They were feminist activists in the 1930s

My mother used to wonder aloud why my generation of girls and young women chose to hang out in co-ed groups. Why was there so much pressure to be with boys? She told me that as a young woman she’d had loads of fun communing with sisters in same sex groups. They invited boys to dances and events that they organized, but otherwise they sought the companionship of other women. Now, looking through scrapbooks she made in the 1930s, I can see what she was talking about.

My mother, Florence Wick, had graduated from Yakima High School at age 16 in the class of 1929½, just as the country sank into the Great Depression. She was planning to enroll at Washington State University (my alma mater) when the stock market crashed and ended her dream of going to college.  Instead she went to secretarial school. She got a job as a stenographer and worked steadily throughout the decade, living at home and supporting her family when her father lost his teaching job. In the 1930s my mother actively participated in women’s organizations that I now see set the stage for the feminist movement of the 1970s.

Instead she went to secretarial school. She got a job as a stenographer and worked steadily throughout the decade, living at home and supporting her family when her father lost his teaching job. In the 1930s my mother actively participated in women’s organizations that I now see set the stage for the feminist movement of the 1970s.

Flo was Biz-Pro president in 1936

Flo was Biz-Pro president in 1936While she could never afford college, she did join a sorority, Epsilon Sigma Alpha, which had been reorganized from a college group to include businesswomen. She was also a member and president of the Business and Professional Women’s Club (Biz-Pro) one of the “business girls” clubs that fell under the umbrella of the YWCA. These linked organizations provided opportunities for what we now call networking, but they also promoted the rights and welfare of workingwomen by sponsoring legislation for equal pay and to prohibit legislation denying jobs to married women. Founded to address the surge of women into the workforce during WWI, Biz-Pro still continues to advocate for workingwomen promoting equal pay, comparable worth and family leave legislation.

The sorority met twice a month, once for a study program and once for a social event. My mother saved programs and newspaper articles reporting on their events. Flo sometimes appears in the programs reviewing books (Stanley Walker’s Mrs. Astor’s Horse) or authoring skits. She participated in a bridge club and took home prizes. She directed a questionnaire on current event topics at one meeting. At another she reported on the biography of Nijinsky written by his wife. Politics was also on the agenda. On the Oct. 6, 1936 program, Miss Sylvia Murray presented a “Symposium of Nazism and Fascism.” Flo presented “Excerpts from Days of Wrath by Andre Malraux.” They had picnic summer potlucks. They played games. The local news reported: At the Thanksgiving party, 30 members and their friends were expected. The colors were yellow, orange and brown.

Smart cotton frocks of today’s vogue and demure fashions of 50 years ago vied for supremacy last evening when Epsilon Sigma Alpha sorority members entertained at a dessert bridge party in the Woman’s Century clubhouse. The sorority will have a horseback riding party as a feature of its next meeting, reported the local Yakima newspaper. In news articles the married women are referred to by their husbands’ names. A dinner and theater party were planned by sorority members at their meeting last evening in the home of Mrs. Malcolm Mays.

Bridge Tallies

Bridge TalliesThe Biz-Pro meetings, too, sought to combine business and pleasure.

Miss Edith Livingston had charge of decorating the tables with white cellophane Christmas trees, snowmen, blue streamers and white tapers. Girls made a contribution to the iron lung fund.

Despite their name, the business and professional women were not above movie stars and gossip.

Mrs. Gledhill, the former Miss Margaret Buck of Yakima, related interesting Hollywood anecdotes and described the YWCA work in the southern city. She particularly mentioned the Studio club in Hollywood where girls who are hoping for a “break” live and rehearse, “even tap dancers,” she says. Among board members are Mary Pickford and Mrs. Cecil De Mille.

Both my mother and I were active in the YWCA during the 1970s when its “One Imperative” was to “use its collective power to eliminate racism by any means necessary.” Together we attended the 1973 national conference in San Diego where the farmworker leader Cesar Chavez spoke. But I hadn’t realized how involved she had been in the YW during the 1930s. After its members demanded a focus on workingwomen at the 1910 world conference in Berlin, the YW’s objectives changed from protecting women from the vagaries of industrialization to promoting their equal inclusion. To this day the YW remains a worldwide force working against violence and supporting women, racial minorities, people with AIDS and refugees.

Flo represented Biz-Pro as a council member at its conference in Chicago in November 1937. A newspaper report of the meeting quoted her: “It was grand and I liked Chicago so much,” says Miss Florence Wick, all in one breath, of the National Business and Professional Women’s Council of the YWCA meeting in Chicago from which she returned this week. The article says of the 26 council members, she was the youngest (she was 24). The meetings were held in the McCormick residence in Chicago, a memorial to Harriet McCormick, an early supporter of the YW. “The loveliest building you ever saw,” according to Miss Wick. “I met so many notables in YWCA work, I feel so very insignificant,” Miss Wick remarks, laughing.

Flo as drawn by her teenage (biological) sister Ruth Wick

Flo as drawn by her teenage (biological) sister Ruth WickIn April 1938, she traveled to Columbus, Ohio to the national YWCA convention and later explained the “reorganization of the business girls’ groups” to her local chapter. She traveled around the Northwest to represent the local group along with others including her best friend and my namesake, Molly (Mildred) Hardin, another single workingwoman. By that time they called themselves the “Business and Professional and Industrial Girls.” Industrial referred to women who worked in factories and plants, as opposed to the “business girls” who worked in offices.

