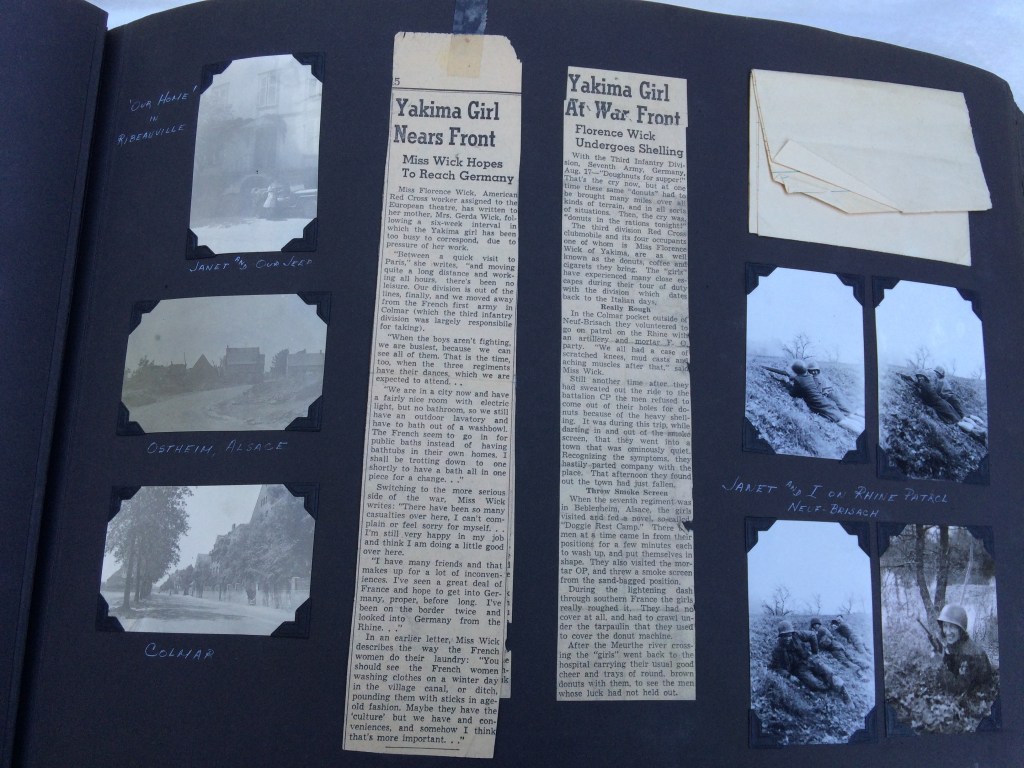

ARC Women the Only American Females to Shoot in WWII

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 54

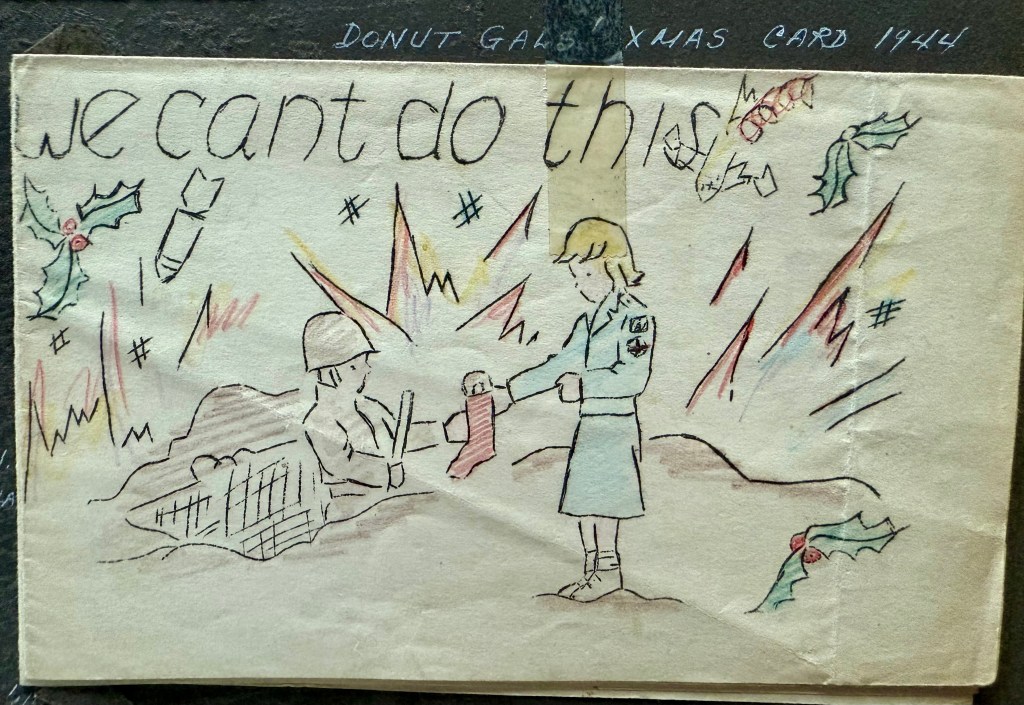

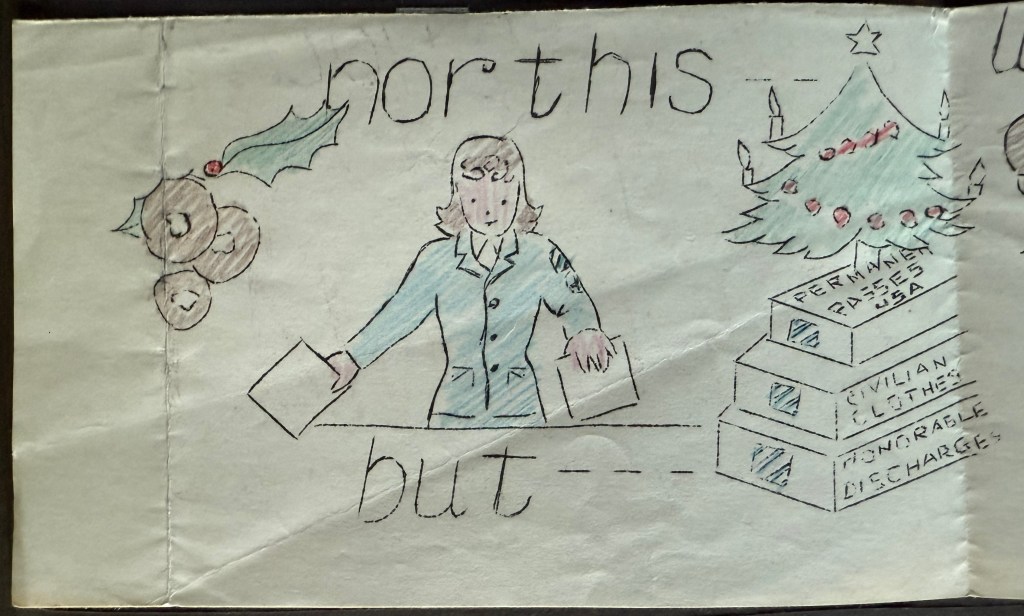

American women were strictly forbidden from shooting guns during WWII or serving in any combat position. The WACs, the Women’s Army Corps, were disparaged because Americans thought they would be too close to war and women should be protected from war. The ARC women flew under the radar because they were referred to as volunteers (even though it was a paying job), and as “girls” and because they primarily worked as nurses. Their carefully crafted image was as noncombatant helpers of soldiers, humanitarian aid workers, not fighters.

the American Red Cross worked hard to establish these women as safe and non-threatening to the social norms of the time. In so doing, it allowed them to gain access to battle and combat to an extent no American women had before.

The Allies and Germany had lost such extensive manpower during the First World War that women were allowed much more active military roles in the Second World War. Unlike American women, Soviet women were fighters on the front lines of the war.

