The Rise of Antifascist Art During WWII

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 63

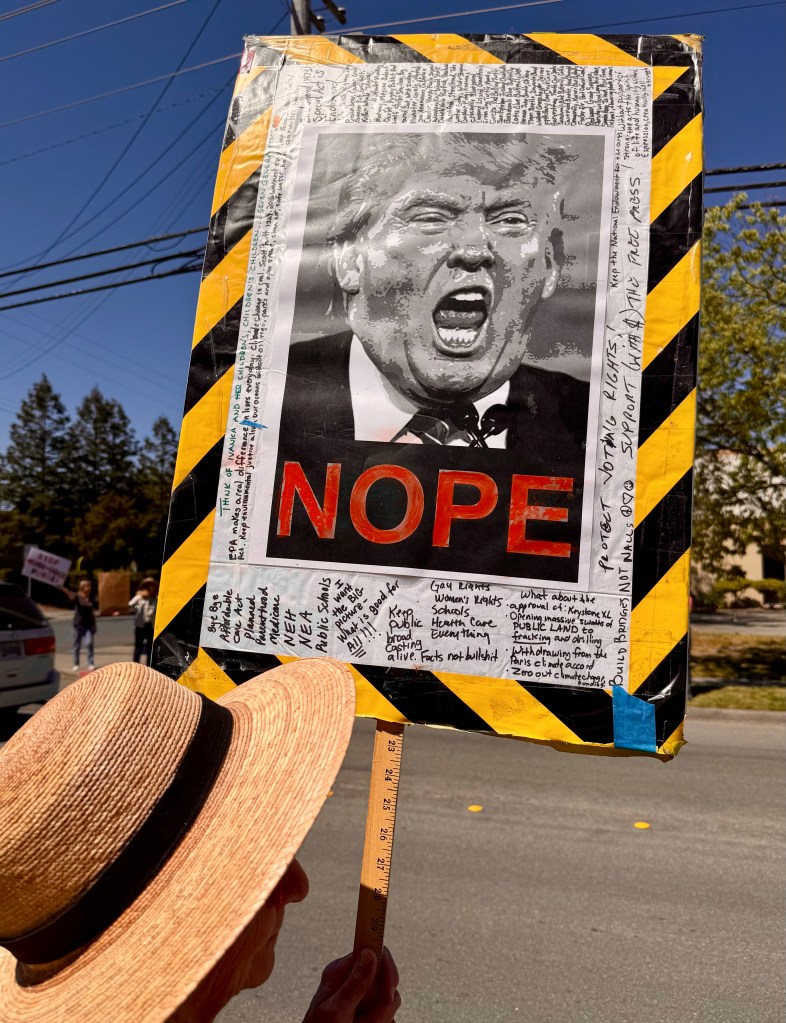

When Donald Trump illegally designated Antifa as a domestic terrorist organization, my concern for the future of our democracy deepened.

Antifa is not an organization, just a loose movement with no leaders. Because Antifa lacks structure, Trump’s move could target anyone the government assumes to be part of the movement, which could be you or me. I declare I am an antifascist. I object to the fascist takeover of my country.

Whatever you think of antifascists, probably you don’t think of the US government. But there was a time when the villains of US foreign policy were fascists. It was after the Spanish Civil War, 1936-39, in which the US refused to intervene, letting the fascists win with the help of Hitler, Mussolini and US oilmen (see Spain in Our Hearts by Adam Hochschild). It was before the CIA incorporated Nazi war criminals into its organization and focused our wrath on communists and the Soviet Union after WWII (see The Devil’s Chessboard by David Talbot).

In the aftermath of WWI, European writers sought to alert the world about the fascist threat and Americans—if they were paying attention—knew about what was happening in Europe. My mother, Florence Wick, was paying attention. What cultural influences caused her to join the American Red Cross (ARC) and serve in Europe during the second world war? What can we learn today from antifascist art?

Watch on the Rhine

In the years before television, theater played an influential role in shaping the culture. Visiting New York City in 1941, my mother saw Watch on the Rhine, an antifascist play written by Lillian Hellman. The popular play won the New York Drama Critics prize that year and was still on Broadway when Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941. Made into a movie starring Bette Davis in 1943, Watch on the Rhine was representative of a genre of antifascist art popular in the US during the early years of WWII whose purpose was to persuade isolationist Americans to get involved in the European war. It certainly influenced my mother’s decision to join the Red Cross and go to war. I think it may have been one reason she chose to join the ARC, which promised a job overseas, rather than other slots that opened for women, which may have kept her behind a desk back in the States.

