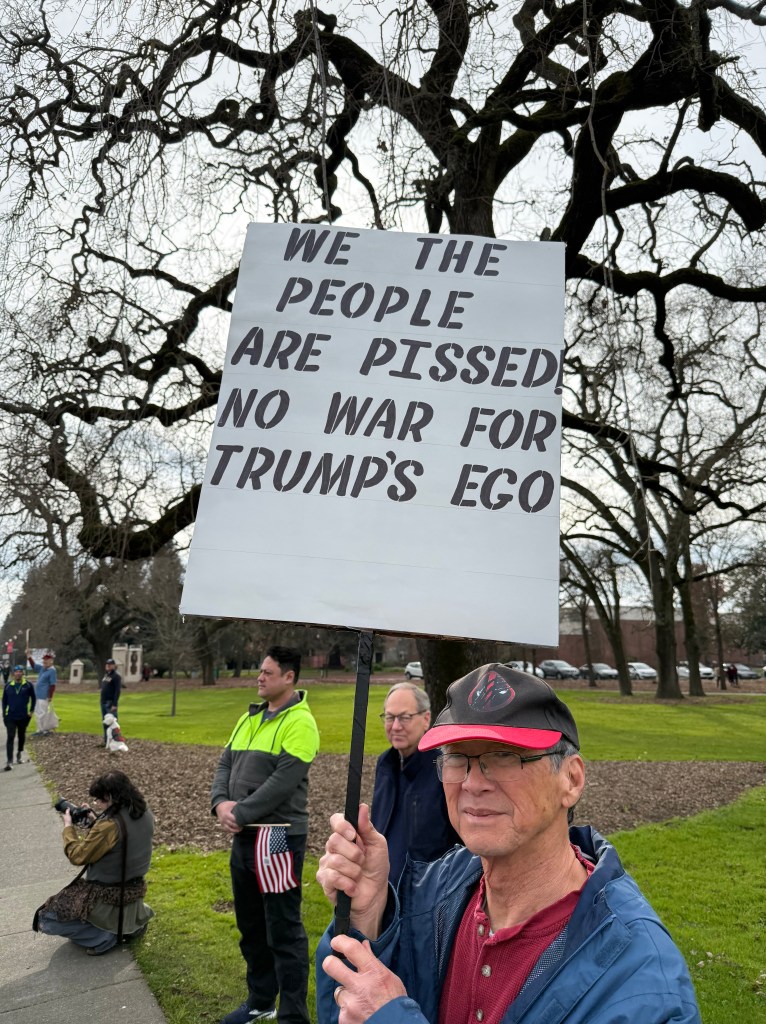

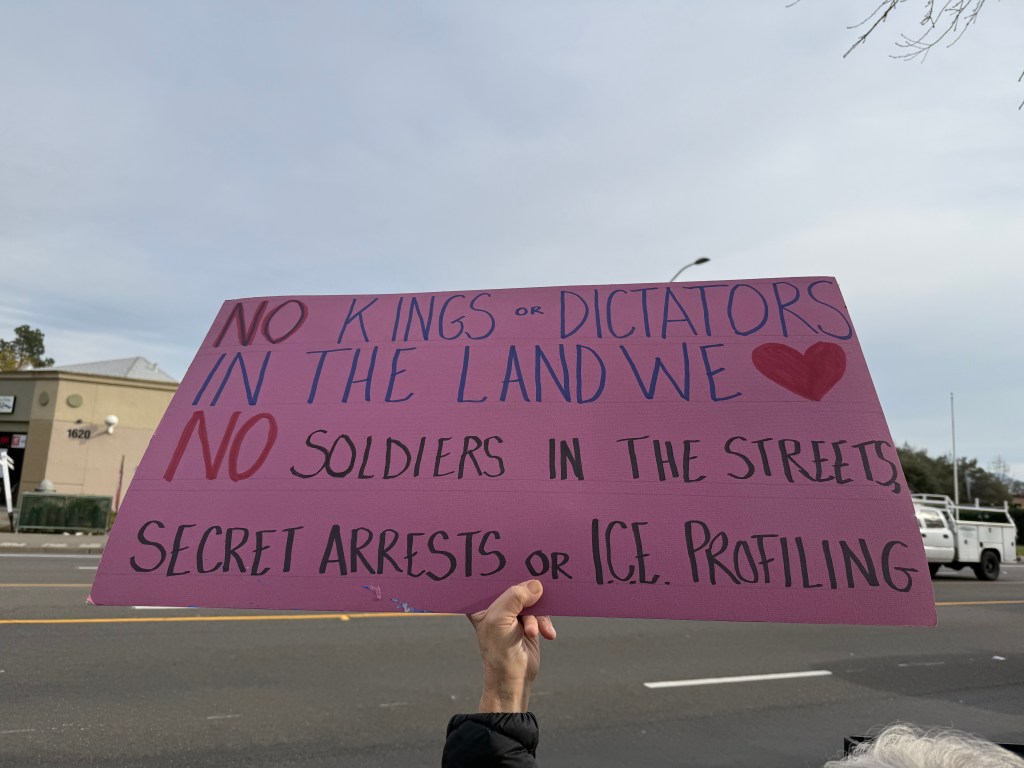

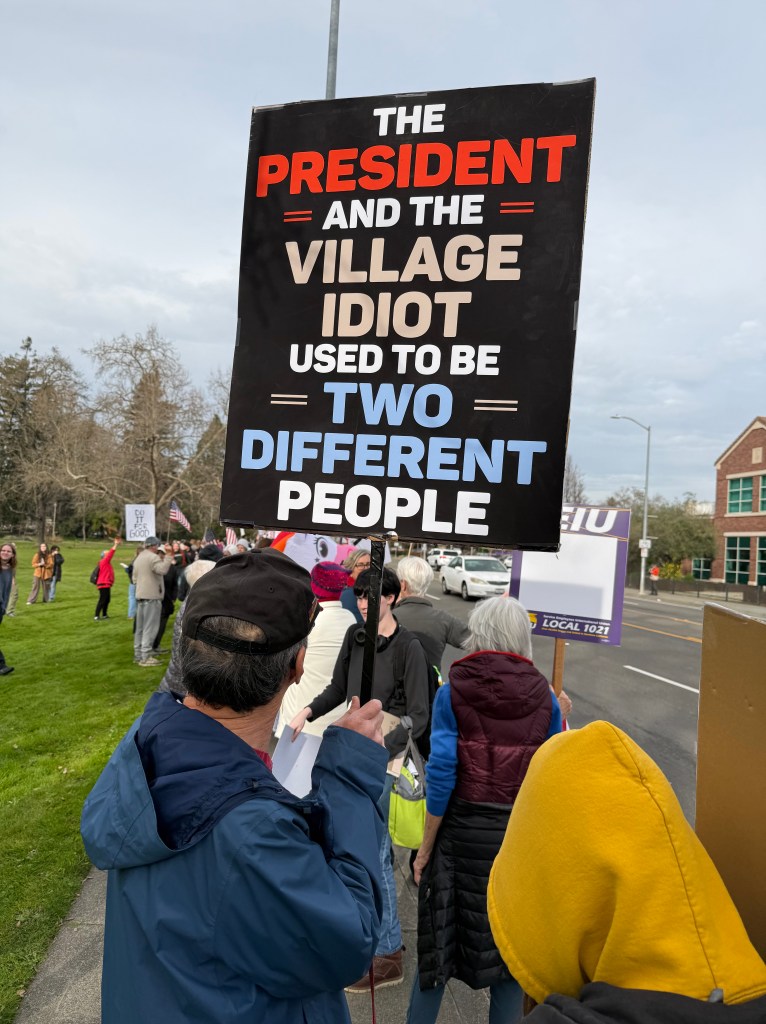

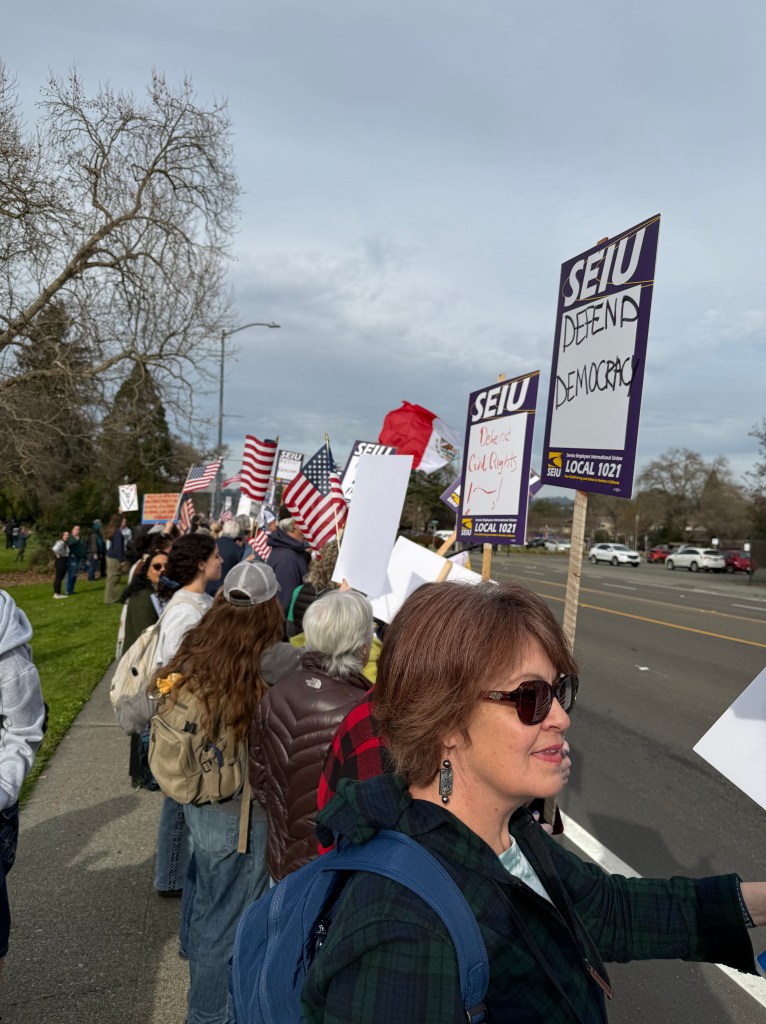

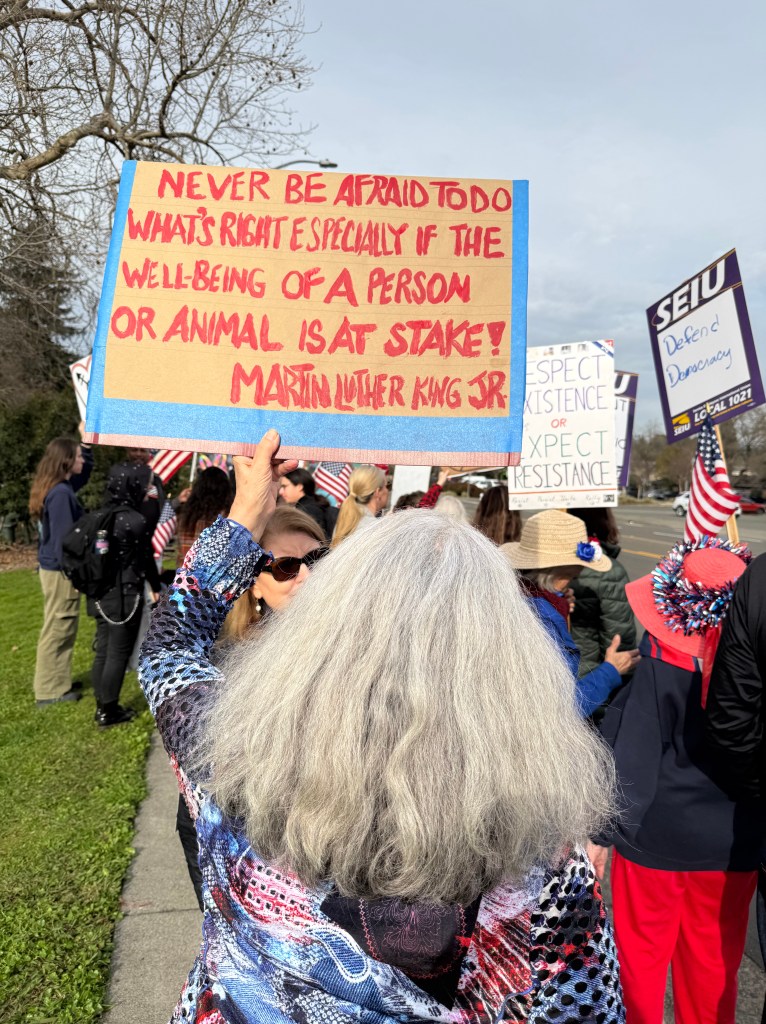

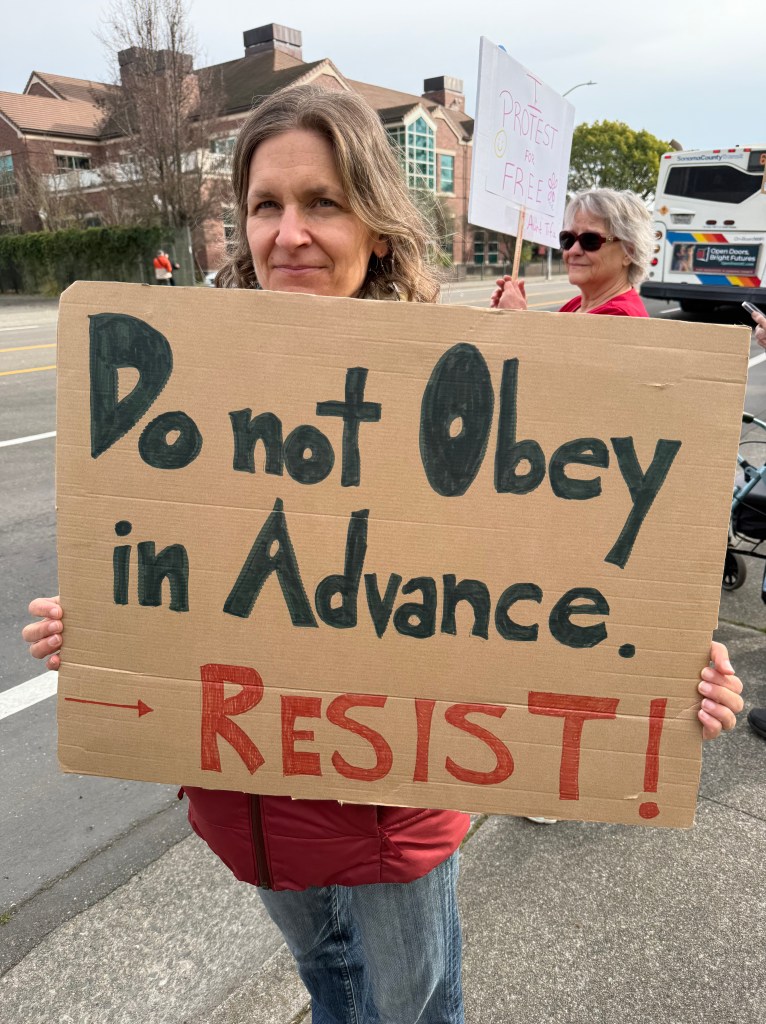

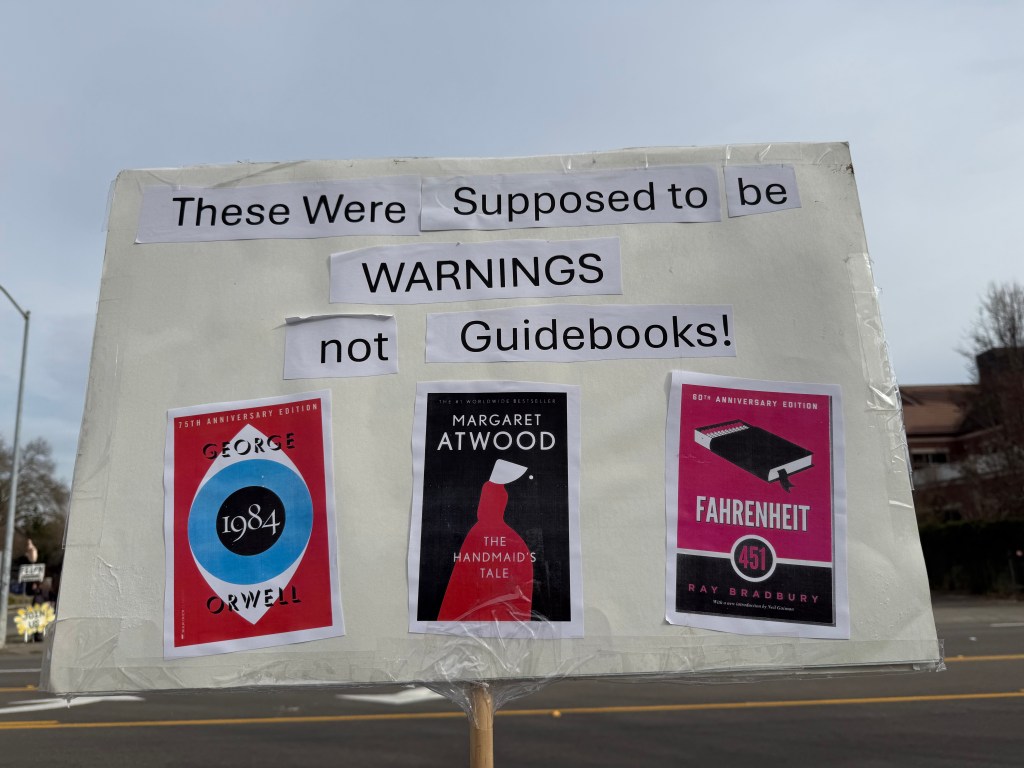

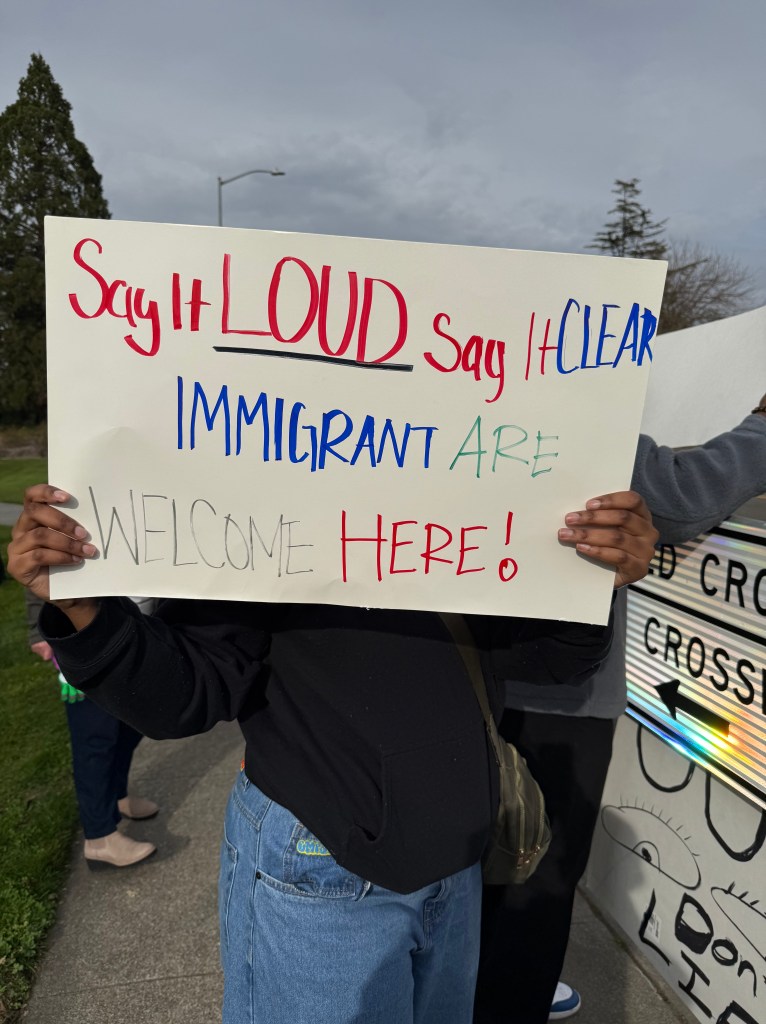

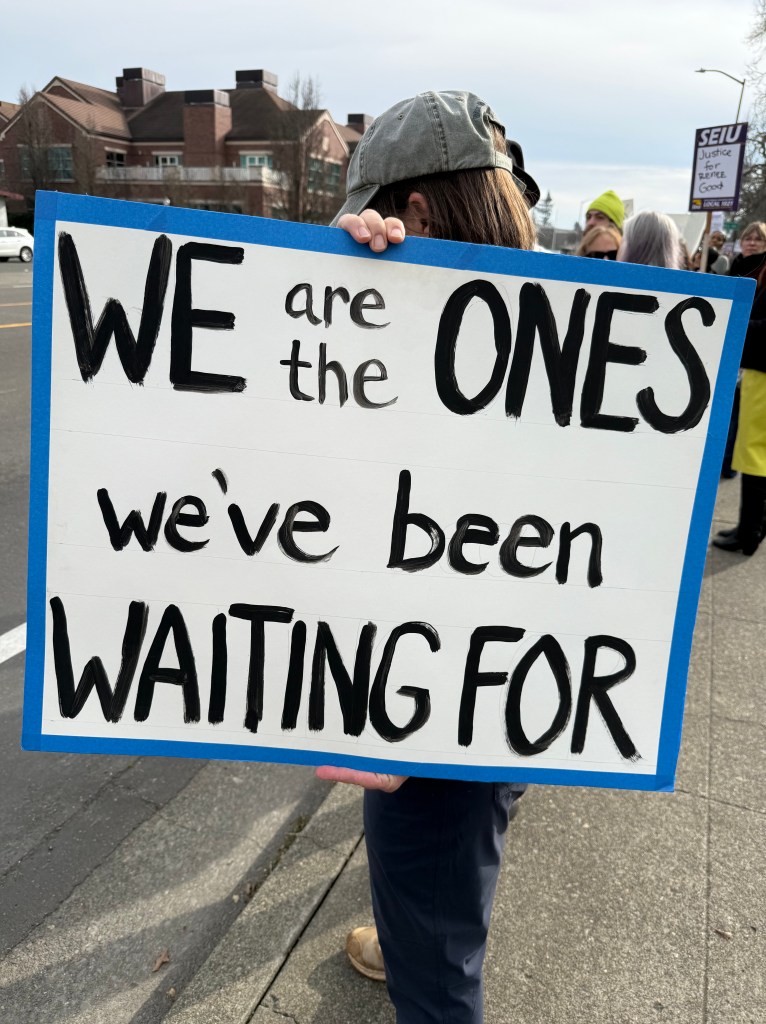

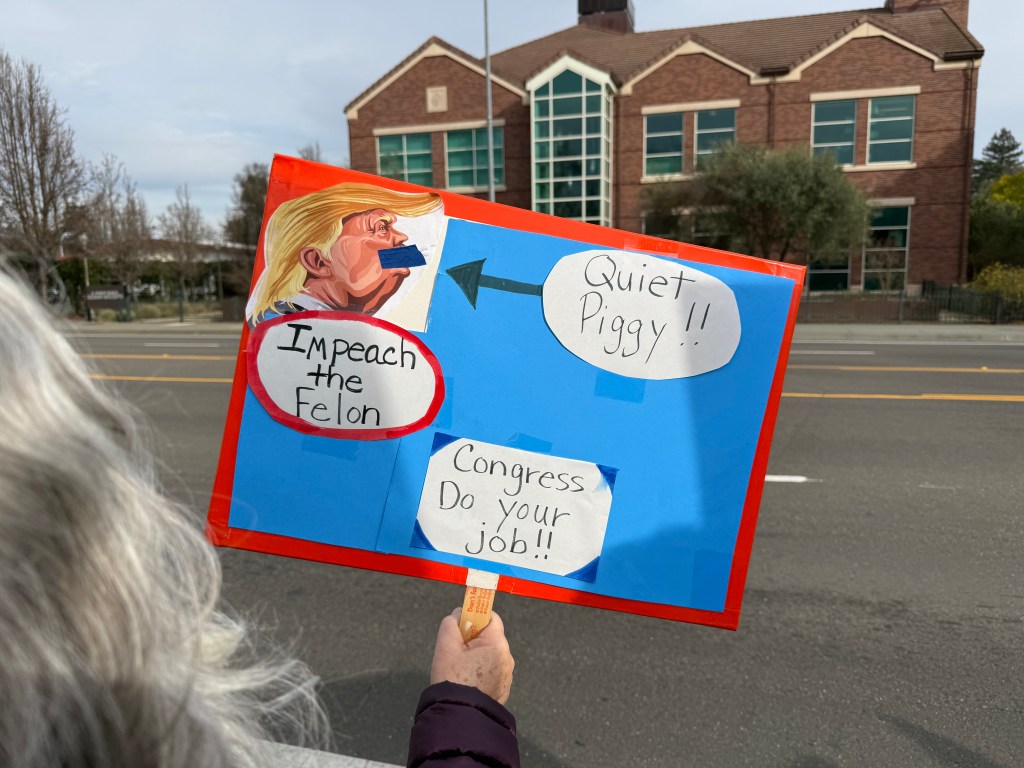

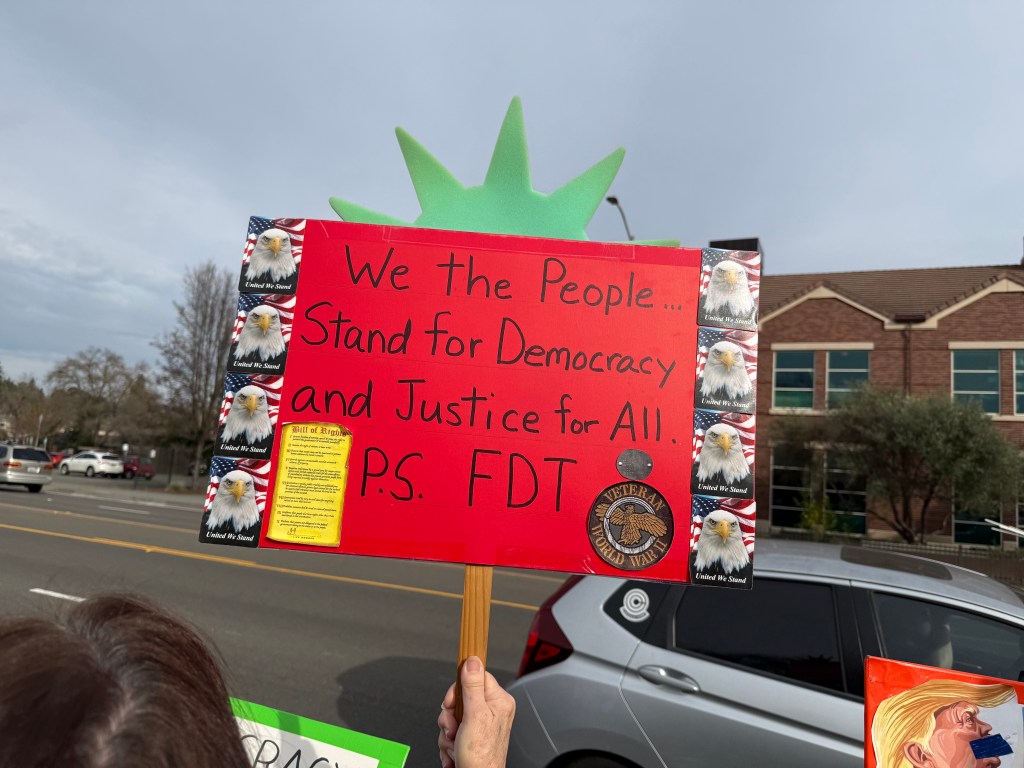

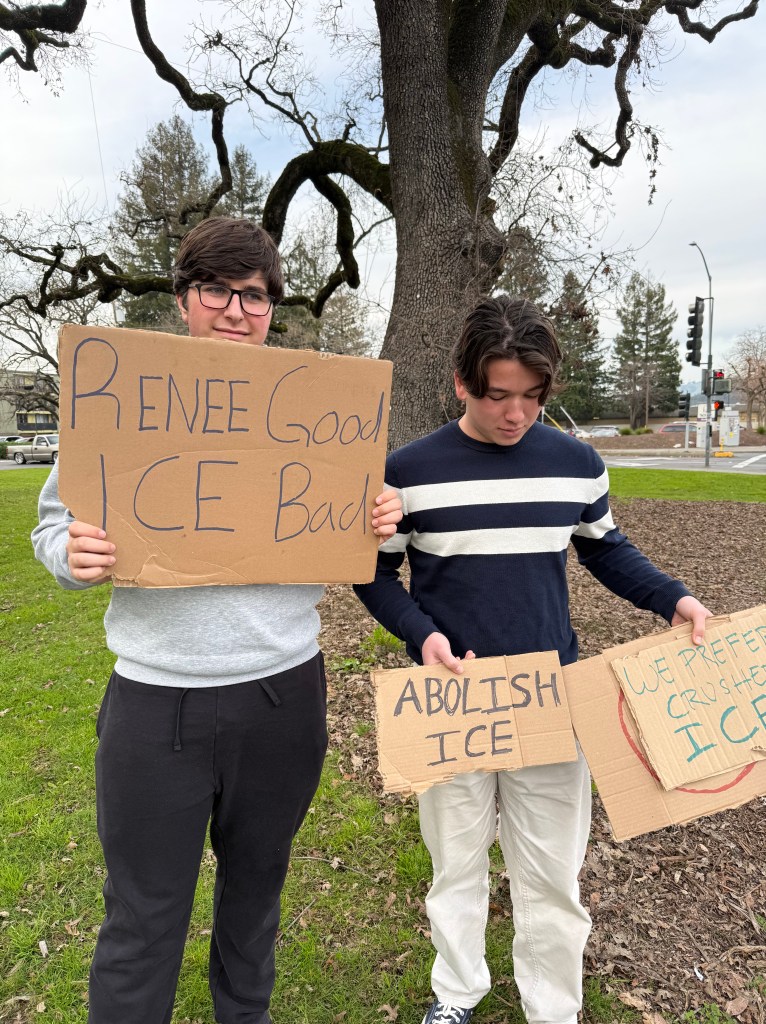

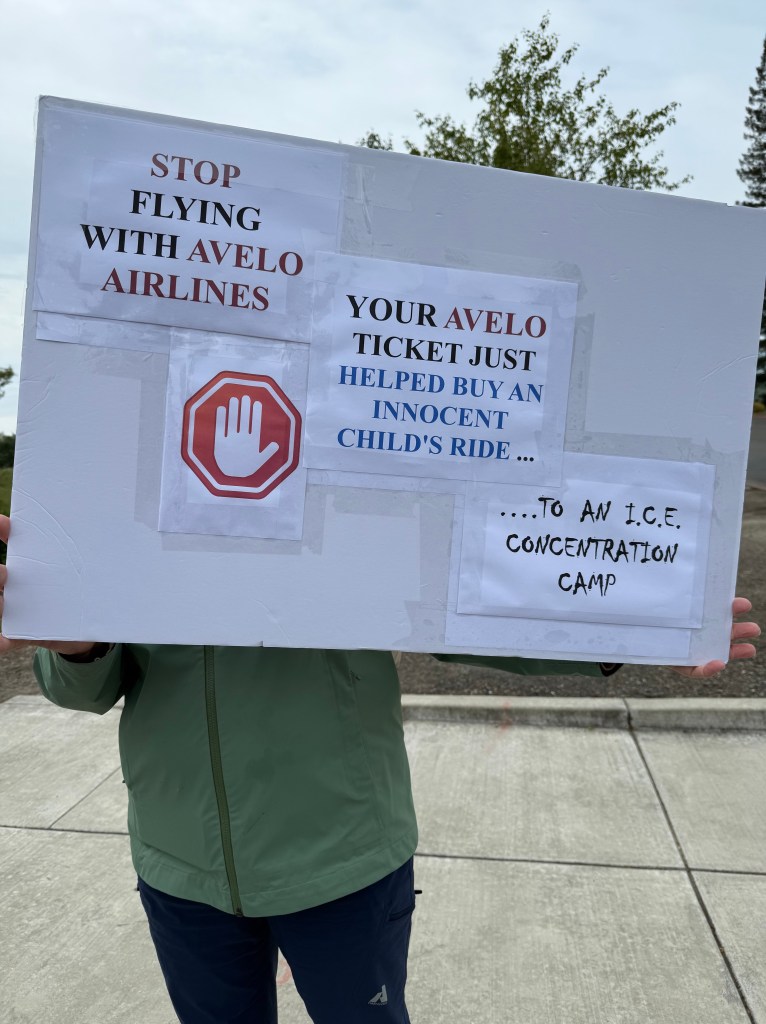

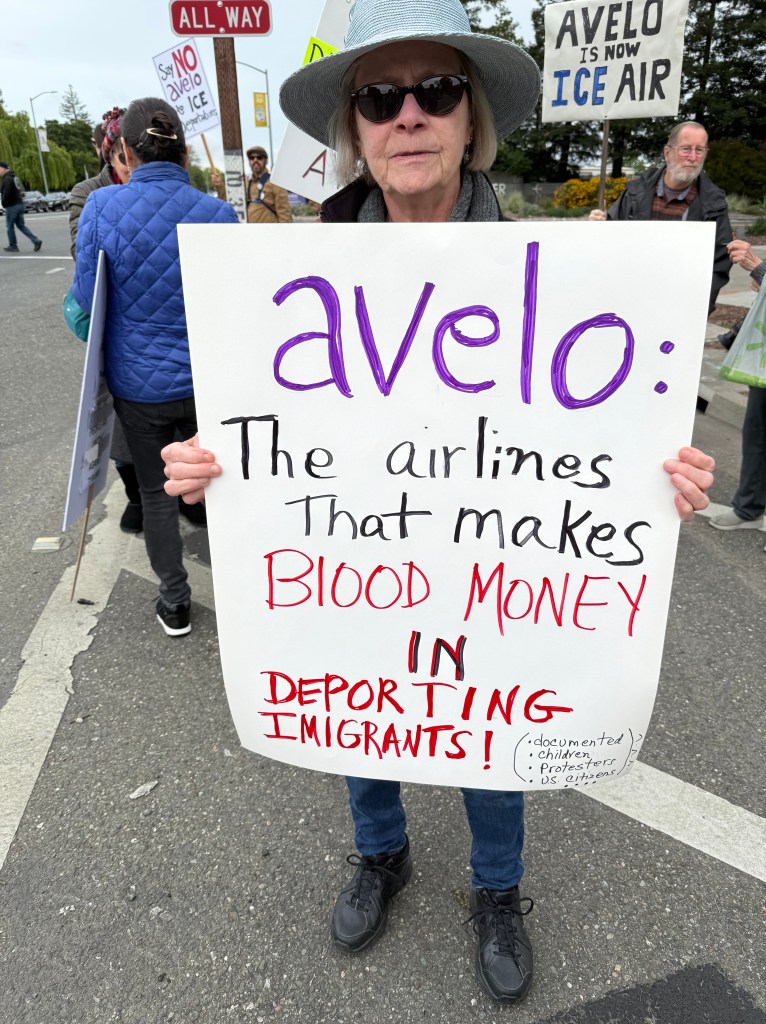

With Santa Rosa Women’s March and SEIU Local 2021

Folks Get Creative With Their Signs

Tradeswomen Reject Union’s Capitulation

Tradeswomn Inc. is a nonprofit I helped found in 1979. Still going strong, the organization helps women find jobs in the union construction trades. Here’s the text of a speech I gave October 30, 2025 at Tradeswomen’s annual fundraising event.

Sisters, we’ve come a long way.

When we first started Tradeswomen Inc., we had one goal:

to improve the lives of women — especially women heading households —by opening doors to good, high-paying union jobs.

It took us decades to be accepted by our unions.

Decades of proving ourselves on the job, standing our ground, demanding a seat at the table.

And now — by and large — we’re there.

We are leaders. Business agents. Organizers. Stewards.

We have changed the face of the labor movement.

But sisters, we are living in a dangerous time.

Our own federal government is attacking the labor movement.

And we cannot look away.

We all know that Donald Trump is gunning for unions.

Project 2025 is his blueprint — a plan to dismantle workers’ rights and roll back decades of progress.

Let me tell you some of what’s in that plan.

It would roll back affirmative action, regulations we worked so hard to secure,

Allow states to ban unions in the private sector,

Make it easier for corporations to fire workers who organize,

And even let employers toss out unions that already have contracts in place.

It would eliminate overtime protections,

Ignore the minimum wage,

End merit-based hiring in government so Trump can pack the system with loyalists,

And — unbelievably — it would weaken child labor protections.

Sisters and brothers, this is not reform.

It’s revenge on working people.

And yet, too many union members still vote against their own interests.

Why? Because propaganda works.

Because we are being lied to — by the media, by politicians, by billionaires who want to divide us.

That means our unions must do more than just bargain wages.

We must educate. Engage. Empower.

Because the fight ahead isn’t just about contracts

It’s about truth.

We women have proven ourselves to be strong union members — and strong union leaders.

We’ve built solidarity.

We’ve organized.

We’ve made our unions more inclusive and more reflective of the real working class.

And now it’s time for our unions to stand with us.

Many of our building trades unions have stood up to Trump, and to anyone who would divide working people.

But one union — the Carpenters — has turned its back on us.