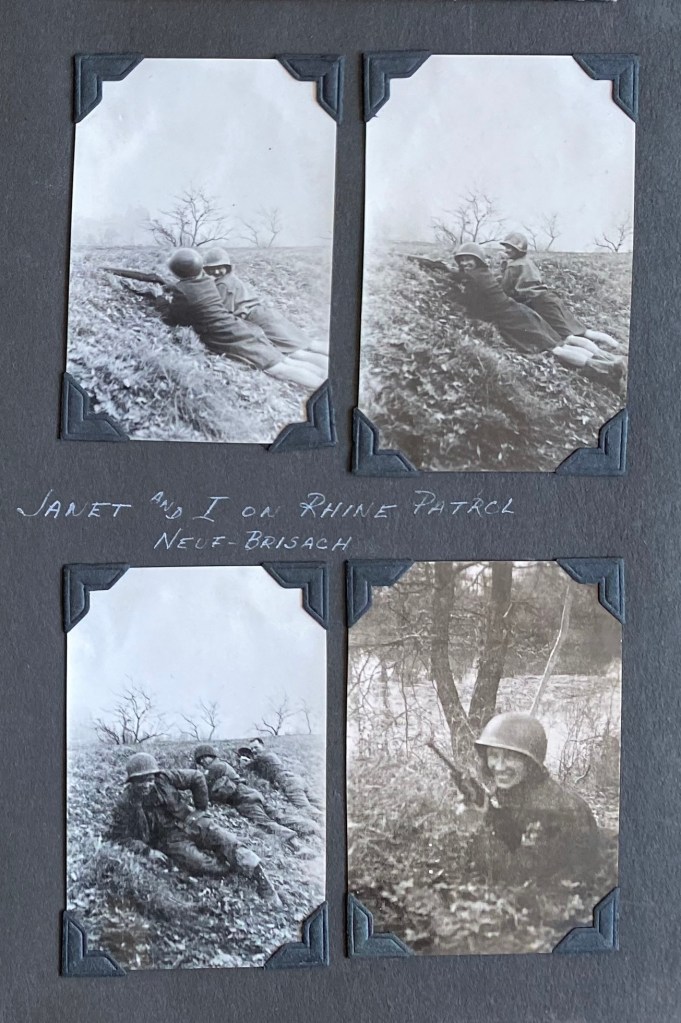

As it turned out, the ARC clubmobilers may have been the only American women in the war who actually shot guns. They were closer to the front lines of the war than any other women.

