My Regular Pagan Holiday Post

Summer (and Winter) Solstice will be June 20, 2025

For years, these pagan holiday letters have followed the rhythm of the Northern Hemisphere. So it’s about time we turned our gaze south. What is the summer solstice for us in the north is, of course, the winter solstice down under.

In Aotearoa (the Māori name for New Zealand, often translated as “Land of the Long White Cloud”), the winter solstice is marked by Matariki, a celebration that signals the Māori New Year. In 2022, Matariki was officially recognized as New Zealand’s first indigenous national holiday — a milestone in honoring the traditions of the land’s first people.

Rooted in ancient Māori astronomy and storytelling, Matariki revolves around the reappearance of a small but powerful star cluster in the early morning sky — known in Māori as Matariki, and in Western astronomy as the Pleiades or the Seven Sisters. Its rising marks a time of renewal, remembrance, and reconnection — with ancestors, the earth, and each other.

The date of Matariki shifts slightly each year, determined by both the lunar calendar and careful observation of the stars. Māori astronomers and iwi (tribal) experts consult mātauranga Māori — traditional Māori knowledge systems — to ensure the timing reflects ancestral wisdom. In precolonial times, the clarity and brightness of each star helped forecast the year’s weather, harvest, and overall wellbeing.

Unlike the linear passage of time in the Gregorian calendar, Māori time is circular — woven from moon phases, tides, seasons, and stars. Matariki is not just a new year, but a return point. A moment to pause, reflect on what has been, and plan how to move forward in harmony with the natural world.

At the heart of Matariki is kaitiakitanga — the ethic of guardianship. It’s the understanding that humans are not owners of the earth, but caretakers. We are part of the land, sea, and sky, and we carry the responsibility to protect and sustain them.

When Matariki rises just before dawn, it opens a space for both grief and celebration: to mourn those who’ve passed, give thanks for what we have, and set intentions for the year ahead. It reminds us of the interconnectedness of whānau(family), whakapapa (genealogy), and whenua (land).

The name Matariki is often translated as “the eyes of the chief,” from mata (eyes) and ariki (chief). According to one well-known Māori legend, the stars are the eyes of Tāwhirimātea, the god of winds and weather. In grief over the separation of his parents — Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (Earth Mother) — Tāwhirimātea tore out his own eyes and cast them into the heavens.

In a world that often values speed over stillness, Matariki offers a different rhythm. It’s a celestial breath — a reminder that time moves in cycles. That rest and reflection are just as important as action. That the sky still holds stories if we remember to look up.

The 9 Stars of Matariki

Each star in the Matariki cluster has its own role and significance:

- Matariki – Health and wellbeing

- Tupuānuku – Food from the earth

- Tupuārangi – Food from the sky (birds, fruits)

- Waitī – Freshwater and the life within it

- Waitā – The ocean and saltwater life

- Waipuna-ā-Rangi – Rain and weather patterns

- Ururangi – Winds and the atmosphere

- Pōhutukawa – Remembrance of those who have passed

- Hiwa-i-te-Rangi – Aspirations, goals, and wishes for the future

For Māori, these stars are not just celestial objects — they are guardians. They watch over the land, sea, and sky, and in doing so, remind us of our responsibility to them.

As global conversations about climate change and sustainability grow more urgent, the values of Matariki — care, reverence, reflection, and renewal — feel especially resonant. It’s a time to return to what matters, to honor the past, and to move forward in a way that honors both our roots and our shared future on this earth.

