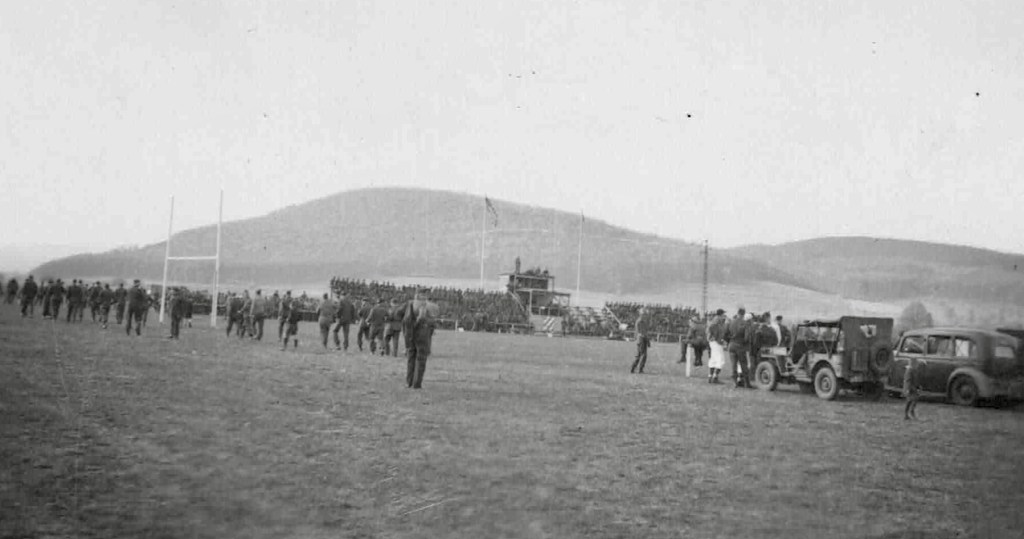

Third Division vs. 29th

Ch. 91 My Mother and Audie Murphy

The football games were part of a sports program organized to occupy restless American and Canadian troops awaiting discharge. In August 1945, the U.S. Army had staged the “GI Olympics” in Nuremberg, with high-ranking Russian observers in attendance. Events included a baseball game played in the former Hitler Youth Stadium—an unmistakably symbolic reclaiming of Nazi space. That same day, news of Japan’s surrender crackled over the loudspeakers, unleashing a roar that seemed to lift the roof as GIs tossed caps, coats, and red-white-and-blue programs into the air, hugging, kissing, and celebrating the war’s end. The festivities continued into the night with performances by Hal McIntyre at the amphitheater and Bob Hope at the Opera House, drawing thousands of cheering troops in a city freshly transformed from fascist spectacle to victorious release.

Ch. 92: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/01/30/around-witzenhausen-autumn-1945/