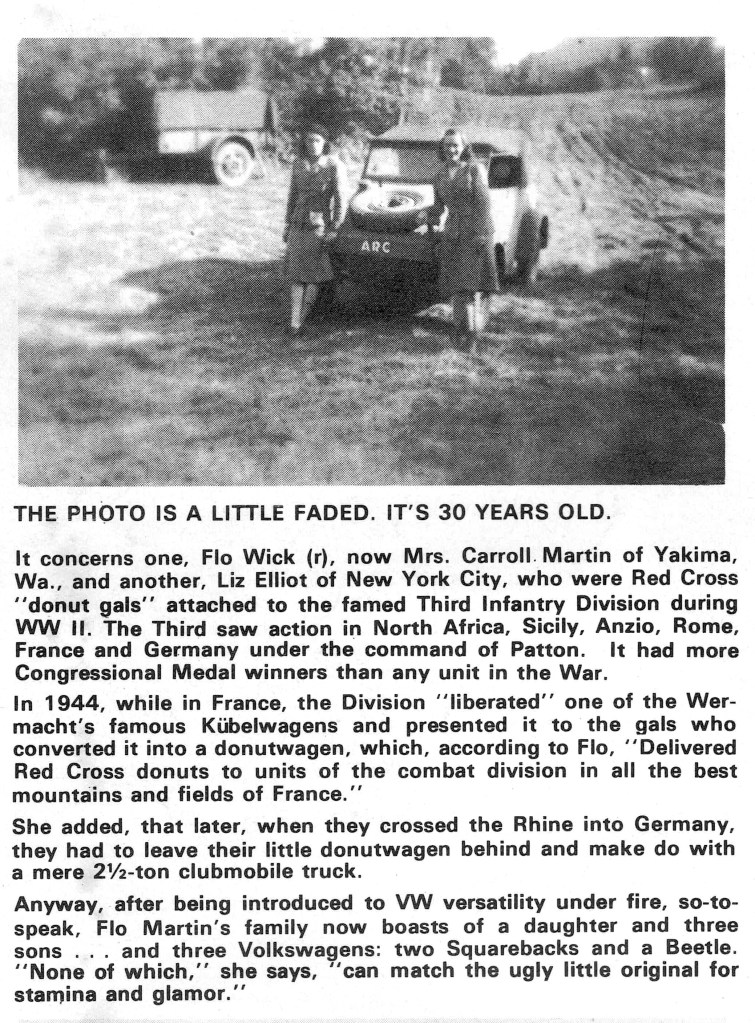

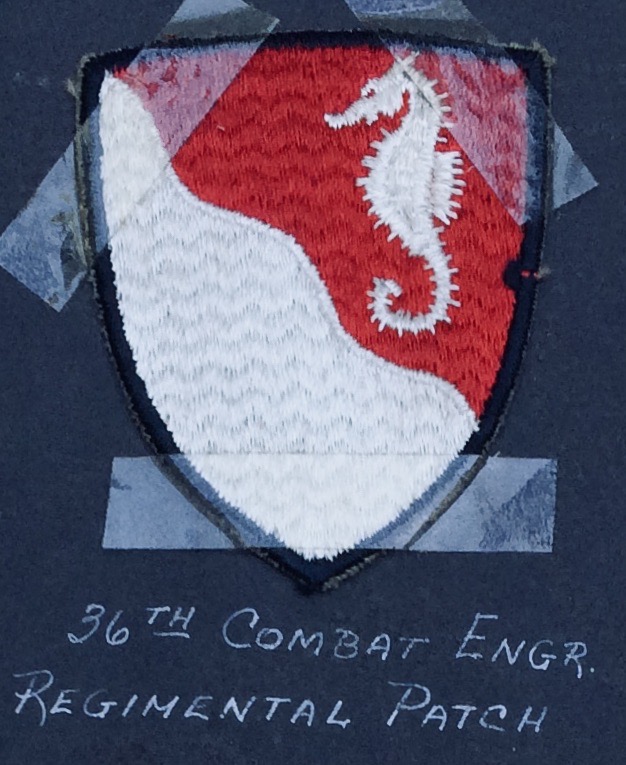

They also experienced many close escapes during their tour of duty with the Third Division.

