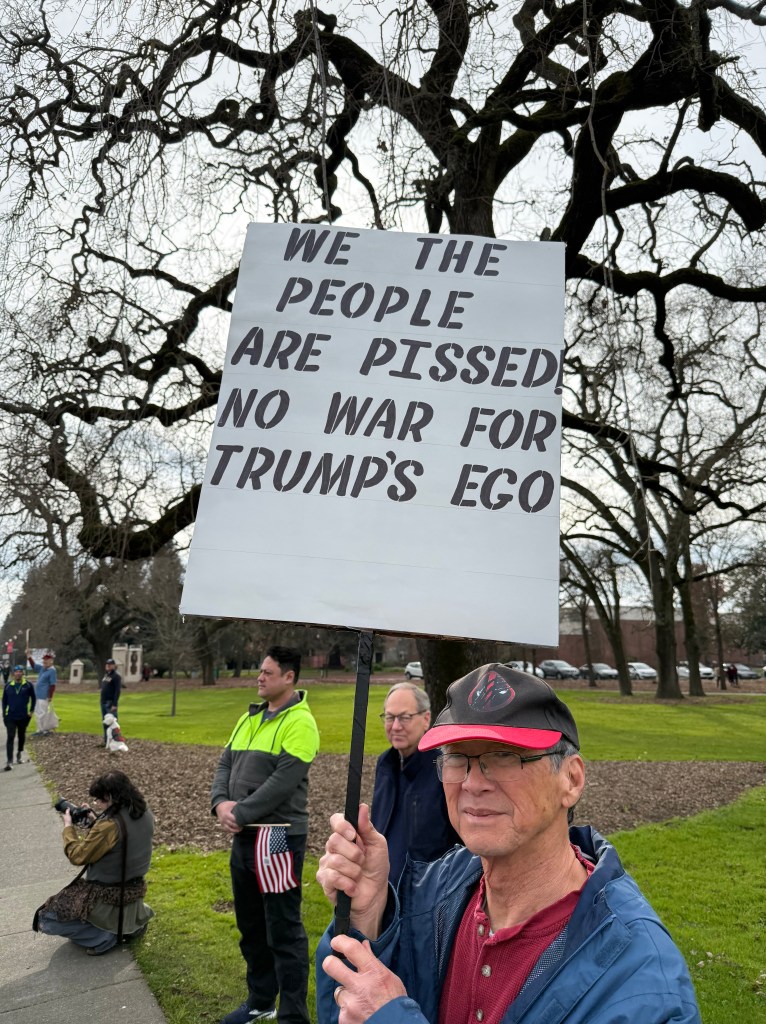

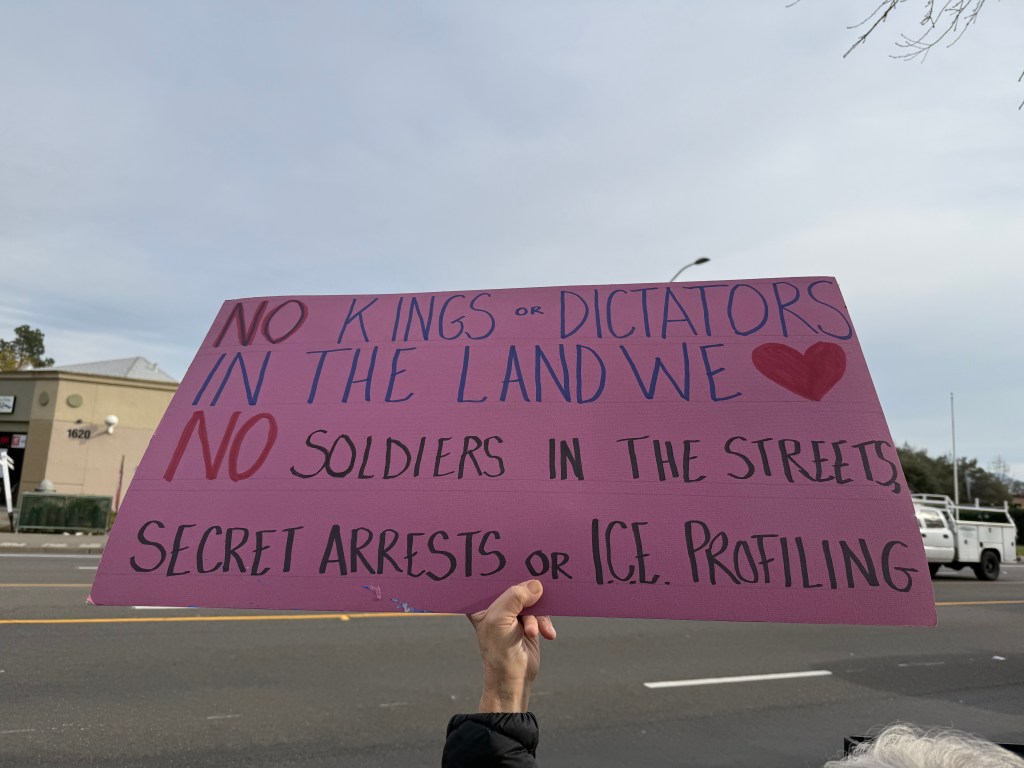

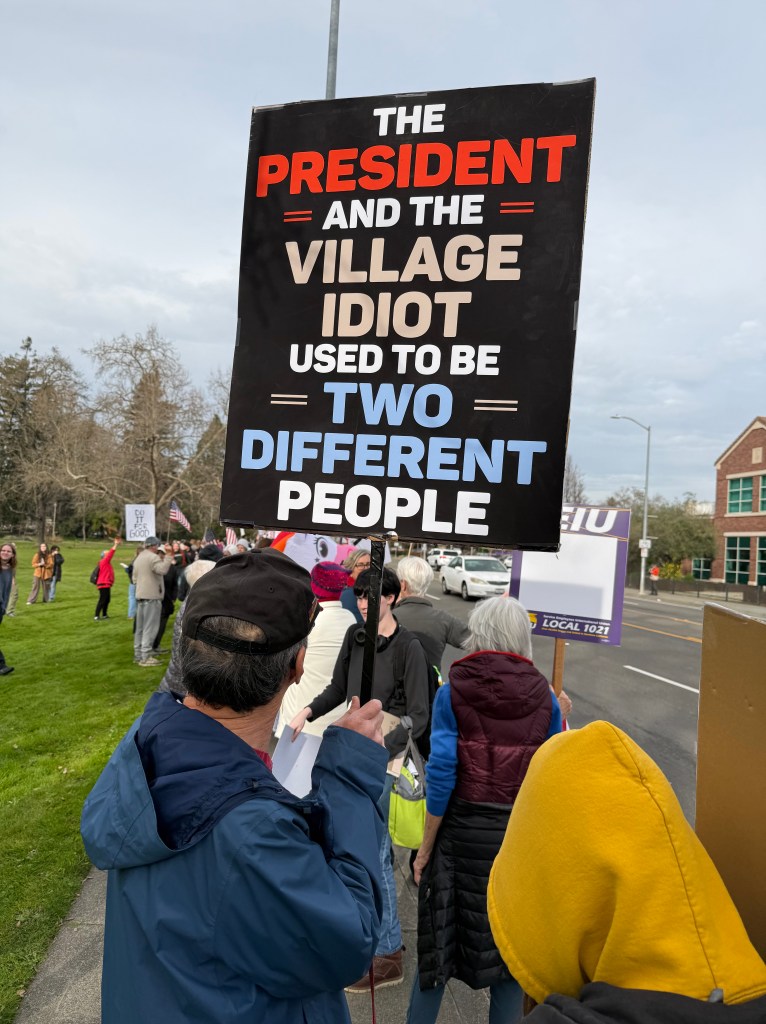

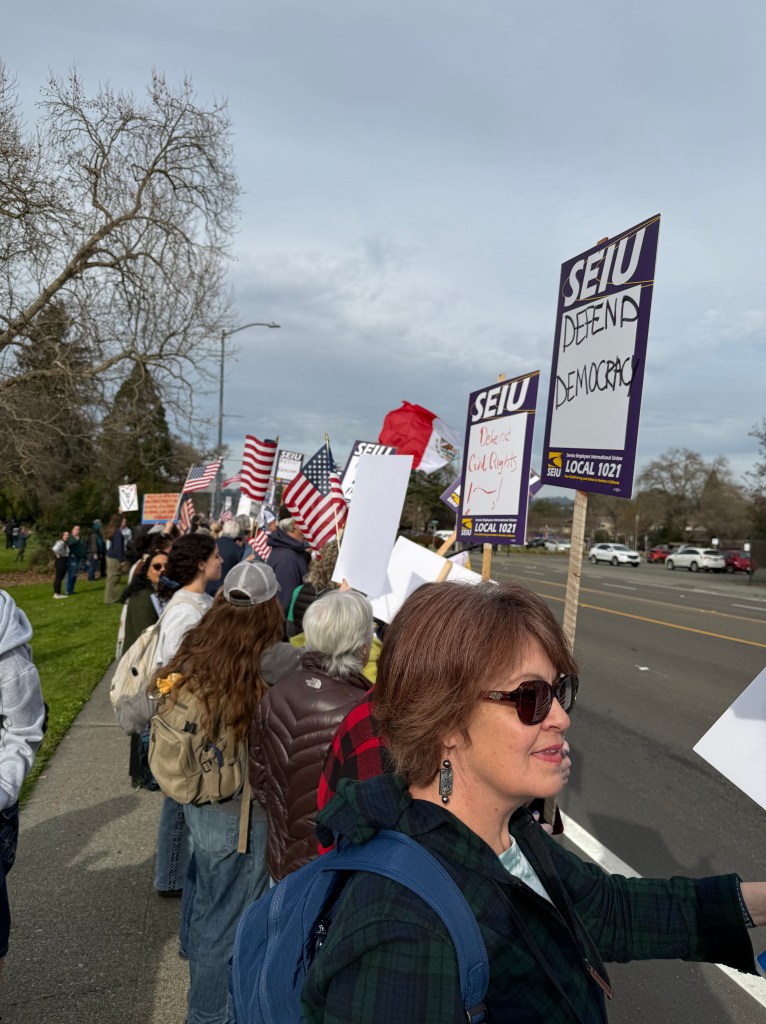

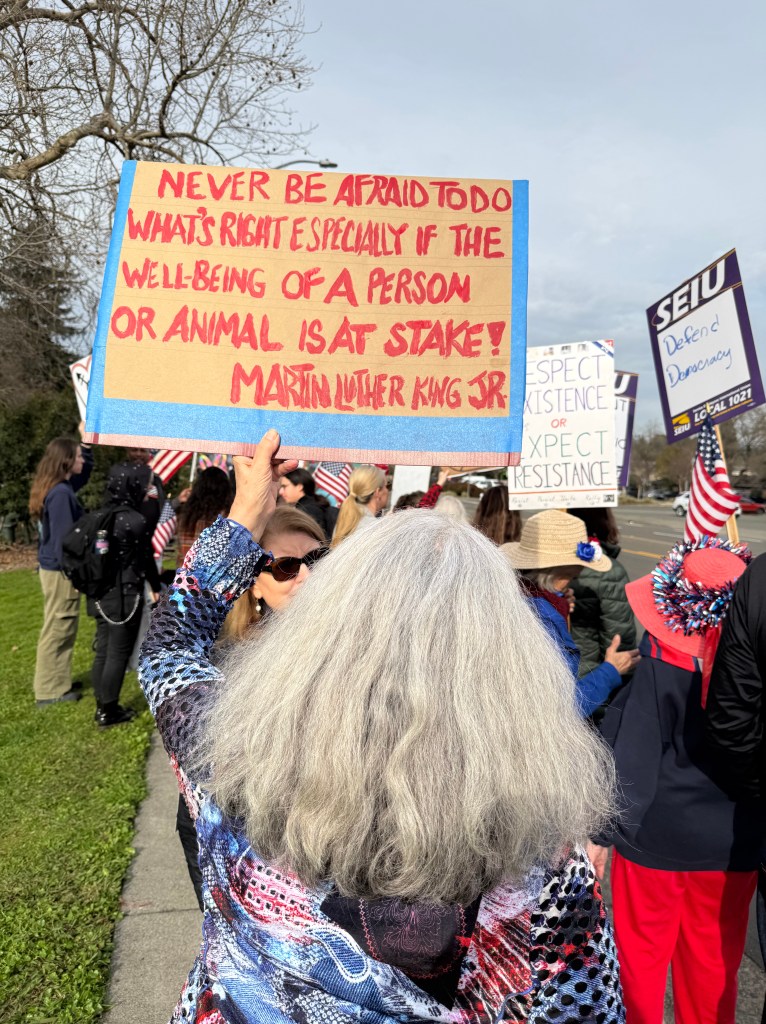

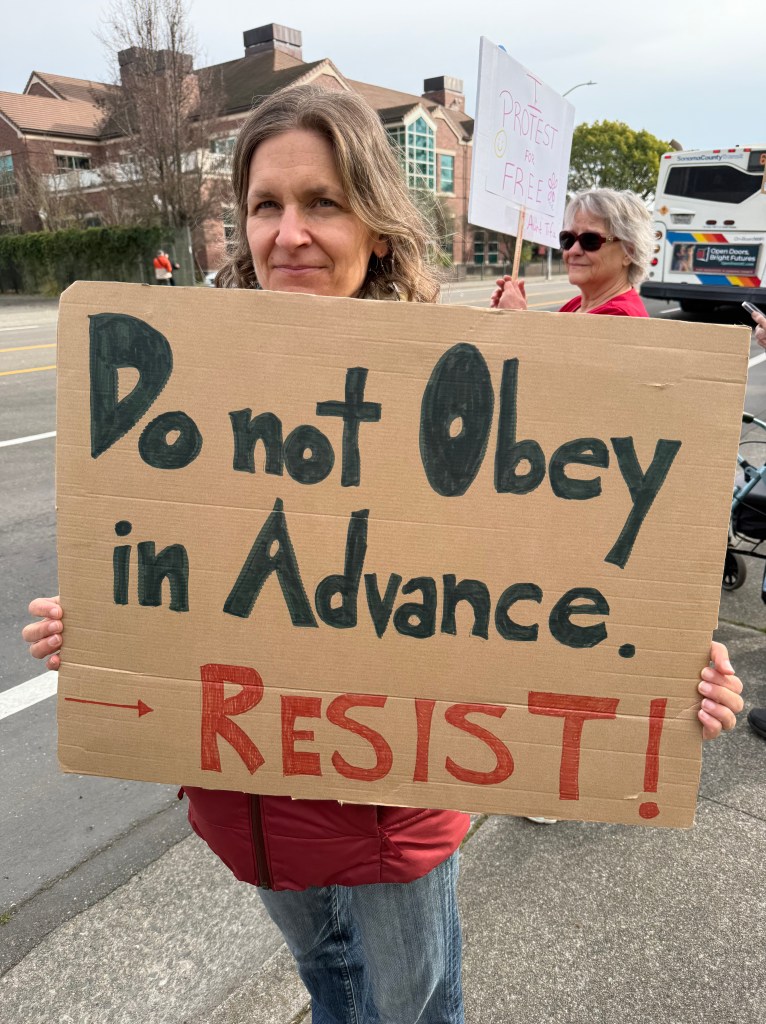

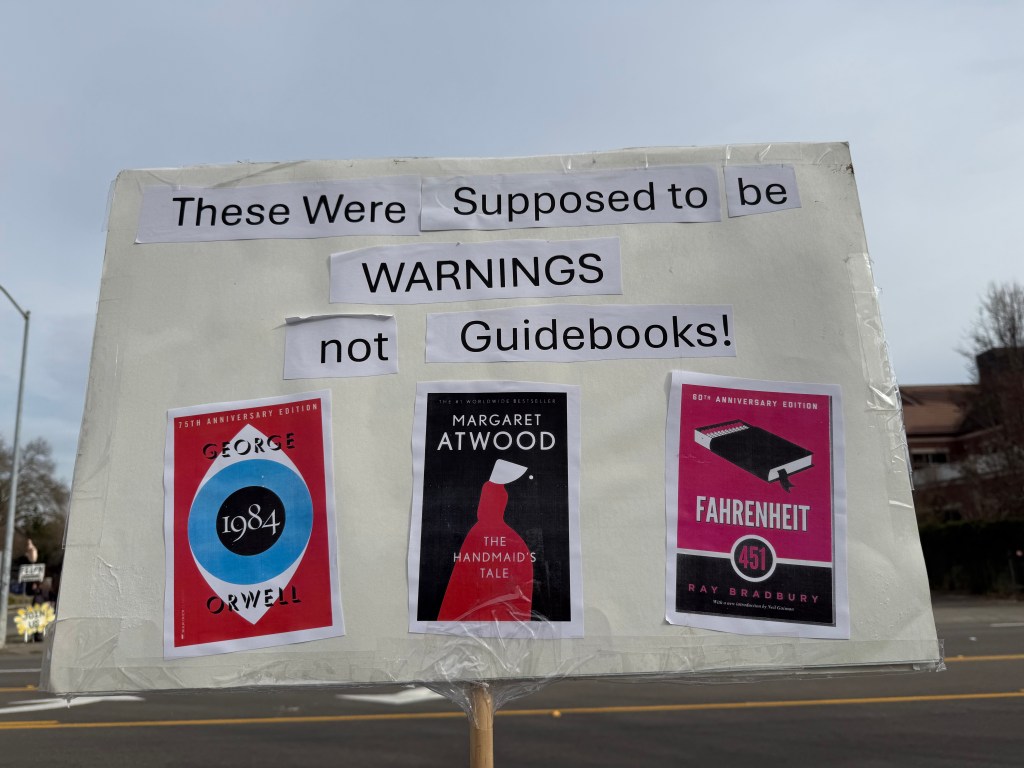

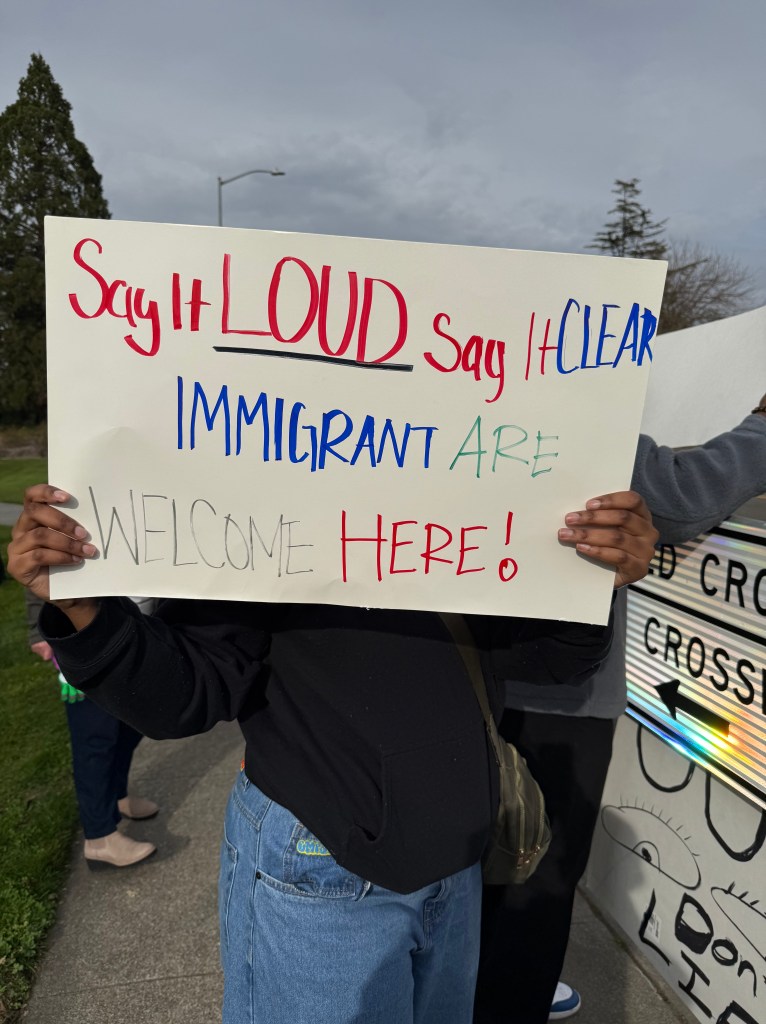

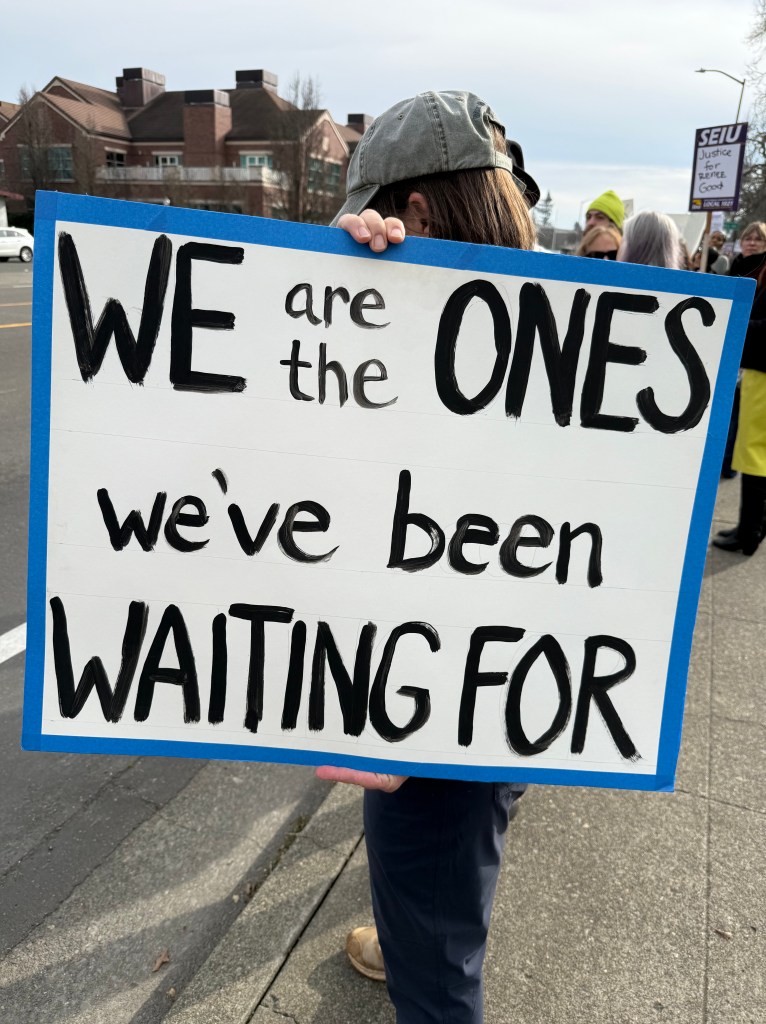

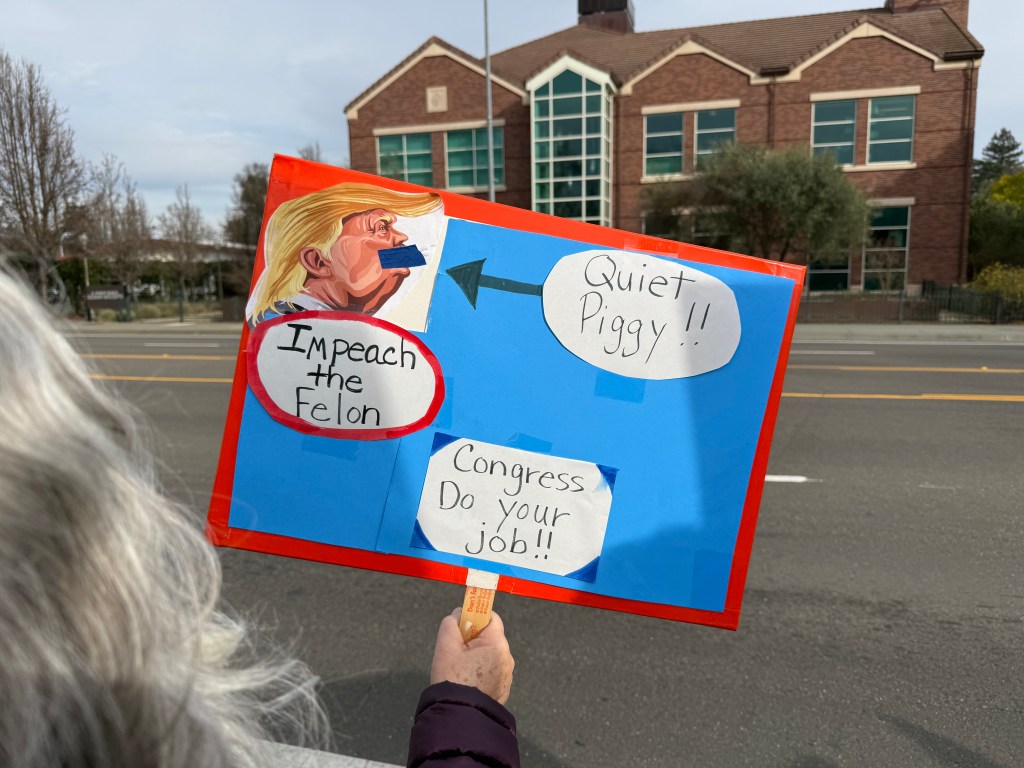

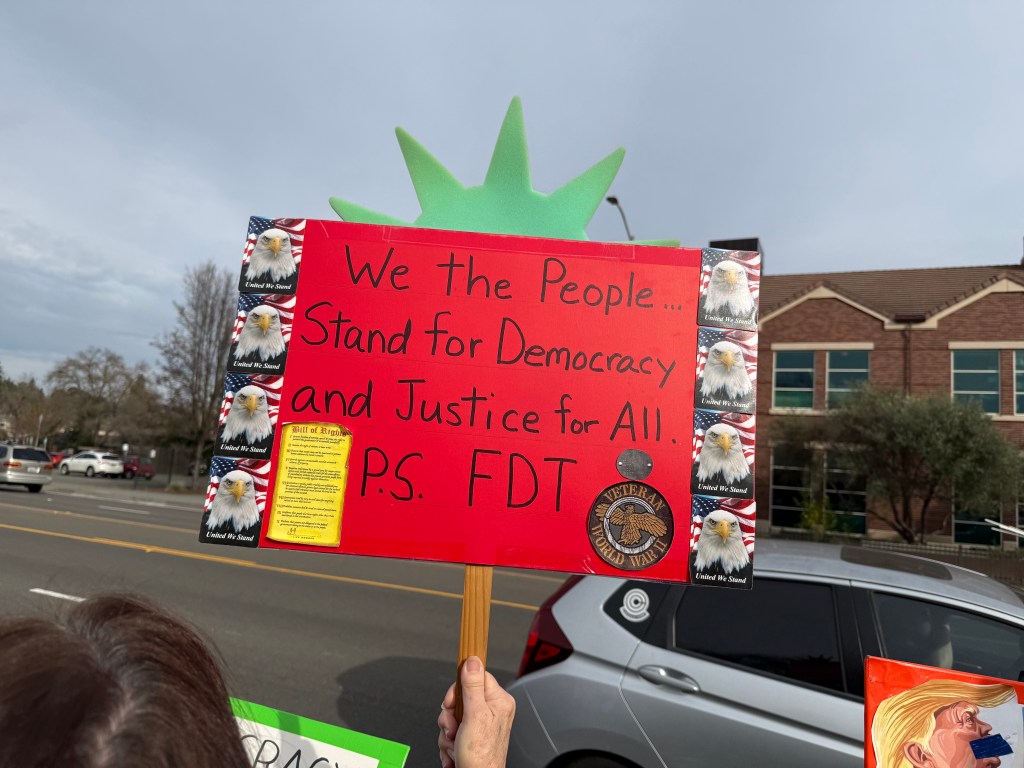

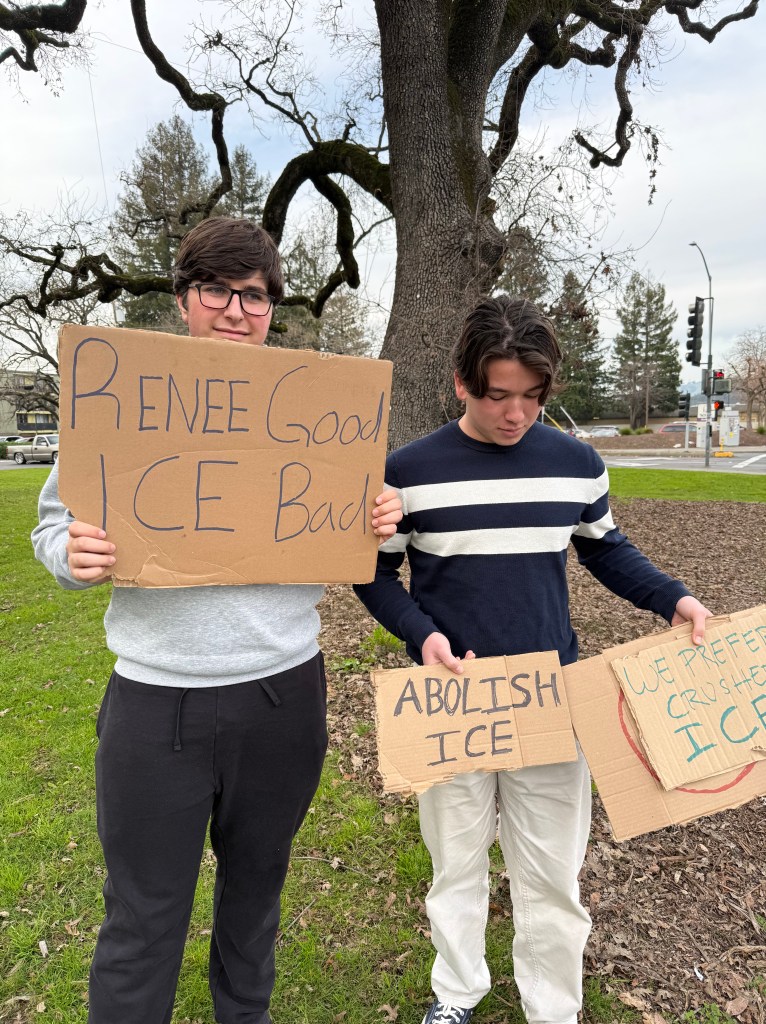

With Santa Rosa Women’s March and SEIU Local 2021

Folks Get Creative With Their Signs

Tradeswomen Reject Union’s Capitulation

Tradeswomn Inc. is a nonprofit I helped found in 1979. Still going strong, the organization helps women find jobs in the union construction trades. Here’s the text of a speech I gave October 30, 2025 at Tradeswomen’s annual fundraising event.

Sisters, we’ve come a long way.

When we first started Tradeswomen Inc., we had one goal:

to improve the lives of women — especially women heading households —by opening doors to good, high-paying union jobs.

It took us decades to be accepted by our unions.

Decades of proving ourselves on the job, standing our ground, demanding a seat at the table.

And now — by and large — we’re there.

We are leaders. Business agents. Organizers. Stewards.

We have changed the face of the labor movement.