The Carpenters leadership has disbanded Sisters in the Brotherhood, the women’s caucus that so many of us fought to build.

They have withdrawn support from the Tradeswomen Build Nations Conference, the largest gathering of union tradeswomen in the world.

They’ve withdrawn support for women’s, Black, Latino, and LGBTQ caucuses claiming they’re “complying” with Trump’s executive orders.

That’s not compliance.

That’s capitulation.

But the rank and file aren’t standing for it.

Across the country, Carpenters locals are rising up,

passing resolutions to restore Sisters in the Brotherhood

and to support Tradeswomen Build Nations.

Because they know:

You don’t build solidarity by silencing your own. And our movement — this movement — is built on inclusion, not fear.

While the Carpenters’ leadership retreats, others are stepping up.

The Painters sent their largest-ever delegation — nearly 400 women —to Tradeswomen Build Nations this year.

The Sheet Metal Workers are fighting the deportation of apprentice Kilmar Abrego Garcia.

The Electricians union is launching new caucuses, organizing immigrant defense committees, and they are saying loud and clear:

Every worker means every worker.

Over a century ago, the IWW — the Wobblies — said it best:

“An injury to one is an injury to all.”

That’s the spirit of the labor movement we believe in —and the one we will keep alive.

Our unions are some of the only institutions left with real power to stand up to the fascist agenda of Trump and his allies.

We have to use that power — boldly, collectively, fearlessly.

Because this fight is about more than paychecks.

It’s about democracy.

It’s about equality.

It’s about whether working people — all working people — will have a voice in this country.

Sisters and brothers, we’ve built this movement with our hands,

our sweat,

and our solidarity.

Now — it’s time to defend it. Together.

Solidarity forever!

Segregated Troops Encounter Racism, Show Courage

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 57

It’s easy to picture the American forces in WWII as all white. Wartime photographs, newsreels, and official histories rarely show otherwise. Flo’s own scrapbook from two years overseas with the American Red Cross and the Third Division contains no mention or images of Black soldiers.

Yet more than one million Black men and women served in the U.S. armed forces during the war. Their service was essential, though often invisible. Flo herself was no stranger to racial injustice—before the war she had been active in the YWCA’s anti-racism campaigns and in efforts to integrate the organization.

Historian Matthew F. Delmont, in Half American, argues that the United States could not have won the war without the contributions of Black troops. At the outset, however, the military tried to exclude them entirely. The Army, dominated by white supremacist segregationists, turned away Black volunteers after Pearl Harbor. Officials feared the political consequences of arming Black men. But as the war expanded, the need for manpower forced a compromise: a segregated military.

