Third Division fights its toughest battle of the war

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 53

The fight for the Colmar Pocket rages through late January 1945, a brutal campaign largely overshadowed by the final days of the Battle of the Bulge. Audie Murphy, then a young lieutenant in the 15th Infantry Regiment, endures the worst days of his war.

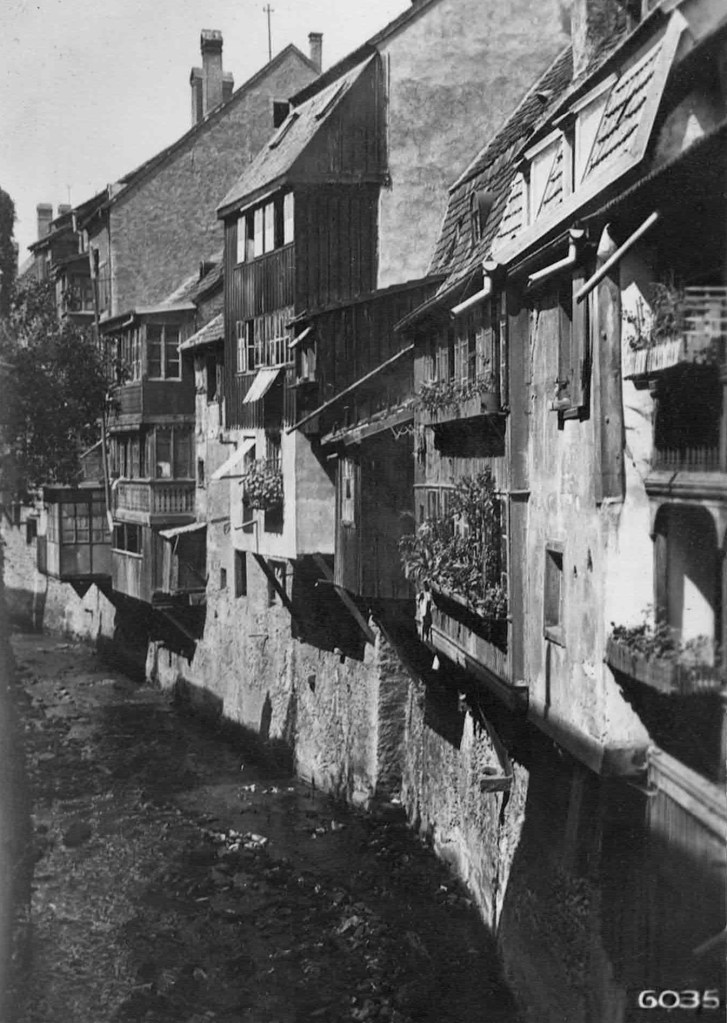

Through the freezing night he and his men take turns on watch. He nods off, his hair freezing to the ground, and wakes with a jerk when gunfire cracks, leaving patches of hair in the ice. By morning, a bridge over the Ill River is finally usable; a few tanks cross to join them—comforting, but also a sign that there will be no retreat.

They form up for another attack. The quiet woods erupt—mortars, machine guns, rifle fire. Murphy watches two lieutenants leap into the same foxhole; a shell follows them in and ends their lives instantly. He is knocked down by another blast, his legs peppered with fragments, but still able to fight. Tanks push forward, only to be hit and burst into flames. Crewmen stumble out, burning, screaming, cut down by enemy bullets as they roll in the snow.

By nightfall the company is shattered. They huddle in the cold, eating greasy rations, waiting for ammunition and replacements. Company B has lost 102 of its 120 men; every officer but Murphy is gone. With only seventeen men left in his zone, he receives orders: move to the edge of the woods facing Holtzwihr, dig in, and hold.

The ground is too frozen to dig, so they stamp along the road to stay warm, waiting for daylight—the most dangerous hour. Their promised support does not arrive. Two tank destroyers move up, but by afternoon the situation worsens. Six German tanks roll out of Holtzwihr and fan across the field, followed by waves of infantry in white snowcapes.