But sisters, we are living in a dangerous time.

Our own federal government is attacking the labor movement.

And we cannot look away.

We all know that Donald Trump is gunning for unions.

Project 2025 is his blueprint — a plan to dismantle workers’ rights and roll back decades of progress.

Let me tell you some of what’s in that plan.

It would roll back affirmative action, regulations we worked so hard to secure,

Allow states to ban unions in the private sector,

Make it easier for corporations to fire workers who organize,

And even let employers toss out unions that already have contracts in place.

It would eliminate overtime protections,

Ignore the minimum wage,

End merit-based hiring in government so Trump can pack the system with loyalists,

And — unbelievably — it would weaken child labor protections.

Sisters and brothers, this is not reform.

It’s revenge on working people.

And yet, too many union members still vote against their own interests.

Why? Because propaganda works.

Because we are being lied to — by the media, by politicians, by billionaires who want to divide us.

That means our unions must do more than just bargain wages.

We must educate. Engage. Empower.

Because the fight ahead isn’t just about contracts

It’s about truth.

We women have proven ourselves to be strong union members — and strong union leaders.

We’ve built solidarity.

We’ve organized.

We’ve made our unions more inclusive and more reflective of the real working class.

And now it’s time for our unions to stand with us.

Many of our building trades unions have stood up to Trump, and to anyone who would divide working people.

But one union — the Carpenters — has turned its back on us.

The Carpenters leadership has disbanded Sisters in the Brotherhood, the women’s caucus that so many of us fought to build.

They have withdrawn support from the Tradeswomen Build Nations Conference, the largest gathering of union tradeswomen in the world.

They’ve withdrawn support for women’s, Black, Latino, and LGBTQ caucuses claiming they’re “complying” with Trump’s executive orders.

That’s not compliance.

That’s capitulation.

But the rank and file aren’t standing for it.

Across the country, Carpenters locals are rising up,

passing resolutions to restore Sisters in the Brotherhood

and to support Tradeswomen Build Nations.

Because they know:

You don’t build solidarity by silencing your own. And our movement — this movement — is built on inclusion, not fear.

While the Carpenters’ leadership retreats, others are stepping up.

The Painters sent their largest-ever delegation — nearly 400 women —to Tradeswomen Build Nations this year.

The Sheet Metal Workers are fighting the deportation of apprentice Kilmar Abrego Garcia.

The Electricians union is launching new caucuses, organizing immigrant defense committees, and they are saying loud and clear:

Every worker means every worker.

Over a century ago, the IWW — the Wobblies — said it best:

“An injury to one is an injury to all.”

That’s the spirit of the labor movement we believe in —and the one we will keep alive.

Our unions are some of the only institutions left with real power to stand up to the fascist agenda of Trump and his allies.

We have to use that power — boldly, collectively, fearlessly.

Because this fight is about more than paychecks.

It’s about democracy.

It’s about equality.

It’s about whether working people — all working people — will have a voice in this country.

Sisters and brothers, we’ve built this movement with our hands,

our sweat,

and our solidarity.

Now — it’s time to defend it. Together.

Solidarity forever!

Segregated Troops Encounter Racism, Show Courage

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 57

It’s easy to picture the American forces in WWII as all white. Wartime photographs, newsreels, and official histories rarely show otherwise. Flo’s own scrapbook from two years overseas with the American Red Cross and the Third Division contains no mention or images of Black soldiers.