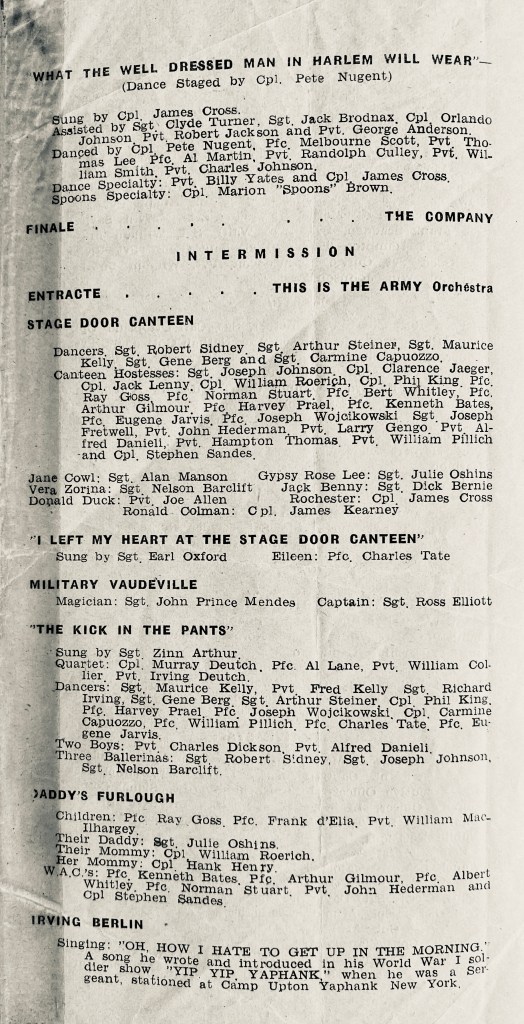

North Bay Rising

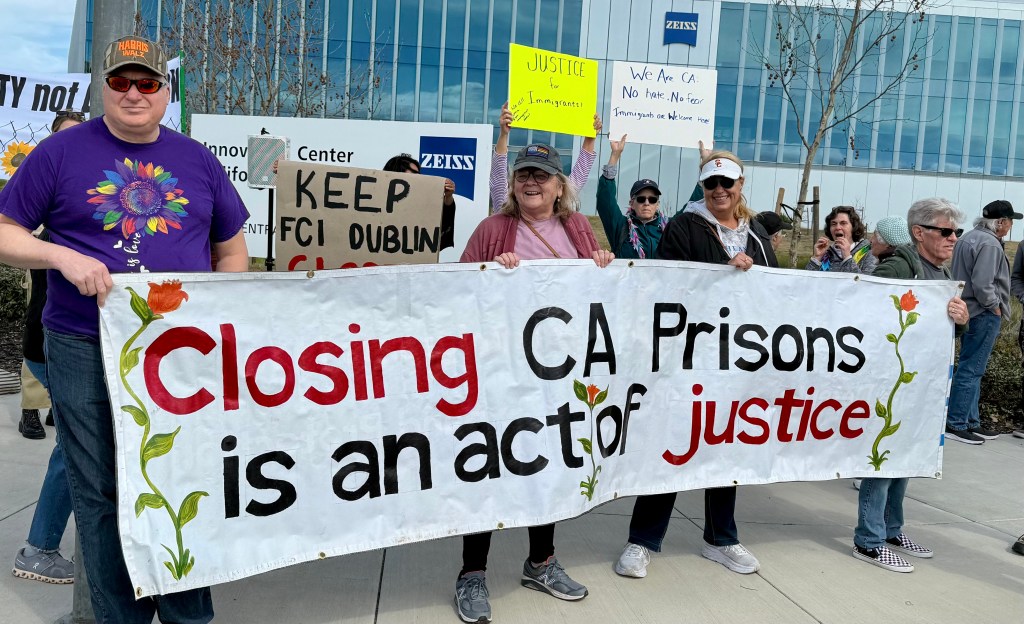

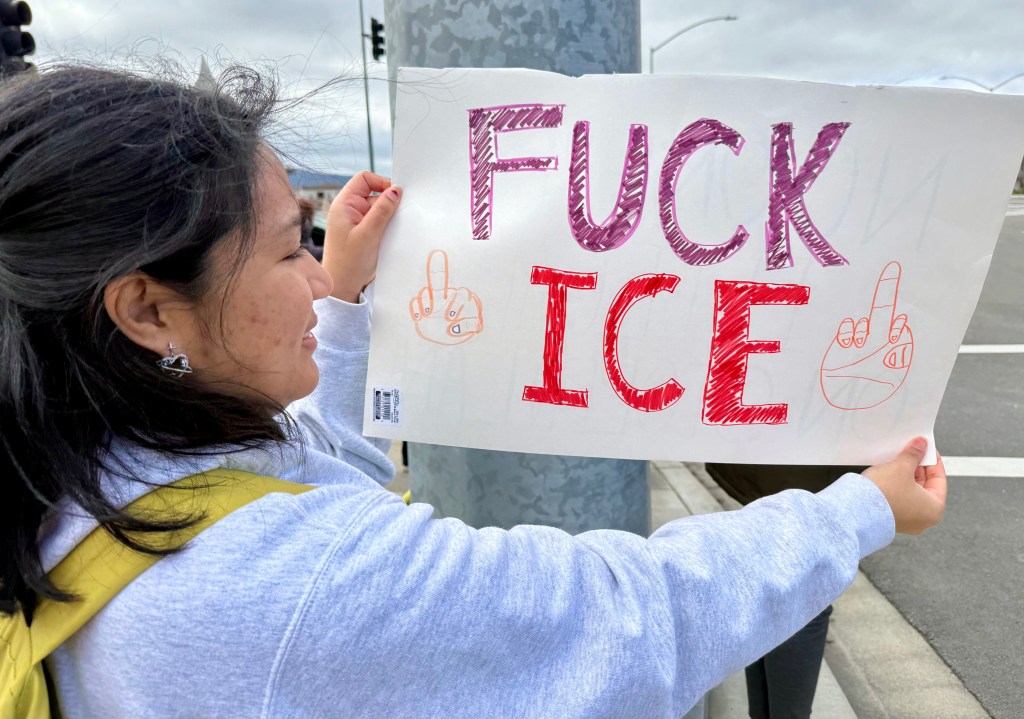

In Santa Rosa and across the North Bay, we’re mad as hell—and we’ve taken to the streets. From the Hands Off! protest in April that brought 5,000 people to downtown Santa Rosa, to thousands more mobilizing in surrounding towns, resistance to the rise of fascism in the U.S. is fierce and growing.

Some of the signs from our protests

Here in Sonoma County, protests are a near-daily occurrence. Demonstrators are targeting a wide range of issues: U.S. complicity in the genocide of Palestinians, Avelo Airline’s role in deportation flights, Elon Musk’s attacks on federal institutions like Social Security and Medicare/Medicaid, the gutting of the Veterans Administration, the criminalization of immigrants, assaults on free speech, and—by us tradeswomen—the dismantling of affirmative action and DEI initiatives.

The Palestinian community and its allies have been gathering every Sunday at the Santa Rosa town square since October 2023.

Weekly actions include:

- Thursdays: We the People protest in Petaluma.

- Fridays: Veteran-focused rallies protesting VA budget cuts.

- Fridays/Saturdays: Petalumans Saving Democracy actions.

- Saturdays: Tesla Takedown at the Santa Rosa showroom, and a vigil for Palestine in Petaluma.

- Sundays: Protest at the Santa Rosa Airport against Avelo Airlines, and a Stand with Palestine demonstration in town.

- Tuesdays: Resist and Reform in Sebastopol.

- Ongoing: In Cotati, a weekly Resist Fascism picket line.

In Sonoma Plaza, there’s a weekly vigil to resist Trump. Sebastopol hosts a Gaza solidarity vigil, along with Sitting for Survival, an environmental justice action.

