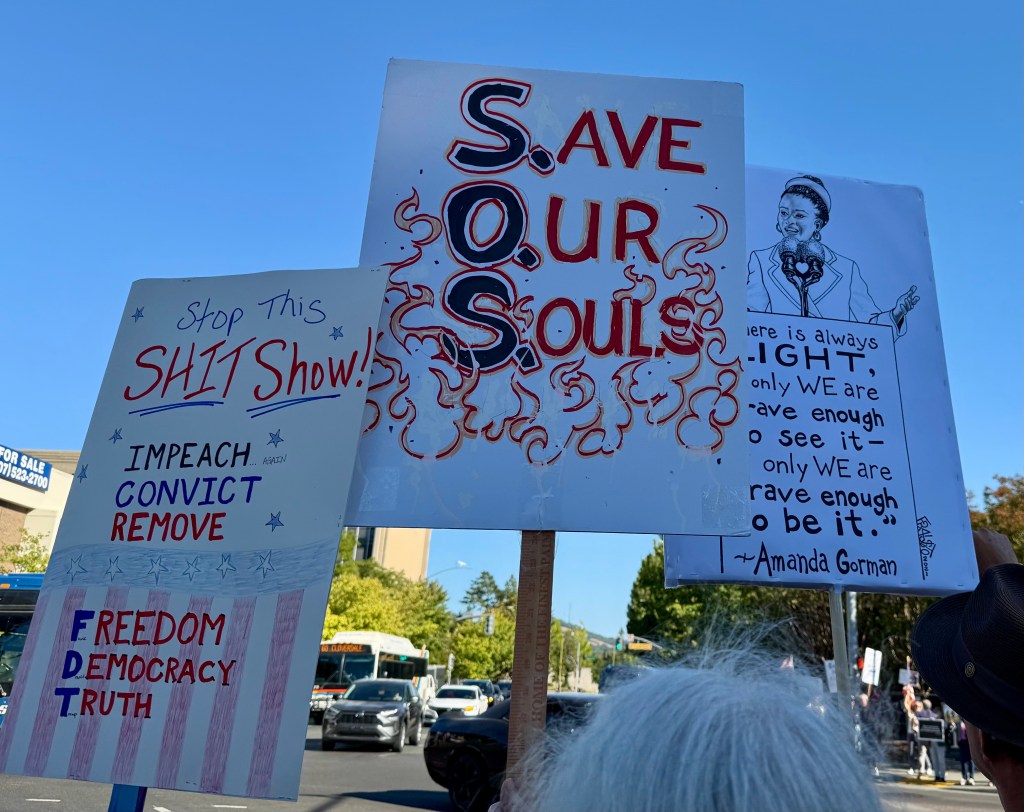

Marriage Equality Day in the Castro June 26, 2013

My Regular Pagan Holiday Post

National Girlfriends Day — August 1

August 1 marks the traditional Celtic holiday of Lammas, the first harvest festival on the pagan Wheel of the Year. According to the National Day Calendar, August 1 is also National Girlfriends Day. Judging by the ads, it might seem like a holiday invented to sell wine glasses and diet aids, but I plan to celebrate it anyway.

What does “girlfriend” mean in lesbianland?

In lesbianland, the word girlfriend carries a lot of weight, and a lot of meanings. It can refer to a platonic friend, a lover, or something in between. Back in the day, it usually meant lover. There simply weren’t enough words to describe us dykes or the nuanced ways we related to each other. For a while, we adopted partner, but that often got confused with business partner.

Very few of us used the word wife, and I never liked it.

As a budding feminist, I wanted no part of marriage. Wives, in my mind, were helpmeets, baby factories, second-class citizens. Property. In some states, it was still legal to kill your wife for adultery. Spousal rape wasn’t outlawed. Until 1974, women in the U.S. couldn’t even get credit in our own names. Before that, we had to depend on husbands.

The feminist movement changed all that. But I still never wanted to be a wife.

Girlfriend. Partner. Wife. Spouse.

Some lesbian couples still use the term girlfriend. They let their friends know they don’t like the term wife and don’t use it to refer to each other. Others in my Boomer generation have come up with alternatives. One couple calls each other spouse and spice.

But I’ve become a wife convert.

I’ve been married twice. Maybe three times.