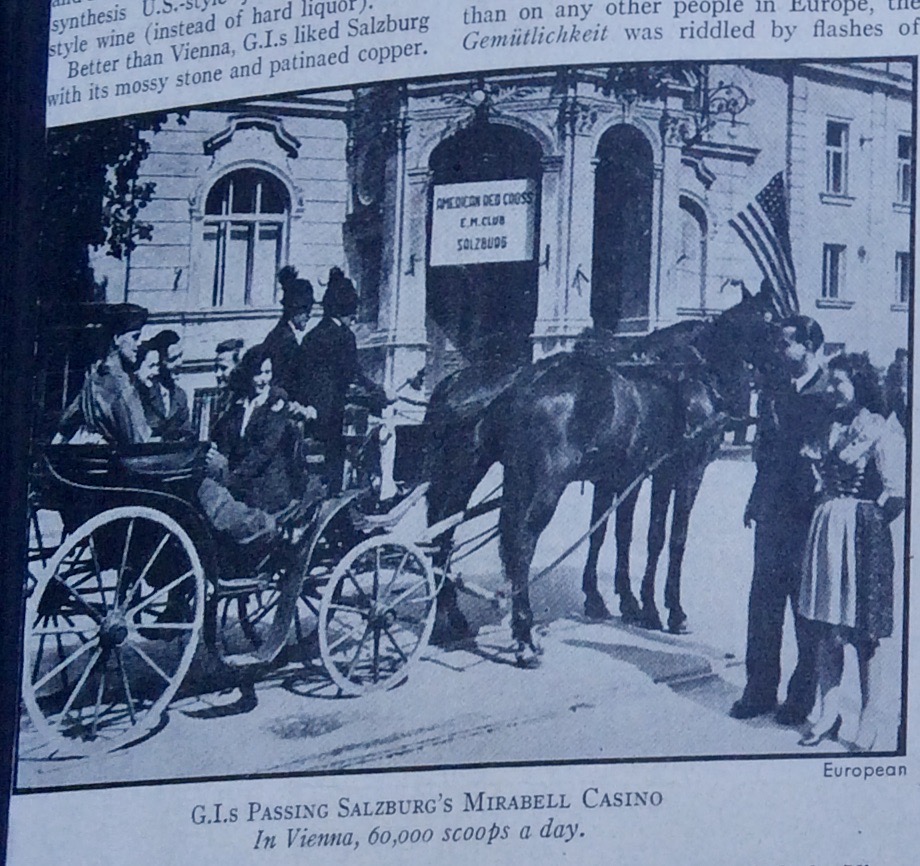

The Geműtlichkeit was riddled by flashes of bitterness

Ch. 88 My Mother and Audie Murphy

Flo pasted this page from an English language newspaper in her album. The story gives more details about what it was like for Americans and Austrians alike during the occupation. It mentions that the Red Cross had a club in the Mirabell casino in Salzburg and it’s a good bet Flo spent time there. She may have had to work serving coffee and donuts there.

Ice cream and jitterbugging

(In Vienna the Army) set up replicas of US drugstores where GI’s could take their Austrian girls for a soda (daily ice cream consumption of the US army and friends in Vienna now runs to 60,000 scoops.) Among venerable establishments, Broadwayish nightclubs sprouted. Racily named Esquire, Zebra, and Heideho, they offered in neat, cultural synthesis US style jazz and Viennese style wine instead of hard liquor.

Better than Vienna, GI’s liked Salzburg with its mossy stone and patinated copper. The Red Cross had moved into the Mirabell casino and the GI’s listened to symphony concerts in the Mirabell castle’s gardens. Then, oblivious to the echoes of Mozart’s minuets, they jitterbugged in the old, staid Hotel Pitter….

Nearby, built directly against the rough mountainside, was the Festspielhaus, through whose cavernous yard had boomed the theatrical damnation of Dr. Faust. The GI metamorphosis had turned it into a movie house nostalgically named the Roxy. And around Salzburg’s Bierjodelgasse (beer-yodel street) GI’s noisily scouted for beer gardens.

The favorite outdoor sport was chamois hunting in the mountains hovering over the city–where the game poacher has always been a highly respected member of society, and where one of Austria’s most important bits of national philosophy originated: If you hadn’t climbed up you wouldn’t have fallen down.

Krauts and cokes

Although Americans had made a better impression on Austrians than any other people in Europe, the Geműtlichkeit (good feeling) was riddled by flashes of bitterness. Usually broad minded, the Viennese grew jealous, called girls who fraternized with the chocolate-bearing GI’s “chocoladies.” The sprinkling (5%) of combat veterans among US troops called the Austrians just plain krauts only softer.

Last month soldiers in the US zone were booked for 32 assaults, 5 rapes, 3 disorderly conducts, and one house breaking. Cracked an MP officer: “Now that we’re getting quantity supplies of Coca-Cola maybe our boys will get back to behaving.” But most GI’s in Austria already had passing marks for behavior; and many were living up to their orientation slogan, “Soldier, you are helping Austria.” The first crop of Austrian babies fathered by helpful GI’s is sizable.

Ch. 89: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/01/18/report-on-the-occupation/

Traveling Around the American Occupation Zone

Ch. 87 My Mother and Audie Murphy

Kassel, Germany, was a critical WWII target due to its Henschel & Sohn factories (building tanks like Tigers and Panthers) and major railway hub. The city suffered devastating Allied bombing from 1942-1945, especially the October 1943 raid that destroyed the city center and killed thousands. Few inhabitants were left by the time US forces captured it in April 1945 after intense fighting, concluding a brutal chapter of destruction. The Third Infantry Division was heavily involved in the fight for Kassel before securing the region, and later established its command structure in the surrounding Hesse area.

From pictures on this page of her album, it appears Flo was able to travel around the Hesse area as a tourist. She was probably continuing to dish out donuts to occupation troops from the clubmobile.

Ch. 88: https://mollymartin.blog/2026/01/15/austria-during-american-occupation/