Chapter Two

Among the many questions I wish I could have asked my mother: When did you first have sex? Were you ever attracted to a woman?

We came of age at very different times. My mother turned 20 in 1933, the nadir of the Great Depression. I was 20 in 1969, the zenith of the Countercultural Revolution.

As close as we were, there were things her generation just didn’t talk about—private things. My generation talked about everything, even things that probably should have been kept private.

Whether or not my mother was ever attracted to a woman, I have found evidence that at least one woman was attracted to her. After I discovered the letters from Edna L., my mother’s ardent admirer, I searched in vain for her last name and any identifying information in Mom’s scrapbooks. They had roomed together in the Neil House Hotel in Columbus, Ohio for the national YWCA convention in April 1938. But “Eddie” (as she often signed her name) suggests in one note that they had met the previous year at a YW conference in Chicago.

“It has been fun to continue our friendship begun in Chicago (or even earlier) and I hope we shall be friends far into the future,” wrote Eddie.

I can’t imagine what Eddie means by “even earlier.” I didn’t think Flo had traveled east from Washington State before the Chicago trip, but I have one piece of evidence that suggests otherwise. She gave me a small painting and wrote on the back, “Bought at Dayton’s in Minneapolis in the 1930s. Sent to daughter Molly in San Francisco 2/82. Flo Martin.” So perhaps there had been previous meetings where they connected that Flo had not recorded in the scrapbooks. Had Flo and Eddie schemed for a year to room together in Columbus? They must have planned ahead at least.

So, my new obsession: Edna L. Reading her love notes to Flo warmed my heart and I began to identify with Eddie who slyly references “baths” and late-night “tuckin’ in” (her quotes, not mine). From reading her notes, I conclude she wanted to seduce my mother. Did she?

Some things I know about Eddie: She lived in New York. She was participating in the YWCA conference, so she could have been active in a Business and Professional Women’s Club, as was Flo, or in the YW. Chances are that Eddie was older than Flo, who was only 24 when they roomed together in Columbus. One clue I found in Eddie’s letters: they are literate with perfect spelling and punctuation. This suggests that she worked in an office and not a factory.

What did she look like? My mother’s scrapbooks from the 1930s are filled with pictures, but as far as I can tell there are none of Eddie or the YW conferences. But who knows? Flo didn’t caption anything in these early scrapbooks. In trying to imagine how Eddie looked, I could not even assume that she was white. Even in 1938, the YW strove to include racial minorities.

Participating in these conferences must have felt to my mother and her comrades like early feminist gatherings did to my generation of feminists. The meetings were focused on making institutional changes to give women and minorities more comprehensive rights. These women were leading a movement for social change, just as we did. The artifacts Flo saved in her scrapbooks show that many of these women built loving friendships with each other. The warmth expressed in their greetings illustrates deep feeling. From receipts she saved, I see they sent flowers to each other as thank yous, a practice I wish in retrospect my generation of feminist activists had adopted.

The Columbus conference was a continual round of meetings. In her love notes Eddie grumbles about not getting to see Flo back at the room until late at night.

“Aren’t we having a good time even though I have to sit up nights and wait for a chance to see you?”

“I certainly am enjoying being with you—even if I don’t have that opportunity ‘cept in the wee hours mostly, after I’ve tucked you in. I’ll be tuckin’ you in any minute now when you get back from your meeting on findings…”

Apparently the meetings went long into the night. Another participant noted, “Here’s to more 2am meetings.”

Flo had saved the banquet book from the YW convention and its inside covers were filled with inscriptions from attendees. Altogether there are 27 signatures. Nicknames were popular and they seem to have nicknamed Flo “Cricket.”

They all signed their full names, except Eddie who signed “Love—Eddie.” It’s an indication that their relationship was special, but disappointing for me because Eddie never signed her last name.

In the banquet book Eddie wrote: “Dearest Florence—You are one grand girl and a swell pal! These interludes of Council and Convention will always be happy memories because you shared them with me. I hope you’ll “bother” me “for years to come” and some day I’m coming to see you in the Northwest! Love—Eddie L.”

Did Eddie ever visit the Northwest? There is nothing in my mother’s scrapbook to suggest that she did. But items she saved show that Flo visited Eddie in New York in 1941. There are menus from the Swiss Village Inn and Struppler’s (next to the Cordova 917 Grand Ave.) I found a cocktail napkin from Jack Dempsey’s Broadway Bar and Cocktail Lounge, “Meeting Place of the World.” She kept a newspaper article citing record heat in NYC, a humid 91 degrees on the hottest Sept. 10 in a decade. There’s also a receipt from Sweden House Inc. (Swedish decorative arts) at Rockefeller Center for $1.53 dated 9/10/41, and a receipt for a single person at the Taft Hotel, 7th Ave at 50th St. NYC, and a menu from the Taft Grill.