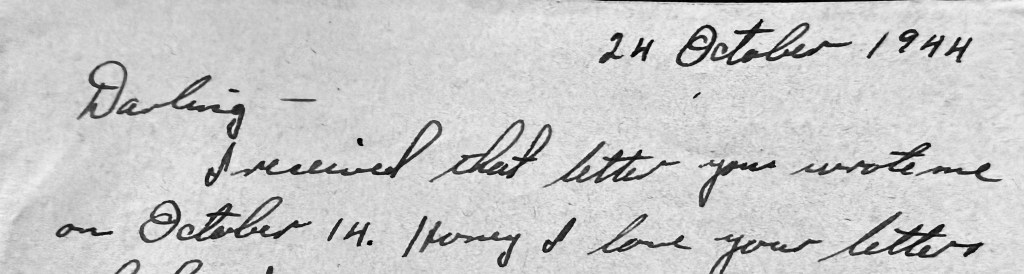

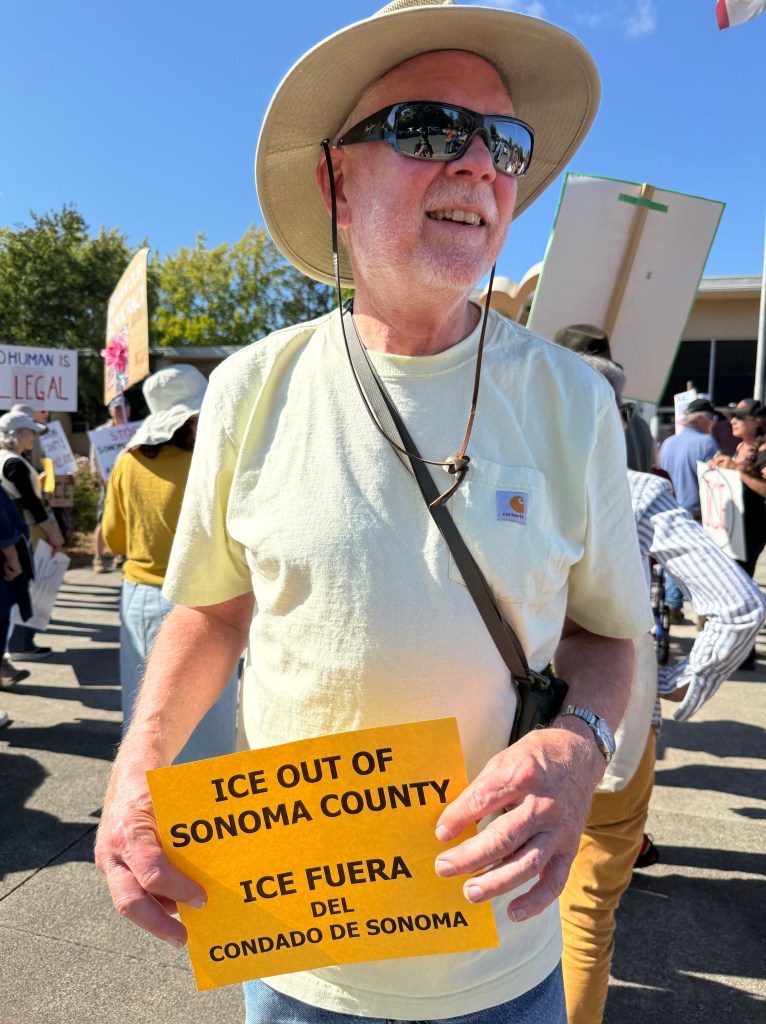

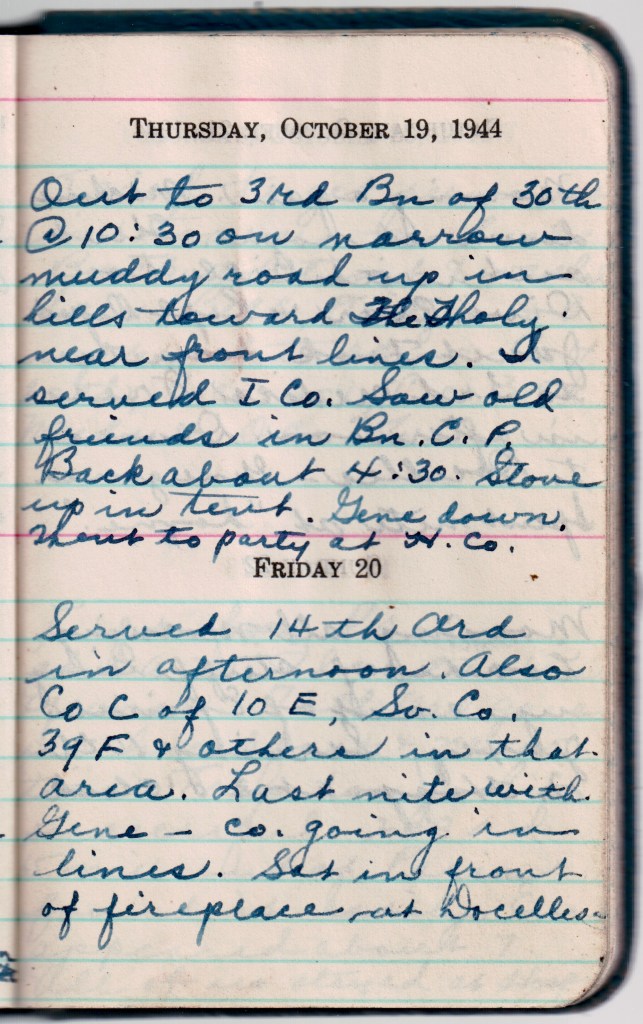

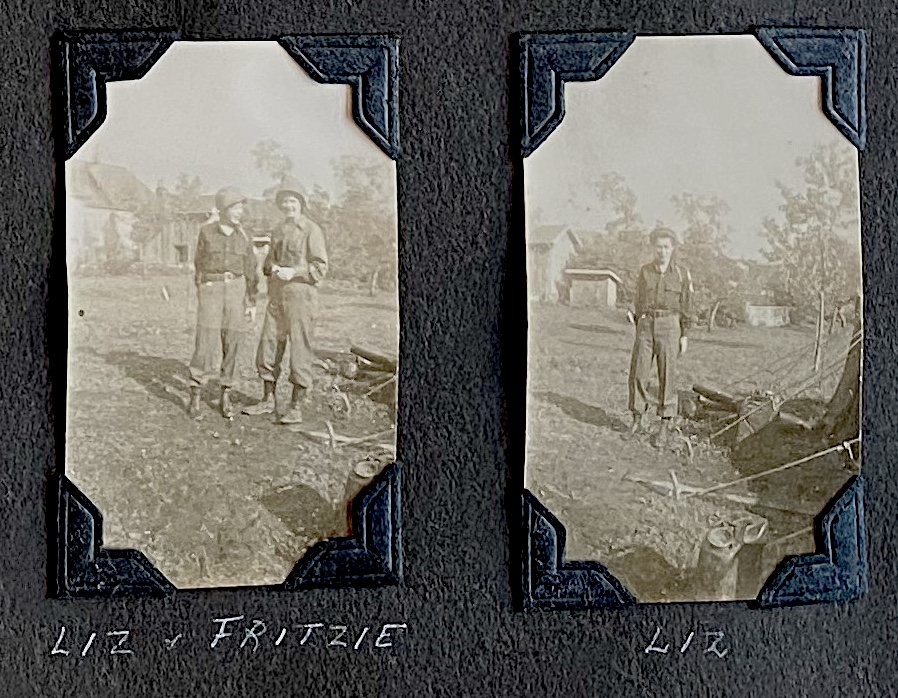

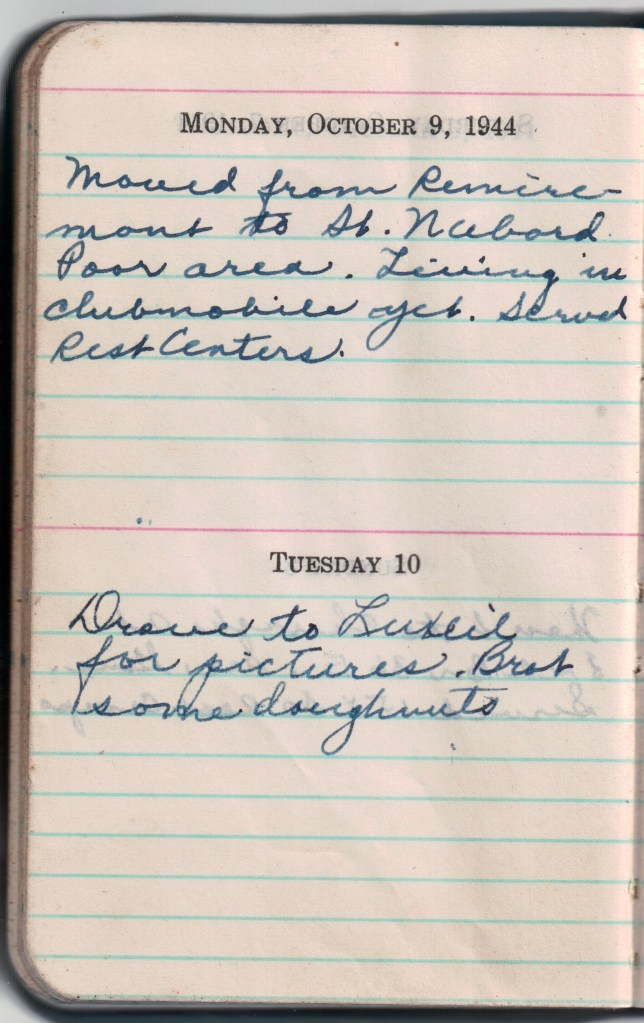

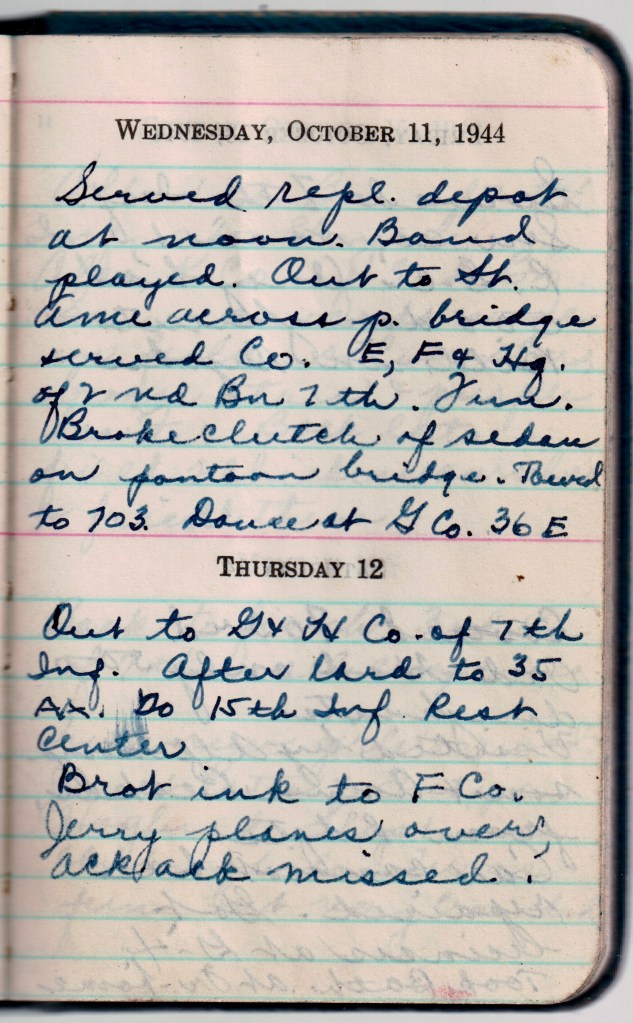

My ex, Barb, and I went to Vermont after it became the first state to legalize same-sex civil unions in 2000. But in 2004, San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom opened the doors to same-sex marriage. Thousands of couples–ourselves included–flocked to City Hall. Even though it wasn’t yet legal at the state or federal level, it felt revolutionary. Queer couples, dressed in their finest, stood in line all day in the rain, in the sun, waiting for a marriage license. Bouquets, cakes and good wishes arrived from around the country. The whole city felt like a wedding party. As City workers, Barb and I even got trained to be wedding officials ourselves. A lovely gender-free ceremony was provided.

Barb, then the San Francisco fire marshal, arranged for the SFFD chief, Joanne Hayes-White, to officiate our wedding in City Hall. In every room, in every hallway, people were saying vows. It was beautiful chaos.

As we walked through the metal detectors and the guard called me “sir,” I turned to Barb and said, “Well, I guess I get to be the husband.”