Yet more than one million Black men and women served in the U.S. armed forces during the war. Their service was essential, though often invisible. Flo herself was no stranger to racial injustice—before the war she had been active in the YWCA’s anti-racism campaigns and in efforts to integrate the organization.

Historian Matthew F. Delmont, in Half American, argues that the United States could not have won the war without the contributions of Black troops. At the outset, however, the military tried to exclude them entirely. The Army, dominated by white supremacist segregationists, turned away Black volunteers after Pearl Harbor. Officials feared the political consequences of arming Black men. But as the war expanded, the need for manpower forced a compromise: a segregated military.

Many training camps were located in the South, where local white residents often harassed or assaulted Black soldiers. Abroad, Black Americans saw stark parallels between Nazi ideology and U.S. racial laws. The Pittsburgh Courier, a Black newspaper read nationwide, launched the “Double Victory” campaign—calling for victory over fascism overseas and victory over racism at home.

Segregated combat units fought bravely despite facing discrimination from their own commanders. The 92nd Infantry Division served in Italy beginning August 1944, possibly crossing paths with the Third Division. The Montford Point Marines, the 761st “Black Panther” Tank Battalion, and the celebrated Tuskegee Airmen also saw combat. Black soldiers fought and died at Normandy, Iwo Jima, and the Battle of the Bulge.

Most, however, served in unheralded but vital support roles. They built roads, hauled supplies, cooked, repaired equipment, and maintained the machinery of war. Seventy percent of all soldiers in U.S. supply units were Black. “WWII,” one historian wrote, “was a battle of supply,” and these troops kept that battle moving. There was even an all-Black American Red Cross contingent that ran segregated service clubs for Black troops.

The U.S. military and press often hid these contributions. Photographers were instructed to avoid showing Black soldiers in official images. When the war ended, Black veterans returning to the South were targeted for violence—beaten, harassed, and in some cases murdered—for wearing their uniforms. This had happened after WWI, and it happened again. Many veterans, like decorated soldier Medgar Evers, became leaders in the postwar civil rights struggle.

Alongside Black troops, the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team of Japanese American soldiers fought in the European Theater. Formed in 1943, the 442nd was made up largely of Nisei—second-generation Japanese Americans—many of whom had families incarcerated in U.S. internment camps. Beginning in 1944, they served in Italy, southern France, and Germany, becoming one of the most decorated units in U.S. military history.

The contributions of these segregated units—Black and Japanese American alike—were essential to Allied victory. Yet their service has been downplayed or erased from the dominant WWII narrative. Restoring these stories helps reveal a fuller, truer picture of the war that Flo witnessed.

Ch. 58: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/09/27/taking-a-break-in-nancy/

The 6888th Battalion cleaned up the mail mess

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 43

In October 1944, after her fiancé Gene was killed, Flo had trouble reaching her mother. The wartime mail system was broken.

This wasn’t just a personal problem—it was widespread. Soldiers on the battlefield were not receiving letters and packages from home. Mail, the lifeline of morale, was piling up undelivered. The men risking their lives for democracy weren’t hearing from their families, and the silence was taking a serious toll.

Flo had noticed the problem early. In letters and diary entries beginning in May 1944, shortly after arriving in Italy, she often mentioned that no mail had come. She didn’t complain—Flo wasn’t a complainer—but she noted it again and again. Others were more vocal. Across the war front, soldiers and Red Cross workers alike were frustrated and bitter. What began as a logistical issue had grown into a morale crisis.

The Army didn’t officially acknowledge the scale of the problem until 1945—by then, millions of letters and packages were sitting in European warehouses, unopened and unsorted.

Then came the 6888th.

The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion—known as the “Six Triple Eight”—was a groundbreaking, all-Black, multi-ethnic unit of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), led by Major Charity Adams. It was the only Black WAC unit to serve overseas during the war.

Their mission: clear the massive backlog of undelivered mail under grueling conditions and extreme time pressure. They worked in unheated warehouses, with rats nesting among the mailbags, and under constant scrutiny from a military establishment rife with racism and sexism. But they got the job done—sorting and forwarding millions of pieces of mail in record time.

Their work restored something vital: connection. And morale.

The 6888th wouldn’t have existed without the efforts of civil rights leaders. In 1944, Mary McLeod Bethune lobbied First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to support the deployment of Black women in meaningful overseas roles. Black newspapers across the country demanded that these women be given real responsibility and not sidelined. Eventually, the Army relented.

The women of the 6888th made their mark. Many would later say they were treated with more dignity by Europeans than they had ever experienced in the United States.

If you haven’t seen the Netflix movie The Six Triple Eight, it’s well worth your time.

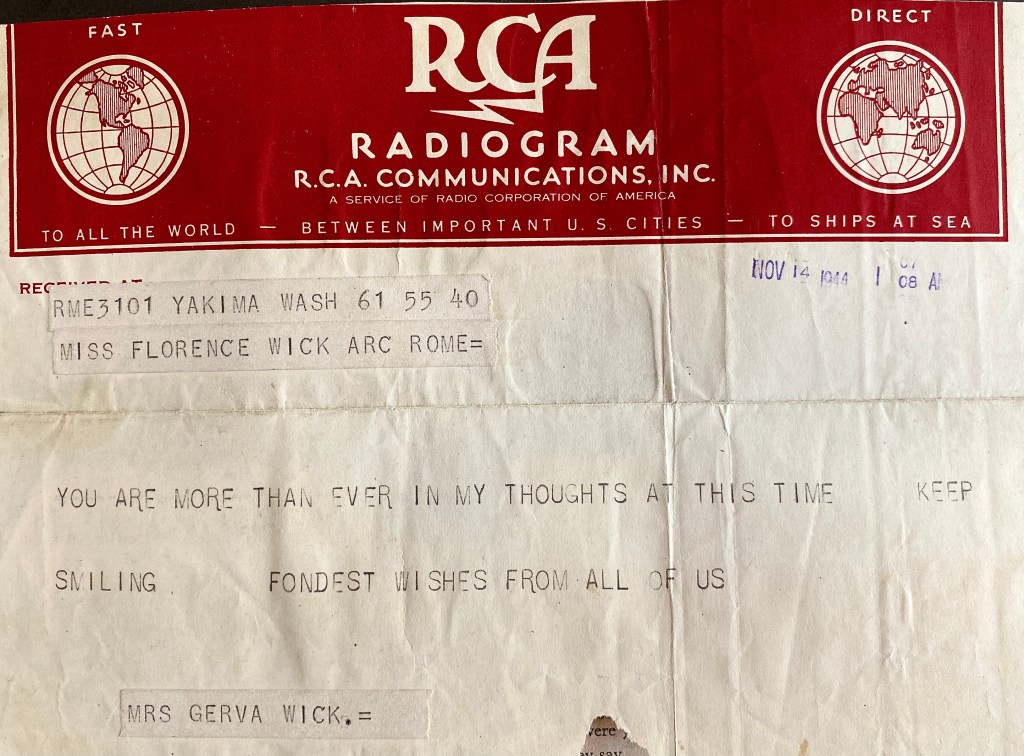

Back in October 1944, the broken mail system meant heartbreak and silence for Flo. How long did it take for her disconsolate letter to reach her mother? Gerda telegrammed back on November 14—more than two weeks after Gene had died.

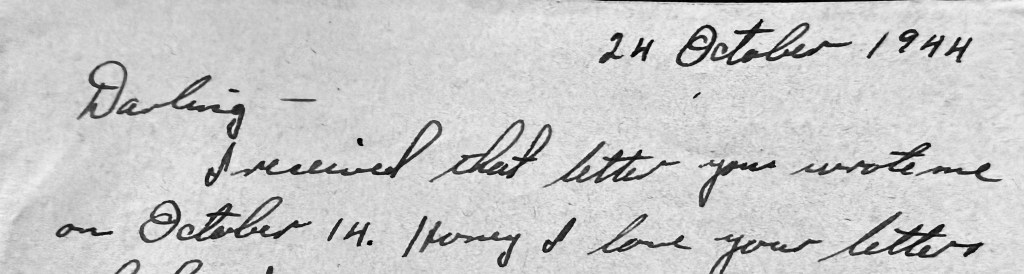

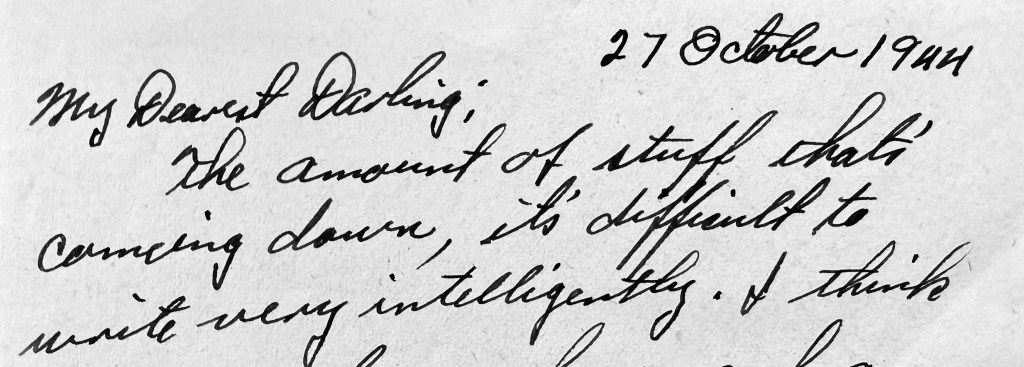

When did Flo receive Gene’s final letters? She saved the ones he wrote on October 24 and 27, but it seems likely she didn’t get them until after he was gone. He died on October 28, killed by a mortar shell. That same day, Flo wrote in her diary, “Mail from home today.” She didn’t mention anything from Gene.