The Taft Hotel, a 22-story high-rise built in 1926, was one of New York’s premiere tourist hotels with 2000 rooms right on Times Square at Radio City in Midtown. My mother, a small-town gal from Yakima, Washington, must have been thrilled to stay in such a glamorous big city accommodations. I bet she had a great view from room 1045.

How could my mother afford this trip? Had she been saving pennies for three years while working full time and helping to support her family? I could never afford to stay in hotels as a young working person, nor could my family afford hotels when I was growing up. On vacations we drove to the Cascade Mountains and pitched a tent. When I traveled I always arranged to stay in the homes of friends or comrades. It made me wonder if Eddie had chipped in to pay for the room at the Taft Hotel. Or maybe Eddie sprang for the hotel while Flo paid for the train trip. Perhaps she and Eddie had been corresponding furiously for three years, planning this tryst.

Flo also saved a Christmas gift card in its envelope from Macy’s New York. It is signed “With much love to you, Wickie dear—Edna L.”

There’s another note on a card with a monogramed L with no date: “My best love to a very good pal—Edna L.”

Then there’s a note that reads “Florence dear—Just got tickets for Watch on the Rhine—only chance it seems—Gertrude (my sister) will be joining us—will call you about meeting for dinner & theater tomorrow night. Edie L. (The play, by Lillian Hellman, won the New York Drama Critics prize in 1941).

Did Flo travel to New York just to visit Eddie? I can’t find any evidence of meetings of the YWCA or Biz-Pro in NYC in September 1941. Did she stay in a hotel and not with Eddie because she and Eddie wanted a place to be alone?

From the evidence, it looks like Flo travelled to New York by herself. In those days you could take the North Coast Limited on the Northern Pacific Railway all the way from Yakima to Chicago. Then you transferred to the Pennsylvania Railroad for the final leg to New York. Of course, by this time Flo was a veteran train traveler, having already been to Chicago, Columbus and Minneapolis.

As much as I’ve fantasized about my mother’s lesbian affair, I think the evidence is mixed. It wasn’t just that Flo had had lots of boyfriends, or that she married a man. That’s a story many lesbians tell. While I never married a man, I spent a decade experimenting with heterosexual sex before I came out.

My mother definitely struggled with homophobia. As liberal as she was politically, Flo had difficulty accepting that my brother and I are gay. He came out first and she felt justifiably burdened by the widely accepted Freudian theory that mothers are responsible for sons’ homosexuality. Then, when I came out a few years later, she at first chalked it up to a phase I was going though. Could that be because she went through a lesbian “phase” herself?

I made up all sorts of sensational stories about Eddie and Flo from the information I found in the scrapbooks. But since Eddie’s last name remained unrecorded, I gave up learning any more about her. Whatever happened between Flo and Eddie, I’m sure my mother had to wrestle with her own internalized homophobia and that of the dominant culture. At that time, in the 1930s, homosexuality was highly stigmatized and even in the big city of New York, lesbians stayed closeted to protect their jobs and reputations, meeting mostly at private house parties.

There remains the possibility that Flo was deeply in denial about her attraction/affair. I have some evidence to support this theory. My mother’s sister, Ruth, also had gay children and, while much more politically conservative, Ruth took a stand when her Presbyterian church excluded gays. She was proud of her gay kids and publicly quit the church in support of them. But she complained to me that she could never get my mother to talk about the issue. She couldn’t understand why Flo, her closest sister, had shut her out, especially with regard to a subject they both shared. I never understood this. I just assumed it had to do with Flo’s avoidance of the personal like so many in her generation, but perhaps my mother feared that her own sexual past would be revealed.

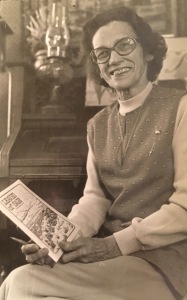

Did Flo have an affair with Eddie? I’ll never know for sure. If she were still alive, I think I could ask her now. When she died in 1983 at the age of 70, I still felt restrained from asking personal questions that I knew she would refuse to answer. Then again, maybe she never would have revealed the truth. She believed some things are best kept private.

Chapter 3 I find Eddie’s last name and more: https://mollymartin.blog/2016/11/27/i-find-eddies-last-name-and-more/