Many training camps were located in the South, where local white residents often harassed or assaulted Black soldiers. Abroad, Black Americans saw stark parallels between Nazi ideology and U.S. racial laws. The Pittsburgh Courier, a Black newspaper read nationwide, launched the “Double Victory” campaign—calling for victory over fascism overseas and victory over racism at home.

Segregated combat units fought bravely despite facing discrimination from their own commanders. The 92nd Infantry Division served in Italy beginning August 1944, possibly crossing paths with the Third Division. The Montford Point Marines, the 761st “Black Panther” Tank Battalion, and the celebrated Tuskegee Airmen also saw combat. Black soldiers fought and died at Normandy, Iwo Jima, and the Battle of the Bulge.

Most, however, served in unheralded but vital support roles. They built roads, hauled supplies, cooked, repaired equipment, and maintained the machinery of war. Seventy percent of all soldiers in U.S. supply units were Black. “WWII,” one historian wrote, “was a battle of supply,” and these troops kept that battle moving. There was even an all-Black American Red Cross contingent that ran segregated service clubs for Black troops.

The U.S. military and press often hid these contributions. Photographers were instructed to avoid showing Black soldiers in official images. When the war ended, Black veterans returning to the South were targeted for violence—beaten, harassed, and in some cases murdered—for wearing their uniforms. This had happened after WWI, and it happened again. Many veterans, like decorated soldier Medgar Evers, became leaders in the postwar civil rights struggle.

Alongside Black troops, the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team of Japanese American soldiers fought in the European Theater. Formed in 1943, the 442nd was made up largely of Nisei—second-generation Japanese Americans—many of whom had families incarcerated in U.S. internment camps. Beginning in 1944, they served in Italy, southern France, and Germany, becoming one of the most decorated units in U.S. military history.

The contributions of these segregated units—Black and Japanese American alike—were essential to Allied victory. Yet their service has been downplayed or erased from the dominant WWII narrative. Restoring these stories helps reveal a fuller, truer picture of the war that Flo witnessed.

Ch. 58: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/09/27/taking-a-break-in-nancy/

The 6888th Battalion cleaned up the mail mess

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 43

In October 1944, after her fiancé Gene was killed, Flo had trouble reaching her mother. The wartime mail system was broken.

This wasn’t just a personal problem—it was widespread. Soldiers on the battlefield were not receiving letters and packages from home. Mail, the lifeline of morale, was piling up undelivered. The men risking their lives for democracy weren’t hearing from their families, and the silence was taking a serious toll.

Flo had noticed the problem early. In letters and diary entries beginning in May 1944, shortly after arriving in Italy, she often mentioned that no mail had come. She didn’t complain—Flo wasn’t a complainer—but she noted it again and again. Others were more vocal. Across the war front, soldiers and Red Cross workers alike were frustrated and bitter. What began as a logistical issue had grown into a morale crisis.

The Army didn’t officially acknowledge the scale of the problem until 1945—by then, millions of letters and packages were sitting in European warehouses, unopened and unsorted.

Then came the 6888th.

The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion—known as the “Six Triple Eight”—was a groundbreaking, all-Black, multi-ethnic unit of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), led by Major Charity Adams. It was the only Black WAC unit to serve overseas during the war.

Their mission: clear the massive backlog of undelivered mail under grueling conditions and extreme time pressure. They worked in unheated warehouses, with rats nesting among the mailbags, and under constant scrutiny from a military establishment rife with racism and sexism. But they got the job done—sorting and forwarding millions of pieces of mail in record time.

Their work restored something vital: connection. And morale.

The 6888th wouldn’t have existed without the efforts of civil rights leaders. In 1944, Mary McLeod Bethune lobbied First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to support the deployment of Black women in meaningful overseas roles. Black newspapers across the country demanded that these women be given real responsibility and not sidelined. Eventually, the Army relented.

The women of the 6888th made their mark. Many would later say they were treated with more dignity by Europeans than they had ever experienced in the United States.

If you haven’t seen the Netflix movie The Six Triple Eight, it’s well worth your time.

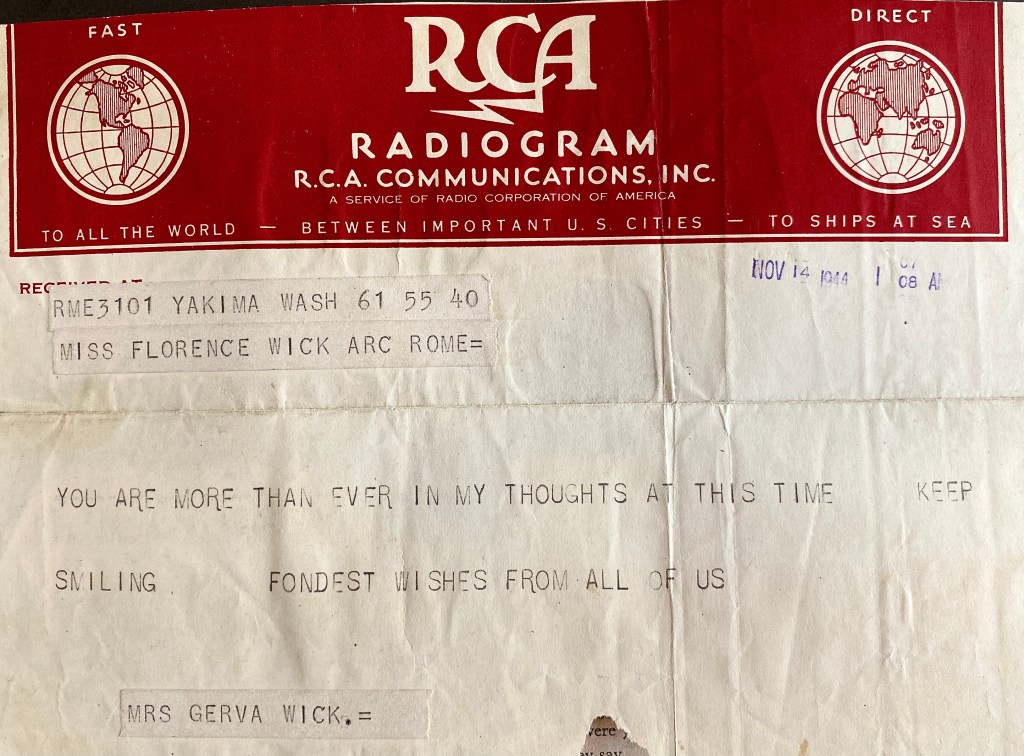

Back in October 1944, the broken mail system meant heartbreak and silence for Flo. How long did it take for her disconsolate letter to reach her mother? Gerda telegrammed back on November 14—more than two weeks after Gene had died.