In his last letters, Gene wrote about his army buddies. He worried about his little sister wanting to marry. He dreamed of peace, and of a life with Flo in the Northwest:

“Back there where the country is rugged and beautiful. Where you can breathe fresh, free air; and fish and hunt to your heart’s content. You know honey, a place where we don’t have to sleep in the mud and cold, and where the shrapnel doesn’t buzz around your ears playing the Purple Heart Blues.”

Even in the chaos of war, he tried to stay lighthearted:

“I’m writing on my knees with a candle supplying the light. I hope you are able to read it. My spelling isn’t improving very much; but with the aid of a dictionary I may improve or at least make my writing legible.”

He hoped Flo had managed a trip to Paris, and that she’d seen her sister and brother-in-law stationed there. He looked forward to getting married:

“Honey I haven’t heard from home on the ring situation yet, but I expect to before long. When I do, I shall let you know right away. I’m hoping we can make it so by xmas, if not before.”

But his letters also reflected the danger he was in:

“It’s very difficult to write a letter on one’s knees, as you probably already know. Ducking shrapnel and trying to write just don’t mix. I do manage to wash and brush my teeth most every day.”

“It’s too ‘hot’ for you to be here. I’ve got some real stories to tell you when I see you next—if I’m not too exhausted. You don’t know how close you’ve been to—I hadn’t better tell you.”

Gene’s voice comes through with vivid clarity, even across 80 years and a broken mail system.

That words eventually reached soldiers in the field and their families back home is thanks, in part, to the quiet heroism of the 6888th—who made sure love letters, grief, and hope could still find their way through a war.

Ch. 44: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/08/02/born-in-oregon-buried-in-france/