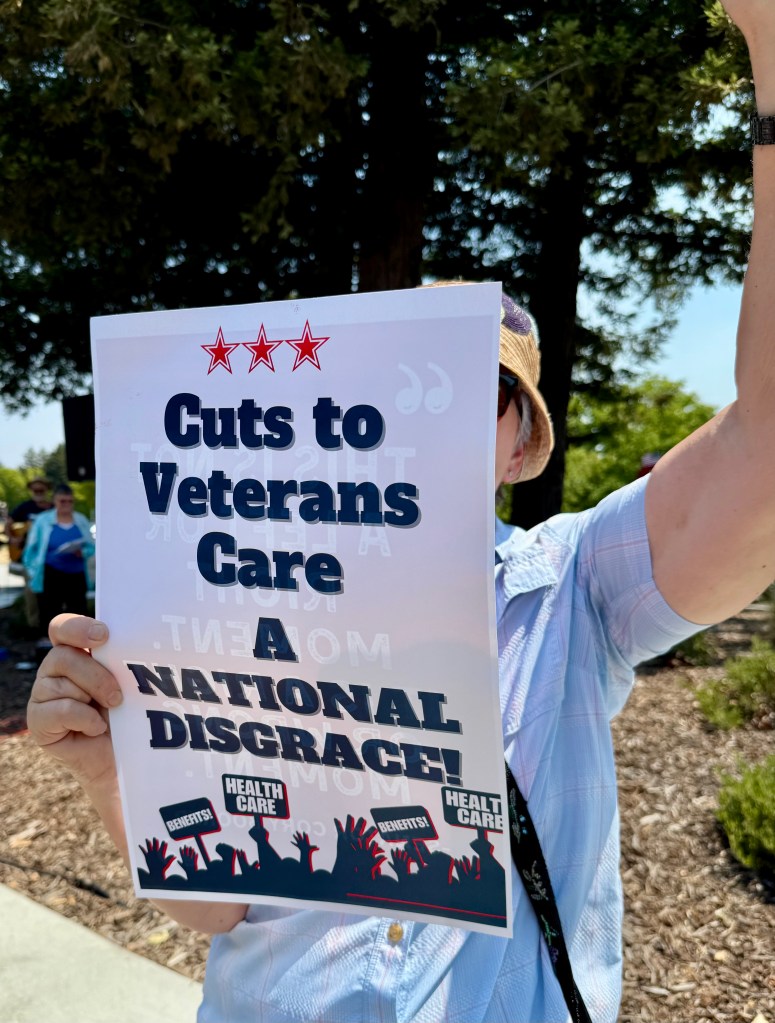

That was not fair. With her crew cut, she got misgendered as often as I did. Neither of us really wanted to be a wife. But in this country, being legally married means access to health insurance, tax benefits, hospital visits, and death benefits. There were–and still are–good reasons to marry.