Flo told me she had accepted that she would be an “old maid” when, at 33, she met my father. Still working as a stenographer, she had assumed the identity of “career girl.” Her sister Eva, my aunt, told me Flo was always popular. She had lots of boyfriends but she was in no hurry to get married. She enjoyed the independence and self-esteem that came from earning her own living as a workingwoman. And she thoroughly enjoyed the rich friendships and associations she cultivated in the women’s organizations she joined.

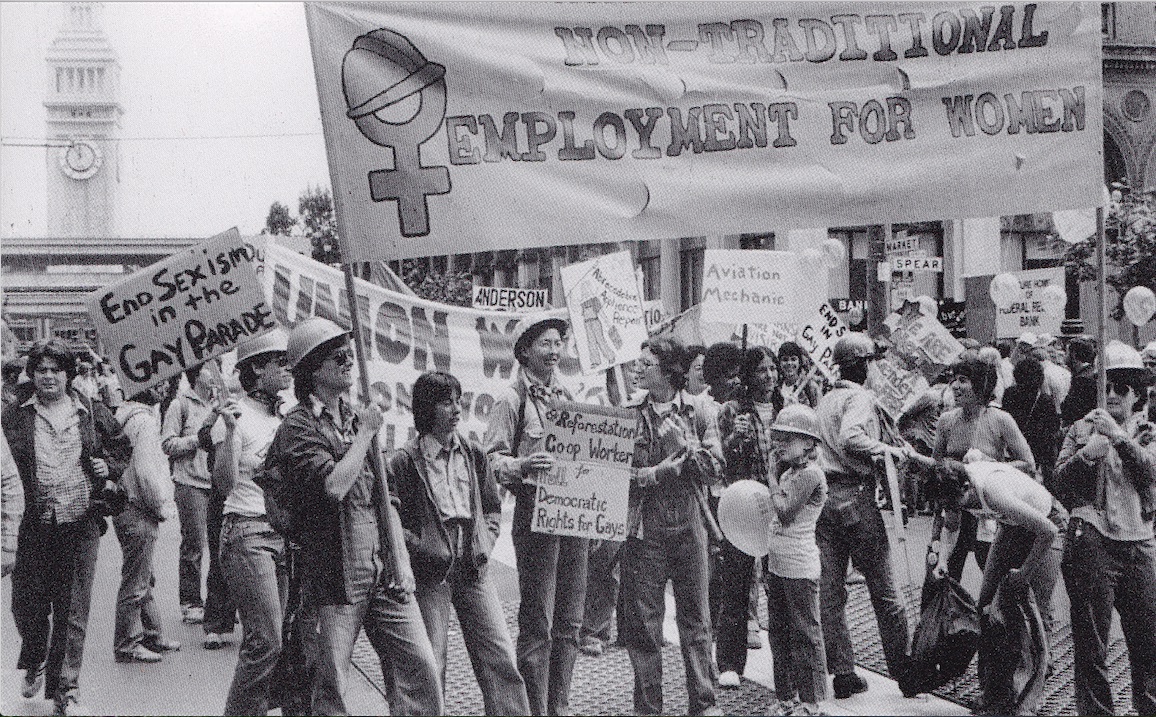

ay Area activists first formed Nontraditional Employment for Women (NEW) as a project of Union Women’s Alliance to Gain Equality (Union WAGE), a nonprofit organization for working women which included housewives, unemployed, retired, and women receiving welfare.

ay Area activists first formed Nontraditional Employment for Women (NEW) as a project of Union Women’s Alliance to Gain Equality (Union WAGE), a nonprofit organization for working women which included housewives, unemployed, retired, and women receiving welfare.

In 1979, Tradeswomen Inc., a 501c-3 nonprofit, was organized by a group of advocates including Madeline Mixer, director of District IX of the Women’s Bureau, US Department of Labor; and Susie Suafai, director of WAP. The goal was to access money to expand the already successful WAP project that was placing women in Bay Area union apprenticeship programs. For a short time, under President Jimmy Carter, construction jobs opened up to women. But after Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 everything changed. The Reagan administration immediately dismantled and defunded whatever affirmative action programs it could, and stopped enforcing regulations already on the books.

In 1979, Tradeswomen Inc., a 501c-3 nonprofit, was organized by a group of advocates including Madeline Mixer, director of District IX of the Women’s Bureau, US Department of Labor; and Susie Suafai, director of WAP. The goal was to access money to expand the already successful WAP project that was placing women in Bay Area union apprenticeship programs. For a short time, under President Jimmy Carter, construction jobs opened up to women. But after Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 everything changed. The Reagan administration immediately dismantled and defunded whatever affirmative action programs it could, and stopped enforcing regulations already on the books. Tradeswomen love a conference, an opportunity to get together and talk shop, share stories and revel in our community: a definite antidote to our typical working lives of isolation and otherness. We started convening even before we had jobs as we tried to figure out how to break into the world of “men’s work.” In the 1970s, tradeswomen organizations took root in communities all over the country, gathering women who wanted in the trades, women who had already muscled their way in, equal rights advocates, and a myriad of supporters.

Tradeswomen love a conference, an opportunity to get together and talk shop, share stories and revel in our community: a definite antidote to our typical working lives of isolation and otherness. We started convening even before we had jobs as we tried to figure out how to break into the world of “men’s work.” In the 1970s, tradeswomen organizations took root in communities all over the country, gathering women who wanted in the trades, women who had already muscled their way in, equal rights advocates, and a myriad of supporters.

See you at Women Building the Nation in Los Angeles May 1-3, 2015!

See you at Women Building the Nation in Los Angeles May 1-3, 2015!