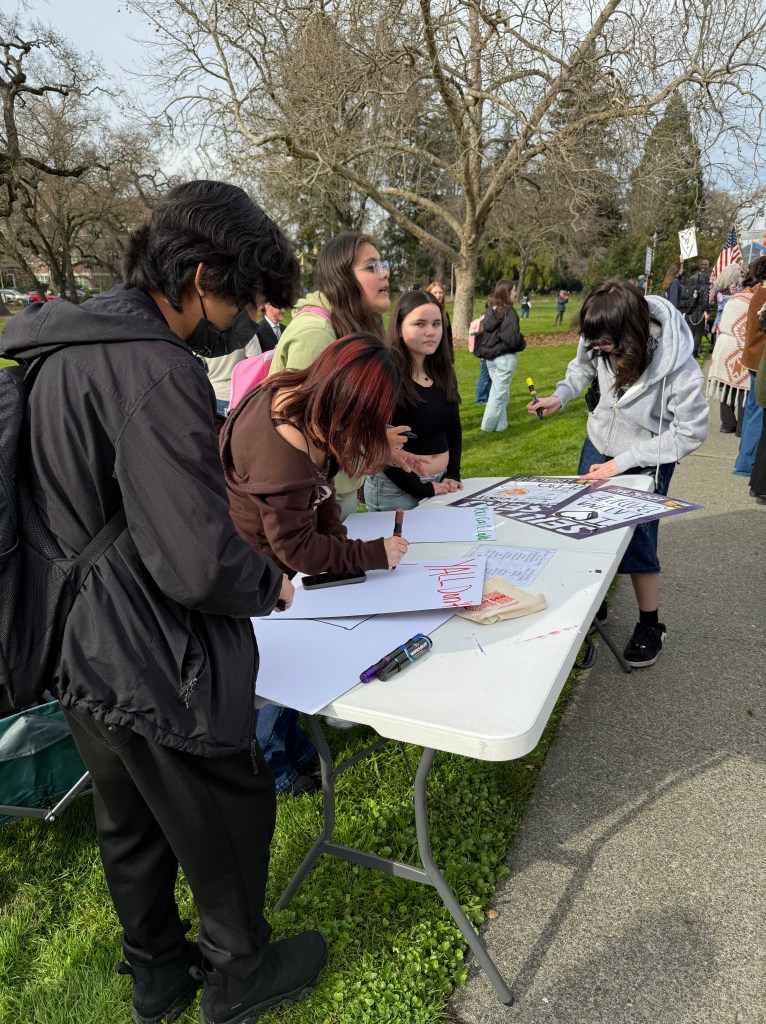

Neighbors Getting Ready for the Big Demonstration Saturday

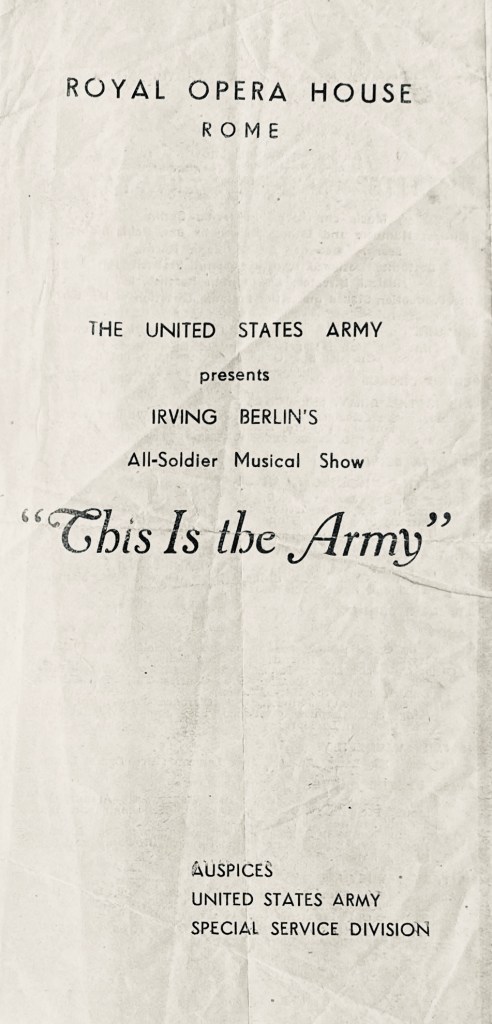

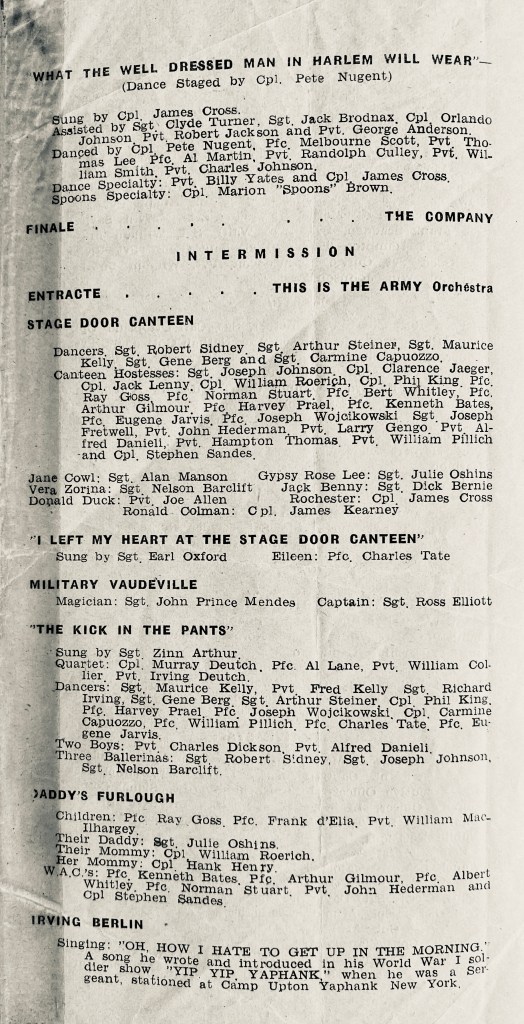

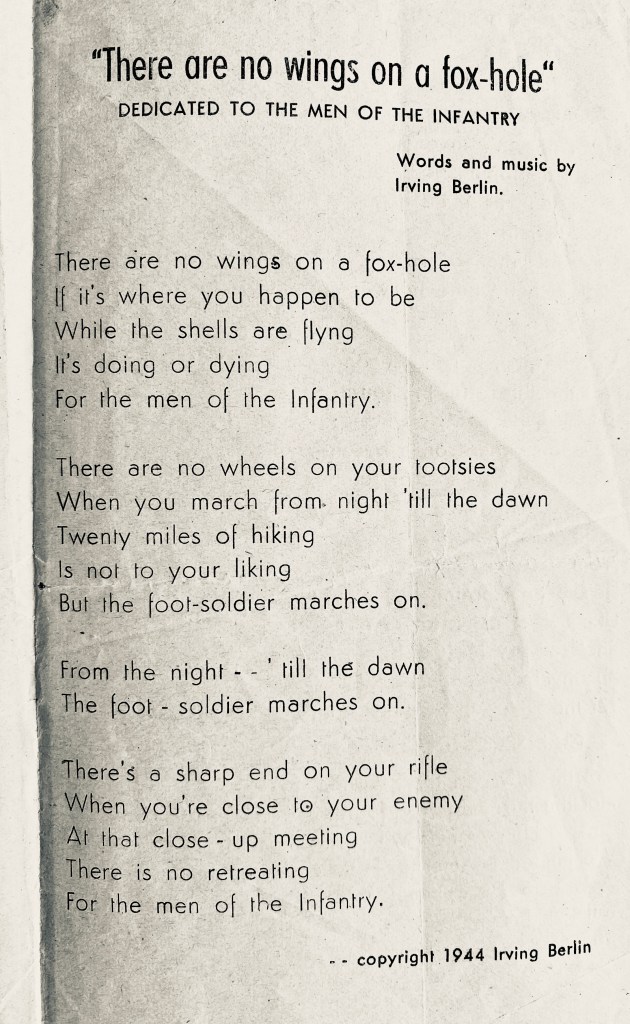

June, 1944. Flo saw This is the Army at the Royal Opera House in Rome

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 17

Drag, blackface, racial integration, “too many Jews”—they’re all part of the complicated legacy of Irving Berlin’s wartime musical revue, This Is the Army.

Berlin conceived the show in 1941, even before the U.S. entered WWII. It was a follow-up to a production he had staged during WWI in 1917.

This Is the Army premiered on Broadway in 1942, featuring a cast of 300—enlisted men who could sing and dance. The show then toured the U.S. before traveling to military bases worldwide, running until October 1945.

Berlin originally planned to open the show with a minstrel number, as he had in 1917, but director Ezra Stone pushed back. “Mr. Berlin,” he said, “I know the heritage of the minstrel show. Those days are gone. People don’t do that anymore.” Berlin eventually agreed to cut blackface from the stage production, though the number remained in the 1943 film adaptation.

Yet Berlin also made a bold move for the era: he insisted on integrating the show. At a time when the U.S. military remained segregated, This Is the Army became the only integrated unit in uniform. He even wrote a song specifically for Black performers.

Not all of Berlin’s decisions were as progressive. During the tour, he stunned cast members by complaining that there were “too many Jews in the show and too many of Ezra Stone’s friends.” The remark shocked those present—was the son of a cantor really saying this? For the soldier-performers, the fear was immediate: any cuts to the cast meant reassignment to the front lines.

The show’s use of drag also drew criticism. Warner Brothers, which produced the film version, worried that the female impersonators would limit its international release. “Female impersonators do not exist in Latin America,” claimed one misinformed studio memo. The studio also feared that images of U.S. soldiers in dresses would become enemy propaganda. In response, the film drastically reduced the female impersonators’ roles.

On June 4, 1944, Allied troops took Rome. Just six days behind them, This Is the Army rolled into the city on trucks. Later that month, the company took up residence at the Royal Opera House, performing twice daily.

The show was a global phenomenon, raising millions for the Army Emergency Relief Fund and leaving a lasting legacy.

Playbill from This Is the Army

The playbook is from Flo’s WWII album

Ch. 18: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/03/31/in-the-tent-city-near-pozzuoli-italy/

My Regular Pagan Holiday post

She is a towering figure, casting mountains by flinging stones from her wicker basket. She is the crone goddess, ancient and wise, with flowing white hair and—some legends say—one eye in the center of her forehead. The Cailleach (pronounced kallyak), the Celtic goddess of winter, seizes control of the earth on November 1, at the pagan festival of Samhain (pronounced sow-in), and reigns until the thaw of spring. She governs the weather, especially storms, and with each step, she shapes the land.

The hag’s face is pale blue, cold like a corpse, her long white hair streaked with frost. Cloaked in a gray plaid, she appears worn by time, yet her power is immense. She is both creator and destroyer, molding the hills and valleys with her hammer, a deity tied to cycles of death and rebirth. Some say she has roots as ancient as the Indian goddess Kali.

As the harbinger of winter, the Cailleach has been feared and revered for centuries. On Imbolc, February 1, she is said to gather firewood for the remainder of winter. If the weather is clear and bright, it’s a sign she intends for the cold to stretch on, collecting plenty of wood to sustain her. But if the day is foul, people sigh in relief—the Cailleach sleeps, and winter’s end is near. Today, we mark this custom with Groundhog Day.

“Winter is coming”—a phrase popularized by Game of Thrones—is not just a warning of seasonal change, but a metaphor for scarcity, hardship, and the potential for conflict. The ominous truth is that winter is always coming, unless we are already in the thick of it. Perhaps, politically, we are.

The looming threat of a Trump presidency feels like the onset of a long, harsh winter. It keeps me awake at night. For decades, Republicons have skewed the game, and I’ve lived long enough to witness it firsthand. From voter suppression to outright vote theft, it’s been an ongoing battle. I was blown away by Greg Palast’s latest documentary, Vigilantes Inc.: America’s New Vote Suppression Hitmen, produced by Martin Sheen, George DiCaprio, and Maria Florio (Oscar, Best Documentary). He exposes the political history of racist Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp and his slave owning family. Stream it for free.

For those unfamiliar with Greg Palast, he’s a freelance journalist with a history of working for the BBC and The Guardian. His investigations predict that MAGA extremists may riot on December 11, the constitutional deadline for states to submit their final lists of electors. You can read more on his site: https://www.gregpalast.com/maga-militants-to-riot-on-december-11/

I’m sending this message before Samhain, hoping these warnings help to thwart the political winter ahead. We may already be in the storm’s grip, but awareness can help us weather it.

For those of you in Sonoma County, I hope you’ll join me at a Democracy Fair, sponsored by the Deep Democracy group of the North Bay Organizing Project. Get voter information about local and state propositions and races. Plus games and prizes! It’s happening this Friday October 18 from 4 to 7pm at the SRJC student center. Registering ahead will help us plan. Here’s the RSVP link: tinyurl.com/deepdemfair. (Apologies to those I’ve already sent this to.)

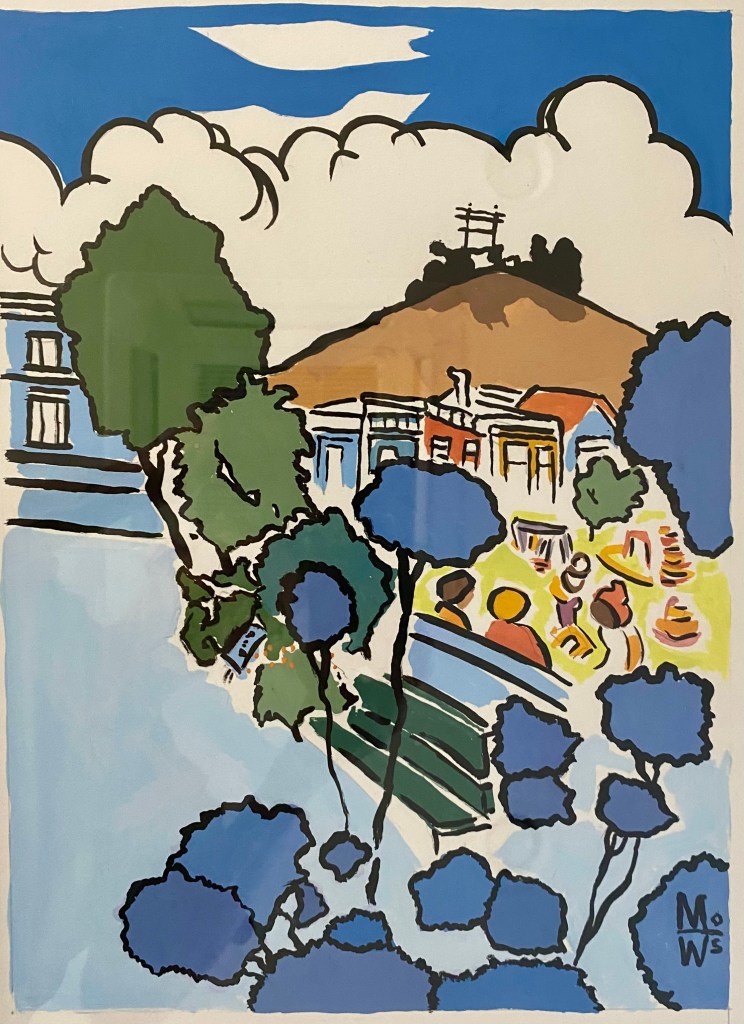

One more thing. I was saddened to learn of the death of my friend, the artist and writer Mary Wings in San Francisco. We were both born in 1949 (it was a very good year for Boomers) and shared a neighborhood in Bernal Heights. Mary was kind of famous; she rated an obit in the New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/08/arts/mary-wings-dead.html?unlocked_article_code=1.SU4.GC0y.GZ_rimClOb6P&smid=url-share