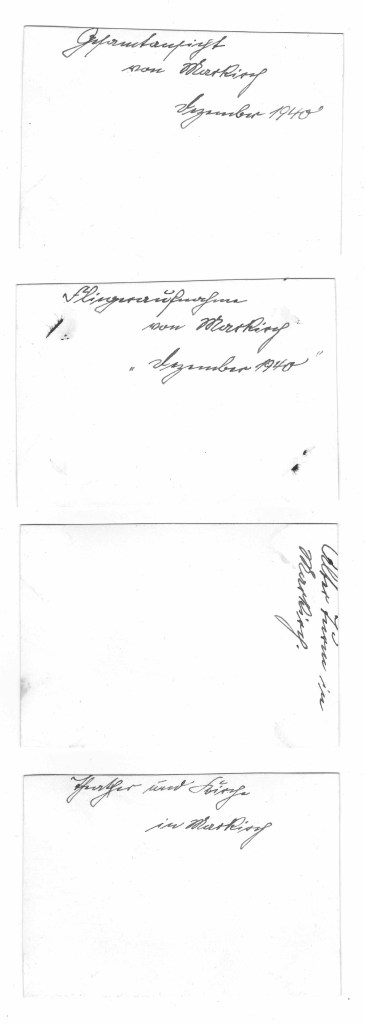

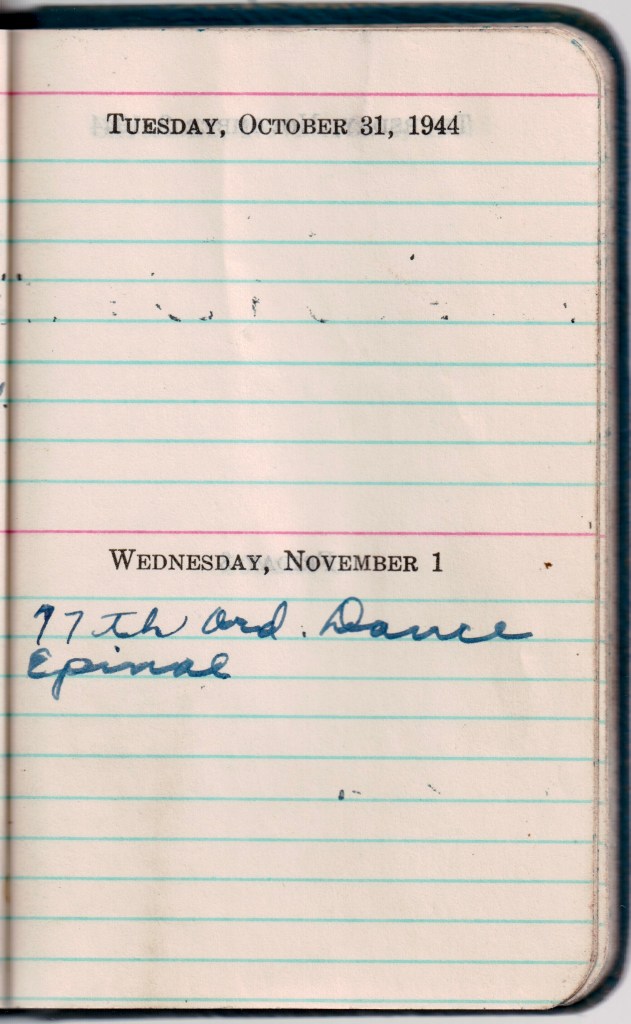

Flo and her comrades got the chance to shoot in the freezing winter of 1944-45, during some of the hardest fighting of the war. In the Colmar Pocket outside of Neuf-Brisach they volunteered to go on patrol on the Rhine with an artillery and mortar FO (field operations) party. They also visited the mortar OP (observation post) and threw a smoke screen from the sand-bagged position.