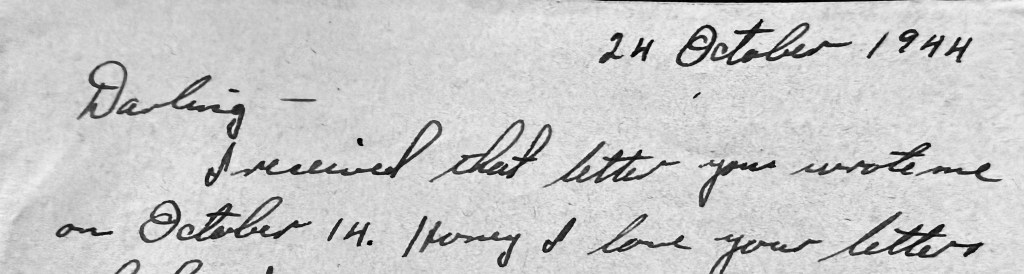

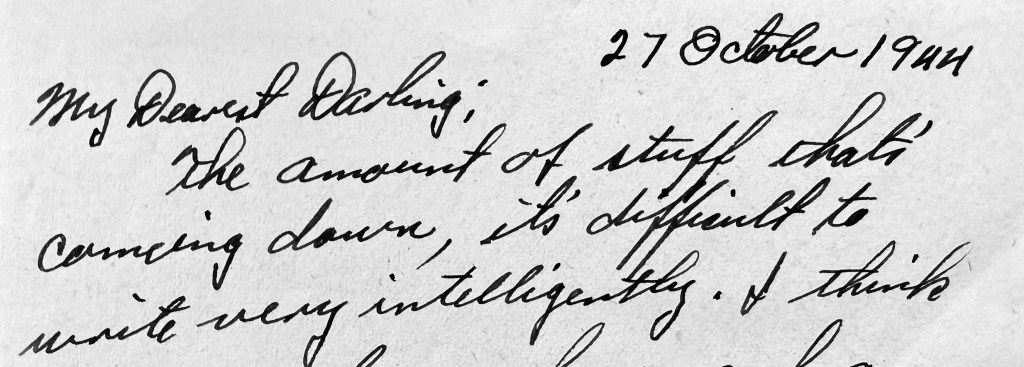

When did Flo receive Gene’s final letters? She saved the ones he wrote on October 24 and 27, but it seems likely she didn’t get them until after he was gone. He died on October 28, killed by a mortar shell. That same day, Flo wrote in her diary, “Mail from home today.” She didn’t mention anything from Gene.

In his last letters, Gene wrote about his army buddies. He worried about his little sister wanting to marry. He dreamed of peace, and of a life with Flo in the Northwest:

“Back there where the country is rugged and beautiful. Where you can breathe fresh, free air; and fish and hunt to your heart’s content. You know honey, a place where we don’t have to sleep in the mud and cold, and where the shrapnel doesn’t buzz around your ears playing the Purple Heart Blues.”

Even in the chaos of war, he tried to stay lighthearted:

“I’m writing on my knees with a candle supplying the light. I hope you are able to read it. My spelling isn’t improving very much; but with the aid of a dictionary I may improve or at least make my writing legible.”

He hoped Flo had managed a trip to Paris, and that she’d seen her sister and brother-in-law stationed there. He looked forward to getting married:

“Honey I haven’t heard from home on the ring situation yet, but I expect to before long. When I do, I shall let you know right away. I’m hoping we can make it so by xmas, if not before.”

But his letters also reflected the danger he was in:

“It’s very difficult to write a letter on one’s knees, as you probably already know. Ducking shrapnel and trying to write just don’t mix. I do manage to wash and brush my teeth most every day.”

“It’s too ‘hot’ for you to be here. I’ve got some real stories to tell you when I see you next—if I’m not too exhausted. You don’t know how close you’ve been to—I hadn’t better tell you.”

Gene’s voice comes through with vivid clarity, even across 80 years and a broken mail system.

That words eventually reached soldiers in the field and their families back home is thanks, in part, to the quiet heroism of the 6888th—who made sure love letters, grief, and hope could still find their way through a war.

Ch. 44: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/08/02/born-in-oregon-buried-in-france/

Citizens object to deportation flights

April 26, 2025

Hundreds of angry Sonoma County citizens line the road to Charles Schulz airport in Santa Rosa CA to protest Avelo Airlines contracting with ICE to conduct deportation flights. The airline is also ripping off customers by cancelling our flights and refusing to refund our money. They stole $518 from us.

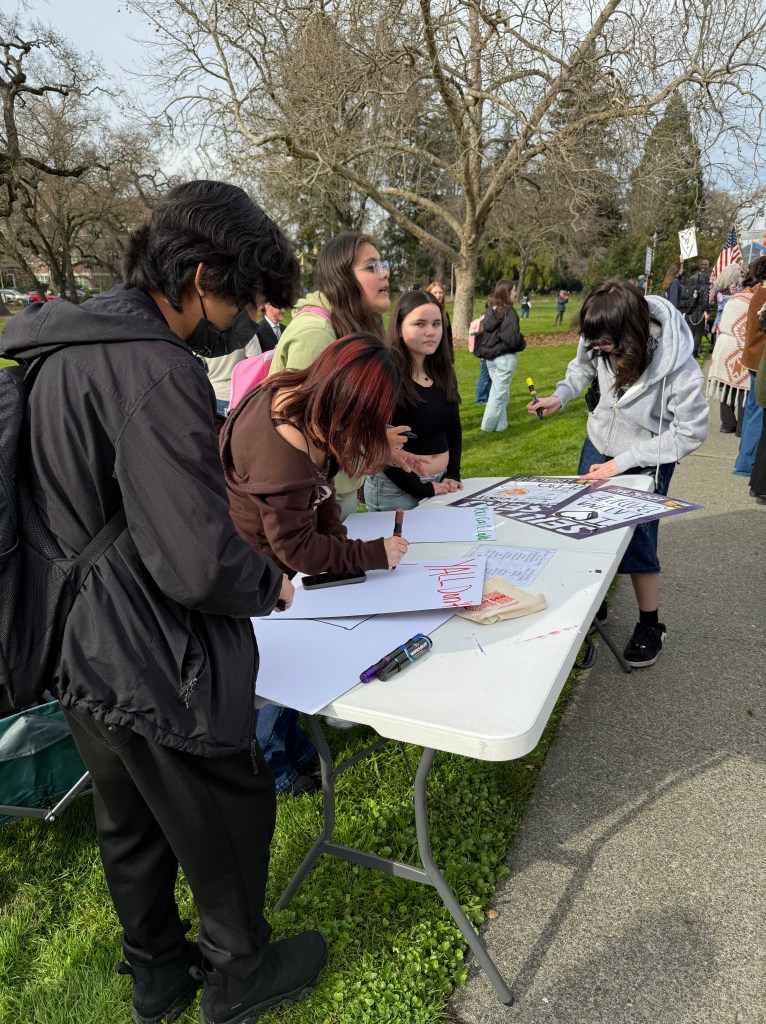

Neighbors Getting Ready for the Big Demonstration Saturday