She was always working on art projects and her friends were often the lucky recipients of her creations. One of her gifts to me was this painting of Bernal Hill viewed from Precita Park where she lived. I lived on the opposite side of the hill. The painting had originally been framed in something she’d found at Scrap, but it fell apart over time. Recently, I rediscovered it in the garage and had it reframed. Now it’s hanging on the kitchen wall, and it’s a beautiful way to remember both Mary and our beloved San Francisco neighborhood.

Sending Samhain greetings to all.

Love, Molly (and Holly)

The top photo is by David Mirlea on Unsplash (having trouble with captions)

Black, Lesbian, or Just a Woman?

Tradeswomen Respond to Workplace Violence

Carpenter apprentice Outi Hicks was working on a job in Fresno, California in 2017 when she encountered continuing harassment from another worker there. She didn’t complain and no one stood up for her. Then her harasser attacked her and beat her to death.

We don’t know whether Outi (pronounced Ootee) was murdered because she was Black, lesbian or just female. But we do know that being all three put her at greater risk. Outi was 32 and a mother of three.

In response, tradeswomen organized Sisters Against Workplace Violence and worked with the Ironworkers Union (IW) to launch a program called Be That One Guy. The program’s aim is to “turn bystanders into upstanders.” Participants learn how to defuse hostile situations and gain the confidence to be able to react when they see harassment.

“Outi Hicks’ murder hit me hard,” says Vicki O’ Leary, the international IW general organizer for safety and diversity. “Companies and unions need to change the focus of their harassment policies and need to get tougher with harassers.”

Often the victim of harassment is moved to a different crew or jobsite in an effort to defuse the situation. But such a response actually punishes the victim and not the aggressor, who remains unaffected and may continue to harass other workers.

O’Leary says one of the most important parts of the program is when participants take the pledge:

“It only takes one guy to talk to the harasser or to file a complaint with the crew boss. It’s even better when the whole crew stands up together to end harassment, and we are now seeing this happen on job sites around the country,” says O’Leary. She tells of an apprentice who was being harassed by a supervisor. Seeing the harassment, everyone on the crew began to treat the supervisor the same way he was treating the apprentice. His behavior changed in a day.

The IW is rolling out the program through their district councils. They want to share it with other unions and, says O’Leary, they’re hoping general contractors will jump on.

Another anti-violence program started by tradeswomen and our allies also is specifically tailored to the construction industry.

ANEW, the pre-apprenticeship training program in Seattle, created its program, RISE Up, to counter the number of people, and especially women, who leave the construction trades because of a hostile work environment. ANEW director, Karen Dove, developed the program after meetings with contractors who would say “women just need tougher skin.”

The program focuses on empowering workers and employers to prevent and respond to workplace violence. It offers a range of services, including training sessions, risk assessments, and support for workers who have experienced violence.

Training sessions are designed to help workers and employers identify the warning signs of workplace violence and take proactive steps to prevent it. The training covers conflict resolution, de-escalation techniques, and the importance of creating a positive work environment.

The program is concerned with psychological well being and is now working with a union to develop mental health services for Black workers.

RISE Up also offers risk assessments to construction companies, which help them identify areas of their workplace that may be at higher risk of violence.

Marquia Wooten, director of RISE Up, says the program is designed to change the culture of construction. Wooten worked in the trades for ten years as a laborer and an operating engineer. “When I was an apprentice they yelled and screamed at me,” she says. She notes that men suffer from harassment too. “The suicide rate of construction workers is number two after vets and first responders,” she said. “Substance abuse is high in construction.”

ANEW partners with cities, public entities, unions, schools and employers. “They do want change in the industry,” says Wooten. Less workplace violence is good for the bottom line.

But training workers is not enough. Union staff needs training in how to respond to harassment as well. Liz Skidmore recently retired as business representative/organizer at North Atlantic States Regional Council of Carpenters. They created a training to help union staff members know what to do when a member complains.

“New federal regulations require that every person on the construction job who comes into contact with apprentices go through anti-harassment and discrimination training,” says Skidmore.

“Most of corporate America requires annual training about sexual harassment, but most trainers don’t know the blue collar world,” she says. Trainers can be classist. “To be effective, the trainer has to like these guys.”

While tradeswomen have long been virtually invisible on the front lines of the Feminist and Civil Rights Movements, we still are the ones who daily confront the most aggressive kind of sexism and racism in our traditionally male jobs. For going on five decades now we have been devising strategies to counter isolation and harassment at work and to increase the numbers of women in the union construction trades. Now we are working to educate the construction industry about how to end workplace violence. Women in construction are still isolated and often the only woman on the job. We need our brothers to act as allies.

As with women in construction, queer and transgender folks must depend on allies to stand up to bullies. We can’t do this by ourselves. The anti-violence programs developed by tradeswomen are programs that we queers can adapt to protect our communities.

Sometimes you just have to say something.

Postscript 2025: Another sister has been murdered on the job by a coworker. Minneapolis. He killed her with a sledge hammer. Story on 19th: https://19thnews.org/2025/11/amber-czech-welder-murder-tradeswomen-demand-action/

The Black Freedom Movement and Tradeswomen History

I want to take us back in time and imagine a world, a culture, in which job categories were firmly divided between MEN and WOMEN. Women were restricted to pink collar jobs that paid too little to raise a family on or even to live without a man’s support. Even doing the same jobs, women were legally paid less than men. Married women were not allowed to work outside the home. Single women who found jobs as teachers or secretaries were fired as soon as they married. Black people were only allowed to work as laborers or house cleaners.

This was the world we fought to change.

Tradeswomen who have jobs today must thank Black workers who began the fight for jobs and justice.

The Black Freedom Movement has advocated for workplace equity since the end of the Civil War.

The movement gained power during and after WWII. A. Philip Randolph headed the sleeping car porters union, the leading Black trade union in the US. In 1940 he threatened to march on Washington with ten thousand demonstrators if the government did not act to end job discrimination in federal war contracts. FDR capitulated and signed executive order 8802, the first presidential order to benefit Blacks since reconstruction. It outlawed discrimination by companies and unions engaged in war work on government contracts. This executive order marked the start of affirmative action.

The fight to desegregate the workforce continued.

In the early 1960s in the San Francisco Bay Area, protesters organized successful picket campaigns against businesses that refused to hire Blacks, including the Palace hotel, car dealerships and Mel’s Drive-In. Many of the protesters were white students at UC Berkeley.

In August 1963, the march on Washington brought 200,000 people to the capitol to protest racial discrimination and show support for civil rights legislation. The civil rights act of 1964, signed into law by President Johnson, is the legal structure that women and POC have used to put nondiscrimination into practice.

But change did not come quickly or easily.

Black workers at a tire plant in Natchez Mississippi were organizing to desegregate jobs. The CIO, Congress of Industrial Organizations, supported them in this fight. In 1967, three years after the civil rights act became law, a Black man, Wharlest Jackson, who had won a promotion to a previously “white” job in the tire plant, was murdered by the KKK. They blew up his truck as he was driving home from work. No one was ever arrested or prosecuted for this crime.

Wharlest Jackson was the father of five. His wife, Exerlina, was among those arrested for peacefully insisting on equal treatment during a boycott of the town of Natchez’s white businesses. She was sent to Parchman penitentiary.

Jackson was just one of many who died for our right to be treated equally at work.

Tradeswomen are part of the feminist, civil rights and union movements. We continue to seek allies because we are few.

Discrimination has not ended, but, because of decades of organizing, our work lives have improved. We owe much to the Black workers who sought equity in employment for decades before us.

Photo: the Zinn Education Project