I watched the movie and several others with similar messages. Some are just naked propaganda with unbelievable characters and dialog. Others, like Hellman’s, seek to educate Americans about the crisis in Europe, about class and about anti-Semitism. Hellman, who had briefly joined the Communist Party, wrote the play in 1940 following the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact of 1939. Her call for a united international alliance against Hitler contradicted the party’s position at the time. She was labeled a “premature antifascist” by the Communist Party, ironically later a moniker used by the FBI during the McCarthy purges to target communists. Her lover, Dashiell Hammett, who had also joined the Communist Party, wrote the screenplay.

His introduction reads: In the first week of April 1940 there were few men in the world who could have believed that, in less than three months, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Holland and France would fall to the German invaders. But there were some men, ordinary men, not prophets, who knew this mighty tragedy was on the way. They had fought it from the beginning, and they understood it. We are most deeply in their debt. This is the story of one of these men.

The man is Kurt Muller, a German who has devoted his life to the antifascist movement. We learn that he and many of his comrades fought in international brigades along with the Spanish Republicans to defend Spain’s democratically elected government against Francisco Franco’s fascists. They and others have constructed an underground antifascist organization in Europe. Watch on the Rhine shows us that fascists come in many shades; that Americans, naive about world politics, haven’t moved so far from slavery; that Bette Davis (bless her heart) excelled at overacting. The part played by Davis, Muller’s American wife, was expanded for the movie to make use of her star power at the box office.

The play is set in the Washington DC mansion of the wife’s family, whose dead patriarch had been a respected US Supreme Court justice. The family matriarch, Mama Fanny, runs it like a plantation, overseeing Black servants with strict control. When Joseph, the male servant, is summoned, he answers “Yasum.”

But Joseph gets some good lines. When Mama Fanny orders, “That silver has lasted 200 years. Now clean that silver,” Joseph says, “Not the way you take care of it Miss Fanny. I see you at the table and I say to myself, ‘There’s Miss Fanny doing it to that knife again.’ “

Hellman uses the three Muller children, sophisticated, language rich and worldly, to teach Americans about the outside world. “Grandma has not seen much of the world,” says the oldest, Joshua. “She does not understand that a great many work most hard to get something to eat.”

We learn that the antifascist movement is nonviolent. The youngest kid, Bodo, says, “We must not be angry. Anger is protest and should only be used for the good of one’s fellow man.”

The movie is both a critique of American culture and an attempt to school Americans about developments in Europe. Hellman did deep research for her script, and I thank her for helping me to understand this historical period and the forces that shaped it. Like most films from this era, it’s not available on Netflix, but I was able to check it out from the San Francisco Public Library.

The Moon Is Down

During Hitler’s rise, Nazis were winning the propaganda war. Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 Nazi propaganda film, Triumph of the Will, was and still is much admired. Alarmed artists approached the US government with proposals for antifascist plays, movies and books, among them the famous writer John Steinbeck. The result of his effort, the novella, The Moon is Down, was published in March 1942. The next month it played on Broadway and a year later premiered as a movie. Its purpose was to motivate the resistance movements in occupied countries. The sinister title comes from Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

I accidentally discovered the thin book in a friend’s library and read it with great interest. It describes life in a town that has been invaded and occupied by the German fascist army.

There is bloodshed. Orders are followed. People resist, are arrested and executed. People flee. Some people collaborate. Others form an underground to communicate with those on the outside. At the end of the book, the war is still going. But the invaders have been surrounded and we are very aware that the invaders have become the harassed. In a way, the occupiers have become the occupied.

Steinbeck acknowledges the humanity of the enemy. We learn as much about the motivations and humanness of the invaders as the invaded. For that reason the book was criticized mercilessly in the US and Steinbeck’s patriotism questioned. But Europeans loved it. It was translated into many languages and became the most popular piece of Allied propaganda in WWII.

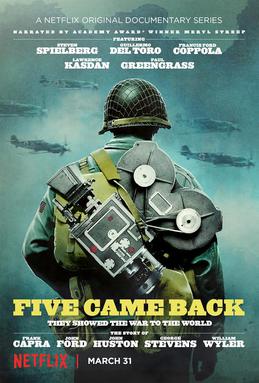

Five Came Back

Things weren’t looking good for the Allies as the US joined the war effort after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Germany and Japan were conquering Europe and the Pacific. The US had only just started to gear up its factories to make war materiel and Europe feared we wouldn’t get it there in time to stop the Nazi advance. It was during this time that the US antifascist propaganda machine went into high gear.