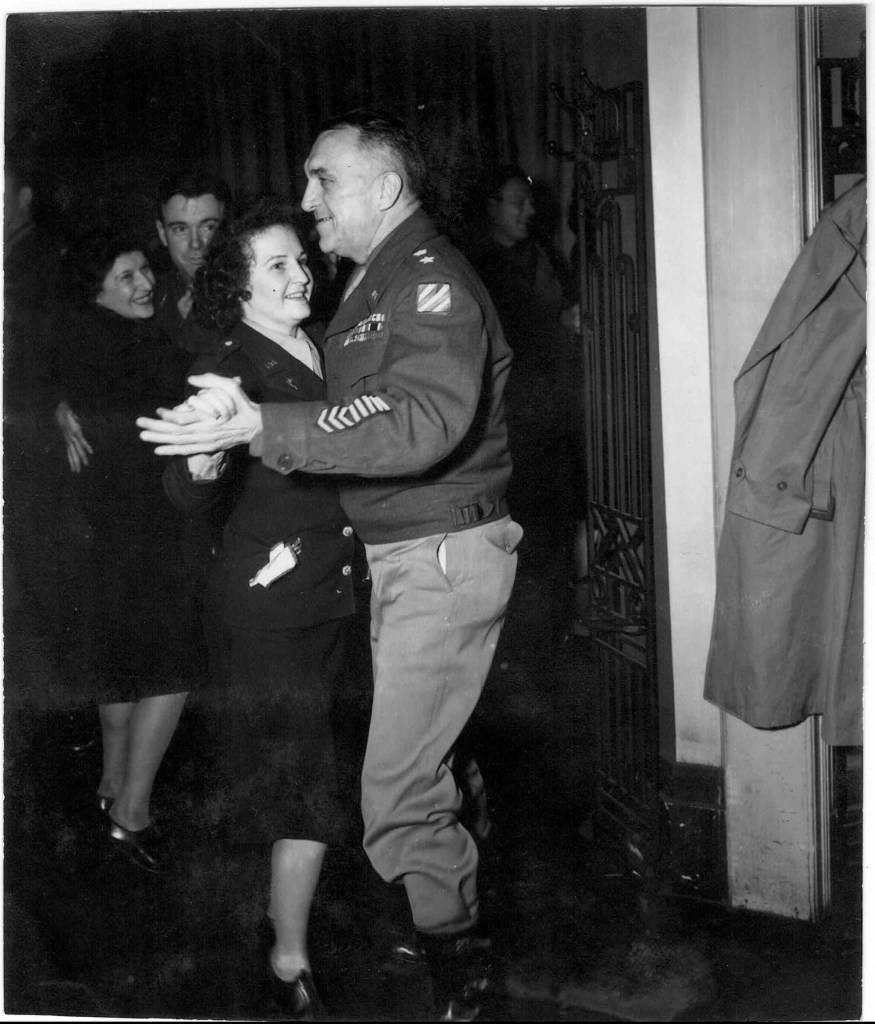

Because the clubmobilers saw the soldiers and worked with them daily, the women were seen as part of the team. The men wanted to show them what it was like on the front line and the women wanted to be part of the action. Their comrades showed the women how to shoot.

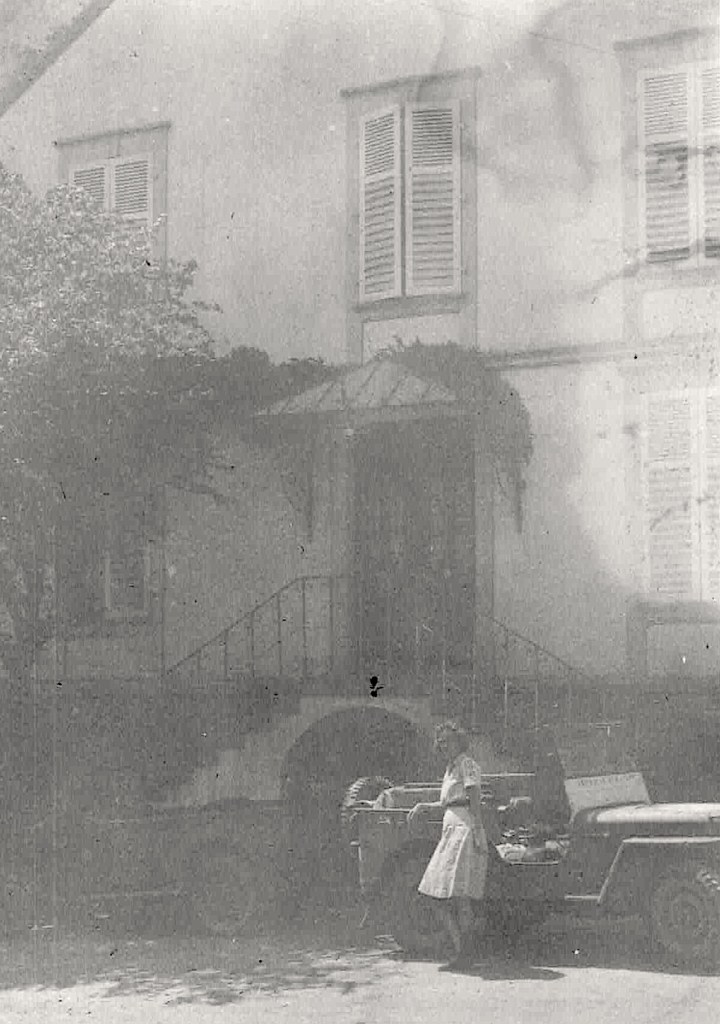

Photos of her from that day show she was wearing the ARC regulation uniform—a skirt—while lying in a trench aiming a rifle.

I don’t know whether Flo had ever shot a gun, but she was part of a hunting and fishing culture in the Northwest, so she may have. I have a picture of her posing with a deer carcass and holding a rifle taken after the war.

Flo was quoted in a newspaper article: “We all had a case of scratched knees, mud casts, and aching muscles after that.”

Still another time after they had sweated out the ride to the battalion CP (command post) the men refused to come out of their holes for donuts because of the heavy shelling.