One tank destroyer slides uselessly into a ditch; the crew bails out. Artillery begins to fall on Murphy’s position. A tree burst wipes out a machine-gun squad. The second tank destroyer takes a direct hit; its surviving crew staggers away. Murphy realizes the line is collapsing. Of 128 men who began the drive, fewer than forty remain, and he is the last officer. He orders the men to pull back.

While directing artillery fire by telephone, he fires his carbine until he runs out of ammunition. As he turns to retreat, he sees the burning tank destroyer. Its machine gun is intact. German tanks veer left, giving the flaming vehicle a wide berth. Murphy drags the field phone up onto the wreck, hauls a dead officer’s body out of the hatch, and uses the hull for cover.

From the turret he mans the machine gun, calling artillery on the field while firing into the advancing infantry. Smoke swirls; the heat of the fire warms his frozen feet for the first time in days. He cuts down squad after squad, sowing confusion; the Germans cannot locate him and expect the burning vehicle to explode at any moment.

When the smoke lifts briefly, he spots a dozen Germans crouched in a roadside ditch only yards away. He waits for the wind to clear the haze, then traverses the barrel and drops all twelve. He orders more artillery. Shells crash around him; the enemy infantry is shredded, and the German tanks pull back toward Holtzwihr without support.

Another bombardment knocks out his telephone line. Stunned, Murphy finds his map shredded with fragments and one leg bleeding. It hardly registers. Numb and exhausted, he climbs off the tank destroyer and walks back through the woods, indifferent to whether the Germans shoot him or not.

Murphy was 19 years old. These are the actions that win him the Congressional Medal of Honor.

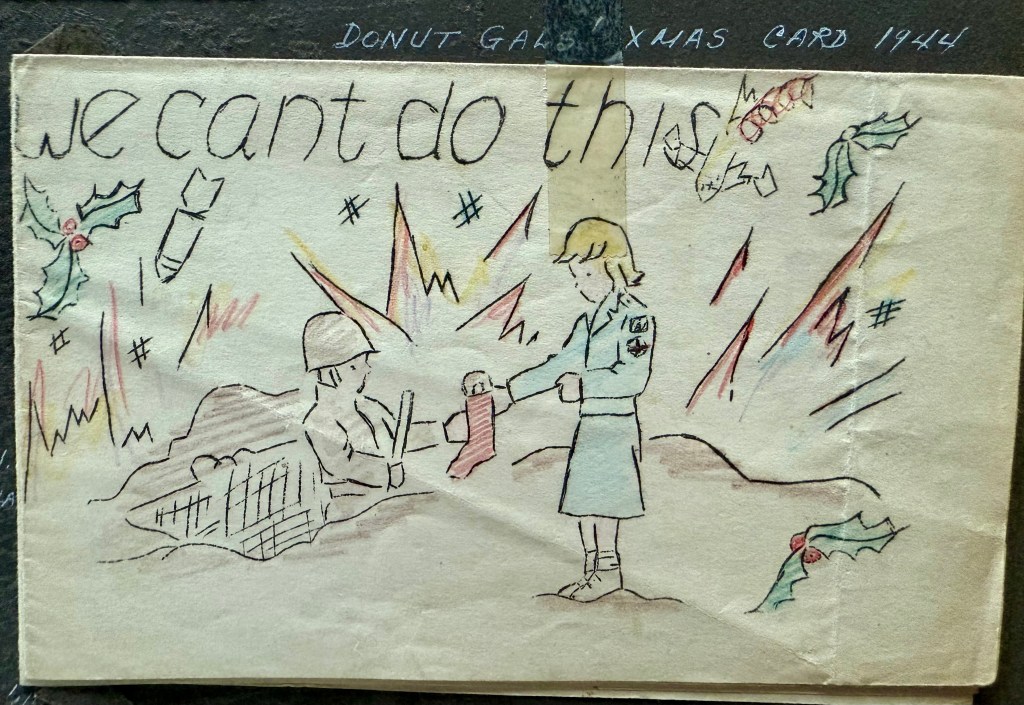

Ch. 54: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/09/11/flo-and-janet-shoot-guns/