Address to the University of Washington Labor Archives gathering May 12, 2018

Tradeswomen sisters, friends and advocates! Today we celebrate the victory of our movement to integrate the construction trades. Women have achieved parity. Sexual harassment and sex discrimination are things of the past.

Just kidding.

The truth is that after nearly a half century of organizing, our movement has failed to achieve parity or even a critical mass of women in the construction trades. But we have made some amazing gains. I want to talk about that and I want to pose a question to you all.

Let me give a little background and then we’ll hear from the distinguished activists on our panel and in the audience. Thanks to Conor Casey and the UW Labor Archives we have a panel of veteran tradeswomen foremothers. These crones are woke!

Here’s my backstory. I grew up in Yakima, went to college at Washington State University in Pullman and then moved to Seattle (the big city) in 1974.

I know many of you are as old as I am and were here in the 1970s. For those who were not, let me try to paint a picture of the times. Does anyone remember the admonition “Will the last person to leave Seattle turn out the lights?” That was in 1971. Remember the recession? Boing, the main employer in town, had laid off thousands of workers and the city was in a funk.

I was a young person in my 20s just trying to survive. With a degree in journalism, I worked as a temporary office worker, as a parking lot attendant, as a community organizer in the VISTA program, as a reporter at The Facts newspaper, all the while looking for a job or a better job. When I couldn’t get hired as a cocktail waitress, I was offered a “job” as a topless dancer working for tips.

We lived collectively, partly to save money but also because we believed in collective living. Those big mansions on Capitol Hill made great collective houses. We struggled to pay for groceries and heat. But at least rent was much less expensive than it is now.

Tradeswoman historian Vivian Price wrote about this period: “Seattle was a magnet city in the 1960’s and 1970’s, attracting people who were interested in social change to move there…Seattle was on the cutting edge of social movements. It was a city known for being a center for the women’s movement, with a thriving lesbian and gay culture, a strong old and New Left, and a vibrant movement among communities of color. Activists from each of these movements crossed paths and in some cases supported one another’s efforts. In some cases, support became collaboration, to each other’s mutual advantages.”

The city was a cauldron of dissent. Left and communist organizations flourished. The Vietnam War continued. Angry discontented citizens demonstrated in the streets. Many people felt the only solution to our foreign policy crisis was to overthrow the state. Bombings were frequent.

At the same time community activists sought to build new institutions in sectors that were not serving us—women’s and poor people’s health care, medicine, the food industry, banking, transportation, living arrangements, marriage, work. The University YWCA became a focal point of women’s organizing.

The 1963 Equal Pay Act and the 1964 Civil Rights Act gave us new employment rights, but they had not yet extended to the construction trades. We formed an organization, Seattle Women in Trades. We were just rabble—unemployed women who wanted good paying jobs. From the beginning we had two powerful adversaries—the contractors and the unions.

Our struggle was for affirmative action. We demanded access to jobs that had been denied to us. We saw ourselves as part of the feminist movement and also the civil rights movement.

In Seattle we collaborated with several other organizations:

- Mechanica, founded in 1973 and connected with the YWCA, sought to help women find jobs in nontraditional fields

- United Construction Workers Association, a group of black people led by Tyree Scott and Bev Sims who had been agitating for entry to the construction trades since the 1960s

- The Alaska Cannery Workers Association, active since the 1930s, was made up of Filipino workers who traveled to Alaska to work

- The Northwest Labor and Employment Law Office, LELO, founded by United Construction Workers, Alaska Cannery Workers and the farmworkers union, in 1973

Even at that time Seattle was miles ahead of other cities in regard to affirmative action. And this is the question I pondered for decades and I hope you will help me answer: Why was Seattle so far ahead? Let me pose some possible answers.

- First, the Northwest has a history of radical dissent and union organizing that goes way back. We stood on the shoulders of those activists

- Women, laid off elsewhere after WWII, were still working in the shipyards by the 1970s. I heard about women working mucking out the tankers.

- The black freedom movement had a profound impact on women’s fight for equal employment. United Construction Workers led the way in the 1960s and early 70s with street actions.

- Black men had filed a class action lawsuit in 1969, which resulted in the Seattle plan. It became a national model for affirmative action in the construction industry.

- Radical Women, Clara Fraser and the fight to integrate Seattle City Light was crucial. I wish I had time to tell this story. Women who got in as line workers were subjected to horrific harassment. One woman, Heidi Durham, fell from a power pole and broke her back.

- Mechanica and early feminist organizing through the YWCA.

- Supporters within the city government created local goals and timetables for women in nontraditional jobs–12% in 1973.

- Finally I credit individual humans. Pat Anderson, one of the original organizers of WIT, worked closely with UCWA, ACWA and LELO. She was the glue that held our coalition together. Pat died in 2009. I don’t want her contribution to our movement to be lost to history.

I say we failed to achieve critical mass, but let’s look at some of what we accomplished on a national scale.

- Our 1976 lawsuit against the US Department of Labor (USDOL) gave us Federal regulations laying out goals and timetables for women and minorities in the construction trades.

- We pushed for and won state and local affirmative action programs.

- There had been no women, and then our numbers increased to 2.7 percent in the construction trades, about where they have remained ever since.

- We succeeded in integrating some nontraditional blue-collar jobs like bus driver, mail carrier, police and firefighter.

- We built coalitions with others in the civil rights movement.