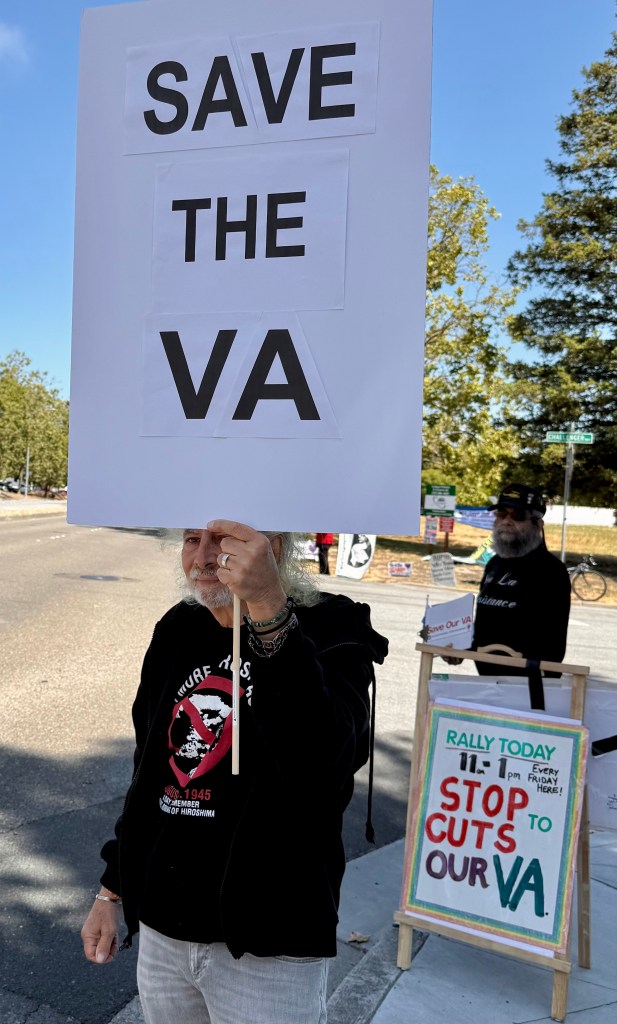

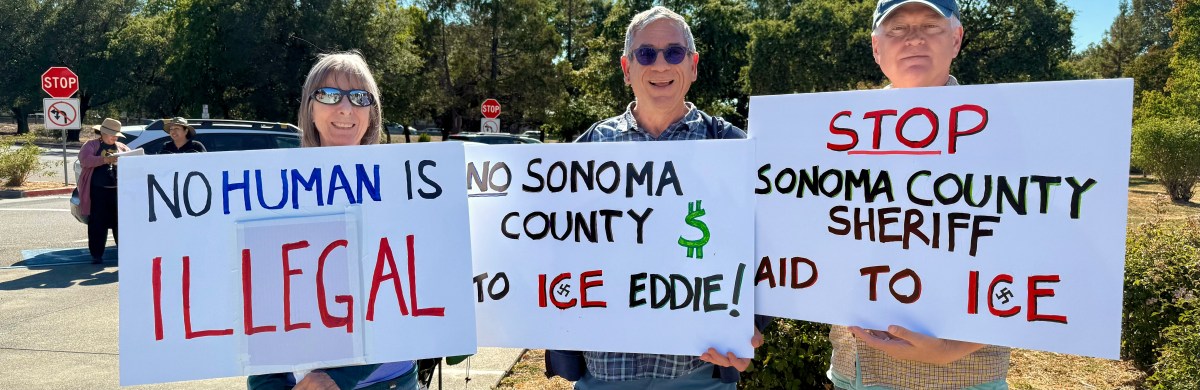

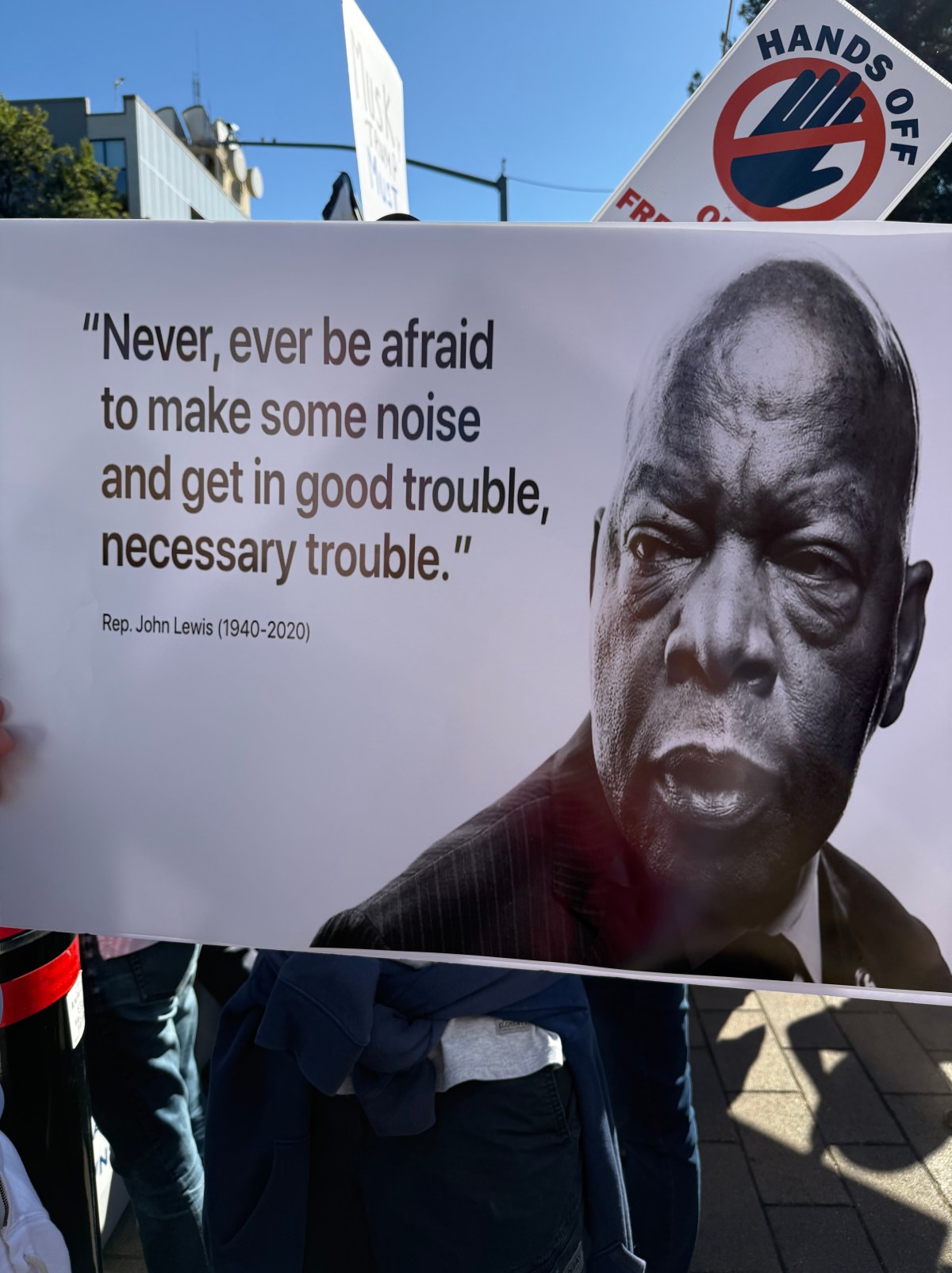

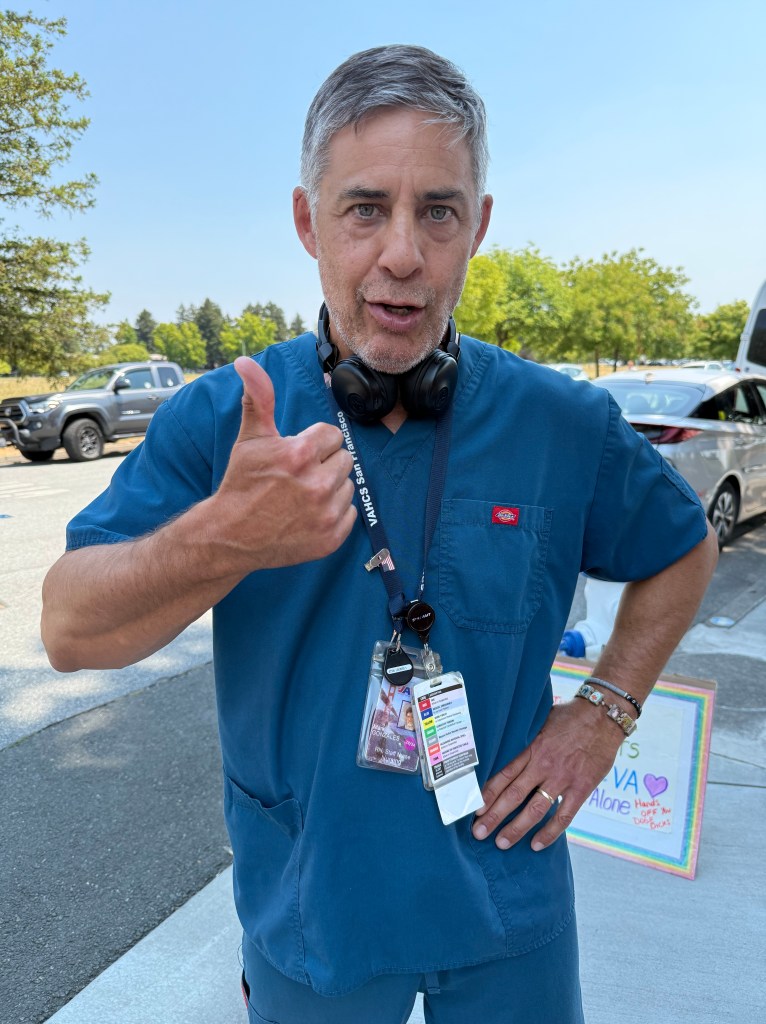

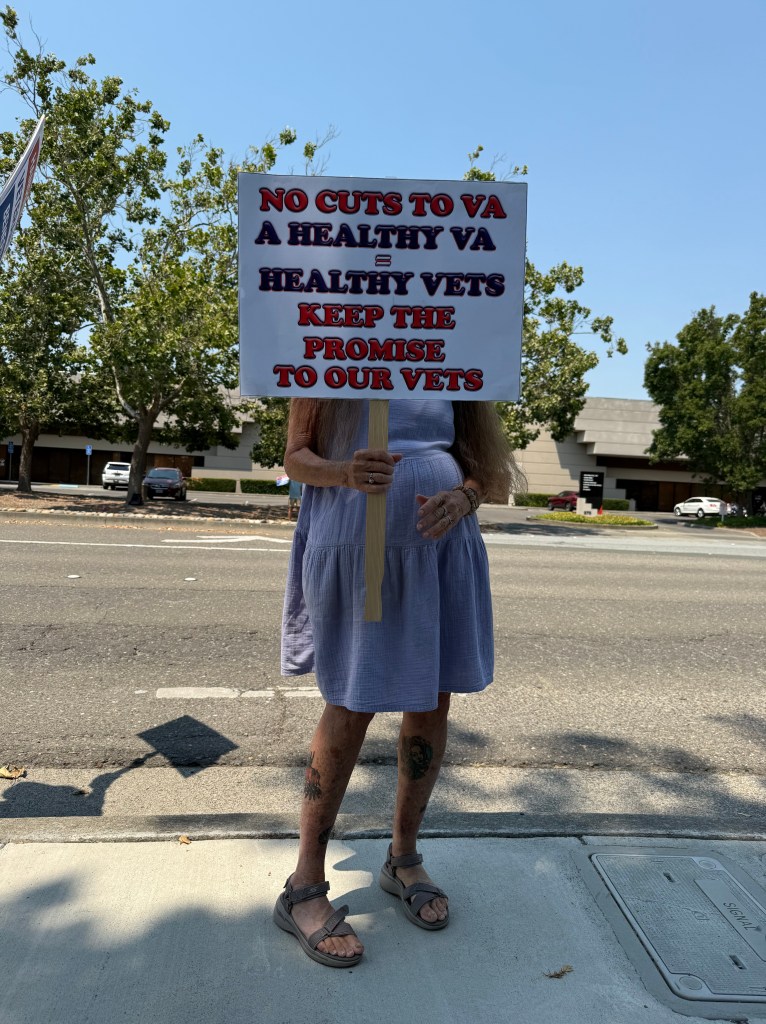

The road to legal gay marriage was long and convoluted, culminating with the 2015 landmark civil rights case Obergefell v. Hodges. But in 2013, United States v. Windsor overturned key parts of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), reinstating same-sex marriage in California. (Thank you, Edie Windsor!) By then, Barb