From 1942 to 1945, Frank Capra directed a series of seven antifascist propaganda films, narrated by the actor Walter Huston. The series, called Why We Fight, was produced by the War Department to make the case for US involvement in WWII. These films can now be accessed online. I also saw Five Came Back, a three-part Netflix series about five American film directors, including Capra, who produced propaganda for the US government during the war. The others were John Ford, William Wyler, John Huston, and George Stevens.

Making movies of the war changed the filmmakers as well as audiences. We learn that they were haunted by what they saw. Wyler was shocked by racism against Black soldiers and refused to make a film meant to recruit Blacks. Stevens, at Dachau, realized he should be there to film evidence of crimes against humanity, not propaganda. Ford turned to drink after witnessing the bloodbath on D-Day. Huston took on PTSD only to have his film suppressed by the government. Racism was present in these films. While Germans were depicted as humans, Japanese were often seen as subhuman caricatures. The government worried, rightly, that violence against Japanese Americans would result. Then, in 1942, it incarcerated them until the end of the war.

Women in WWII: 13 short films featuring America’s Secret Weapon

Most of these are US military propaganda films whose purpose was to convince women to join the WACS or other service, and also to persuade men that women could do the work. Some were written by Eleanor Roosevelt and narrated by famous actors like Katherine Hepburn. The American Red Cross, in which my mother served, wasn’t mentioned, but there was a picture of an ARC club in North Africa.

I wish the government had made films like this for women in the trades. In one scene a couple of men are talking on their front porch about how one’s sister wants to join the WACS and they think she’s crazy. It’s a man’s war, they say. Then the film counters their sexism and shows competent women doing all sorts of jobs. However, these films also endeavored to persuade women that they were taking men’s jobs and they needed to go back home after the war and relinquish their war jobs to returning soldiers. It was made clear that the jobs belonged to men.

I don’t know if my mother saw any of these films, but it was this sort of government propaganda that propelled her and her generation into World War II. When the enemy was fascism, she was “as patriotic as they come,” according to her sister. Only after the war did she begin to question the government-constructed enemies of the state.

Imaginary Witness: Hollywood and the Holocaust

Released in 2004, this film makes the case that the story of the Holocaust has been told to the world by films made in Hollywood, starting with Warner Bros. Confessions of a Nazi Spy in 1939, then MGM’s The Mortal Storm in 1940. Neither of these films used the word Jew. The Jewish studio heads wanted to stay in the closet and just be known as Americans. Also, the movie industry made a lot of money from selling its films to Germany during the early years of Hitler’s takeover. Some historians now view studio directors as Nazi collaborators.

Finally in 1940 Charlie Chaplin used the word Jew in The Great Dictator, which he made with his own money. Imagining that an antifascist film can also be hysterically funny might be difficult until you see The Great Dictator. Chaplin slays as Adenoid Hynkel, a thinly disguised Hitler. Jack Oakie’s spoof of Mussolini inspires hilarity. This film is testament to Chaplin’s comic genius. In the globe scene, Chaplin/Hynkel performs a ballet dance with a balloon earth, achieving perfect domination. Chaplin impersonates Hitler to great comic effect. He watched Riefenstahl’s propaganda film Triumph of the Will to learn Hitler’s speech patterns and body movements. Chaplin later said that if he had known the extent of Nazi atrocities, he wouldn’t have made the film. I’m so glad he did.

My mother told us kids stories about her time in Europe during the war, but she never talked about the Holocaust and we were not taught about this historical period in school. So I didn’t learn until 1970 that she had been present at the liberation of Dachau. What finally got her talking was an American TV mini-series, QB VII, about a British court case involving concentration camp crimes. It exemplifies how American media jogged the memories and imaginations of war survivors even 25 years after the war.

Night Will Fall

In 1945 a team of British filmmakers overseen by Alfred Hitchcock went to Germany to document the Nazi death camps. Their documentary, German Concentration Camps Factual Survey, was suppressed and then lost for seven decades. Night Will Fall, a 2014 documentary directed by Andre Singer, chronicles the making of the 1945 film and includes original footage. These images are hard to watch, but I think we need to see them, to witness the consequences of fascism.

The death camp films were suppressed partly because they were thought too graphic for British and American tastes. And American tastes had changed almost as fast as superstate enemies revolved in Orwell’s dystopian novel, 1984. The Germans, our most recent deadly enemy, had become our friends. The Soviet Union, our recent ally, and communism, was now our mortal enemy.

Ch. 64: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/10/21/a-visit-from-marlene-dietrich/