- We organized awesome conferences and trade fairs like the 39thWashington Women in Trades fair yesterday. Our next international conference, Women Building the Nation, will be here in Seattle October 12-14, 2018.

- We collaborated with unions and the labor movement.

- We worked to get women’s issues addressed in contract negotiations.

- Through court cases, we made laws against sex harassment.

- We implemented sexual harassment training of foremen, contractors and coworkers.

- With few resources, we built organizations in many states and a national network of organizers

- We addressed unmanly issues such as PPE and on-the-job safety.

- We created publications like Tradeswomen Magazineas a way to tell our stories and interact with tradeswomen around the country and the world.

- We built a vibrant diverse international movement still active today. I would argue that we changed the world.

I was one of the founders of Seattle Women in Trades. When we first started we were just a bunch of women who wanted decent work. Why did we want jobs in construction? Money. Trades jobs paid three or four times what “women’s jobs” paid, enough to support a family. Also we wanted an escape from confining office work. We wanted an escape from pumps and pantyhose. We wanted to build something. We wanted to break down the barriers.

In the 1970s we were lucky to have CETA, a federal job-training program. In Seattle we had Seattle Opportunities Industrialization Center, which had classes in electrical wiring, plumbing, carpentry. That six-month program was my destination. But women first had to reckon with sexism. I was asked if I could type and when I replied yes (the last time I admitted that), they told me I was not eligible for the electrical training program because I already had skills that would just go to waste. Fast-talking and possibly a threat got me in and that training was the basis for my career as an electrician.

My goal was to get into the electricians union, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. But when I applied, I was rejected. They said I was too old. I was 26. That’s when I decided to move to San Francisco.

I arrived in San Francisco in the fall of 1976. There it was the same story. We founded organizations for women in blue-collar nontraditional work, but most of us were still wannabes. We still didn’t have jobs and the construction unions’ doors were still closed to us, though they were feeling pressure to integrate. I started a contracting business with a partner, and then joined Wonder Woman Electric, an all-female contracting company. Later, in 1980, I was able to join the union only because San Francisco was experiencing a construction boom and they needed skilled workers.

In 1976, with the help of several feminist law firms including Equal Rights Advocates and Employment Law Center in San Francisco, women sued the USDOL for discrimination. This lawsuit resulted in goals and timetables for women in construction trades, 6.9 percent at the beginning. Seattle was used as a model in the 1978 federal regulations. Of the eleven women who signed on to the lawsuit, three were from Seattle Women in Trades: Diane Jones, Mary Lou Sumberg and Beverly Sims. The others were from San Francisco, Washington DC, Fairbanks Alaska and Walla Walla WA.

When tradeswomen heard about the federal regulations, signed into law 40 years ago on May 8, 1978, we celebrated! We did the math and figured it would only be a few years until we achieved critical mass in the trades. We thought if we could just get to ten percent, we would be less isolated and might be able to change the male culture of the construction site. If Jimmy Carter had stayed in the White House we might have made it, but in 1980 Reagan was elected and he immediately began dismantling affirmative action programs. We still had the laws, but no enforcement.

The right wing successfully challenged our old organizing strategies. In the 90s and aughts in California and Washington anti-affirmative action ballot measures essentially made affirmative action illegal. We could no longer do targeted enforcement in these states. Affirmative action, the most important tool we had to fight employment discrimination, was effectively dead. Class action lawsuits had been an effective tactic in the 70s, but new restrictions have put an end to that.

Here’s my short answer to the question: Why was Seattle so far ahead?

- People of color (men and women) paved the way for women fighting for affirmative action.

- The first class action lawsuit filed in 1969 by LELO succeeded in creating the Seattle Plan, an early affirmative action plan.

- We formed effective coalitions with other organizations. Tradeswomen were and still are a tiny demographic and coalitions are necessary.

- Seattle’s kickass feminist activists built some of the earliest and most effective tradeswomen advocacy organizations. Some of them are here with us today.

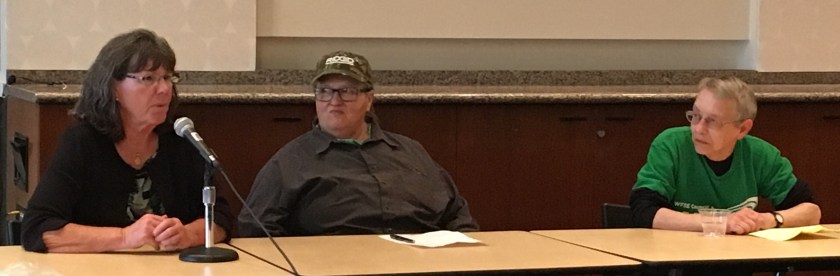

We have some distinguished activists from the Tradeswomen Movement here today, women who have spent their lives in service to our cause. I’d like to introduce Connie Ashbrook, the founder and ED (retired) of Oregon Women in Trades and Nettie Doakes of Seattle City Light. Now let’s hear from the tradeswomen panelists: Plumber Paula Lukaszek, Ironworker Randy Loomans, and Plumber Zan Scommodau.

To cap off my trip to Seattle, I visited some of my old haunts with a friend from back in the day. I was surprised to see the Comet Tavern still there on the edge of Capitol Hill. So much else has changed in Seattle. When I told the bartender I’d danced on the bar the night Nixon resigned, August 9, 1974, he said, “This beer’s on the house.”

To watch the video of this event: http://www.seattlechannel.org/videos?videoid=x91548