and I had broken up. But because of legal limbo, we hadn’t been able to divorce. When the Supreme Court’s decision came down, we all ran to the Castro to celebrate. People held signs that said “Freedom to Marry.” For us, it was also the freedom to divorce.

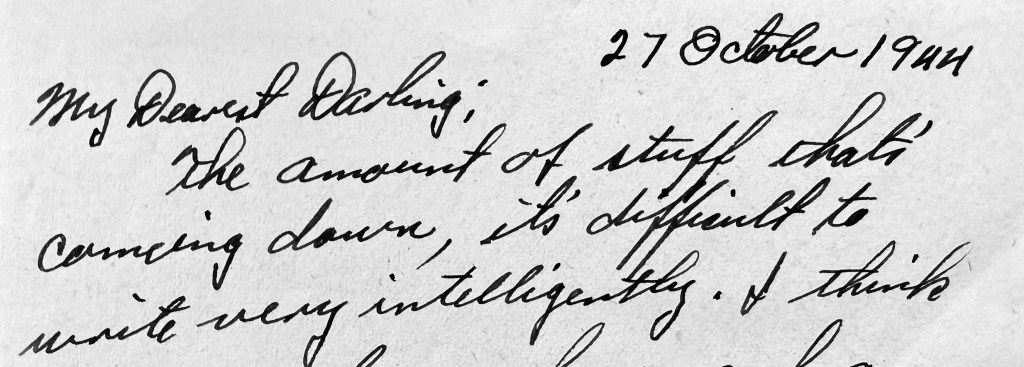

And then came Holly

Holly and I were married on April 19, 2014, at Muir Beach–the site of our first date. The wedding was officiated by our gay cousin Richard, dressed in the robes of his Episcopal priest friend who had been defrocked for gayness. Witnesses were my brother Don and his husband John.

I love introducing Holly as my wife. It’s a simple, meaningful word. A word I once rejected. And, frankly, it helps when talking to straight people, and still sometimes provides a bit of shock value. Everyone knows what wife means.

Oh, and for the record, we introduced our exes to each other. They got married too.

How to describe our relationships with each other? We call ourselves Exes and Besties. But you could call us a gaggle of girlfriends.

Happy National Girlfriends Day to all!