Beyond the regular schedule, spontaneous and planned actions continue:

- A march to raise awareness of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

- In Windsor, women-led organizing for immigrant rights.

- A multi-faith rally at the town square on April 16.

- Protest musicians and singers are coming together to strengthen the movement with art.

Trump’s goons are jailing citizens, and fear runs deep, especially among the undocumented and documented Latinx population—who make up roughly a third of Santa Rosa. But fear hasn’t silenced them. They continue to show up and speak out.

I’ve joined the North Bay Rapid Response Network, which mobilizes to defend our immigrant neighbors from ICE raids.

Meanwhile, our school systems are in crisis. Sonoma State University is slashing classes and programs in the name of austerity. Students and faculty are fighting back with protests, including a Gaza sit-in that nearly resulted in a breakthrough agreement with the administration.

Between all this, Holly and I made it to the Santa Rosa Rose Parade. The high school bands looked and sounded great—spirited and proud. Then, our Gay Day here on May 31, while clouded by conflict about participation by cops, still celebrated us queers.

And soon, I’ll hit the road heading to Yellowstone with a friend. On June 14, we’ll join protesting park rangers in Jackson, Wyoming as part of the No Kings! national day of action—a protest coordinated by Indivisible and partners taking place in hundreds of cities across the country.

On the Solstice, June 20 in the Northern Hemisphere, we expect to be in Winnemucca, Nevada, on the way home.

Happy Solstice to all—Winter and Summer!

Photo of the Pleiades: Digitized Sky Survey