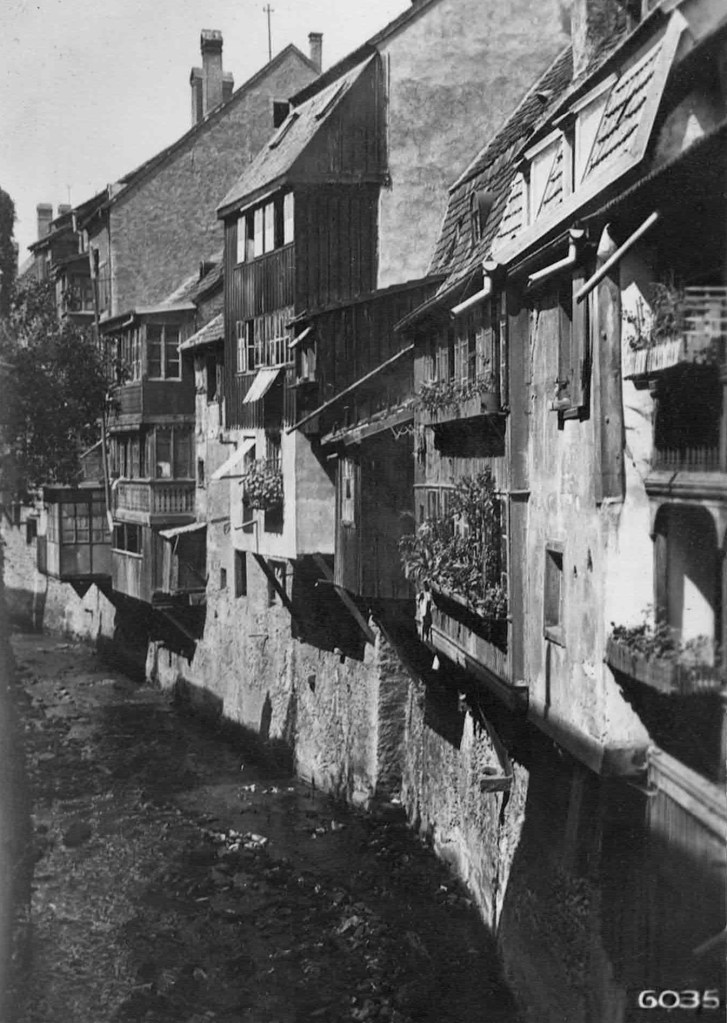

It was during this trip while darting in and out of the smoke screen, that they went into a town that was ominously quiet. Recognizing the symptoms, they hastily left the place. That afternoon they found out the town had just fallen. It had been occupied by the Krauts during their visit.

When the Seventh Regiment was in Beblenheim, Alsace, the clubmobilers visited and fed a novel, so-called, “Doggie Rest Camp.” There two men at a time came in from their positions for a few minutes each to wash up, and put themselves in shape.

According to the newspaper report, “The quartet is not now up to combat strength as Miss “Fritzie” Haugland, Berkeley, Calif. is hospitalized, but her three running mates are doing a fine job…. They are just what their patch proclaims—part of the outfit.”

Letters from Third Division friends confirm that the clubmobilers’ exploits were dangerous and put them in the line of fire.

On Jan 31, 1945, Lt. Col.Chaney wrote: Please don’t be as reckless as you have been, and stay out of range of shell fire.

Sincerely, Chaney

On March 5, 1945, Mel wrote:

Yes, I can well imagine your time is not your own, particularly when the Div. is getting their well-earned respite from the 88’s. Your own “combat time” was hardly a surprise to me. To me, you were the type that would do such a thing, just for the hell of it! Stick to your donuts, honey, and let others do the OP shift—I’d hate to lose such a good letter writer so soon—believe me!

After the war Larry Lattimore wrote:

Oh yes, Agolsheim, did you know that was the second big attack in which I had acted in the capacity of C.O.? Golly! But after things finally quieted down, I enjoyed that little town. That was the first time we ever had any fun on the Rhine River. About that big white goose—we did cook it, we did eat it, and it was good! Do wish Col. Chaney had let you stay long enough to have some. Do you remember that little courtyard in front of my C.P.? About 15 minutes after you left, three 120 MM mortar shells landed in the center of that courtyard. Lucky no one was hurt but those shells sure shot hell out of our rations. I shudder to think what would have happened had those shells come in while you were still there. C’est la Guerre!

To return to Chapter 1: https://mollymartin.blog/2024/11/04/my-mother-and-audie-murphy/

Ch. 55: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/09/15/lt-david-waybur-honored/