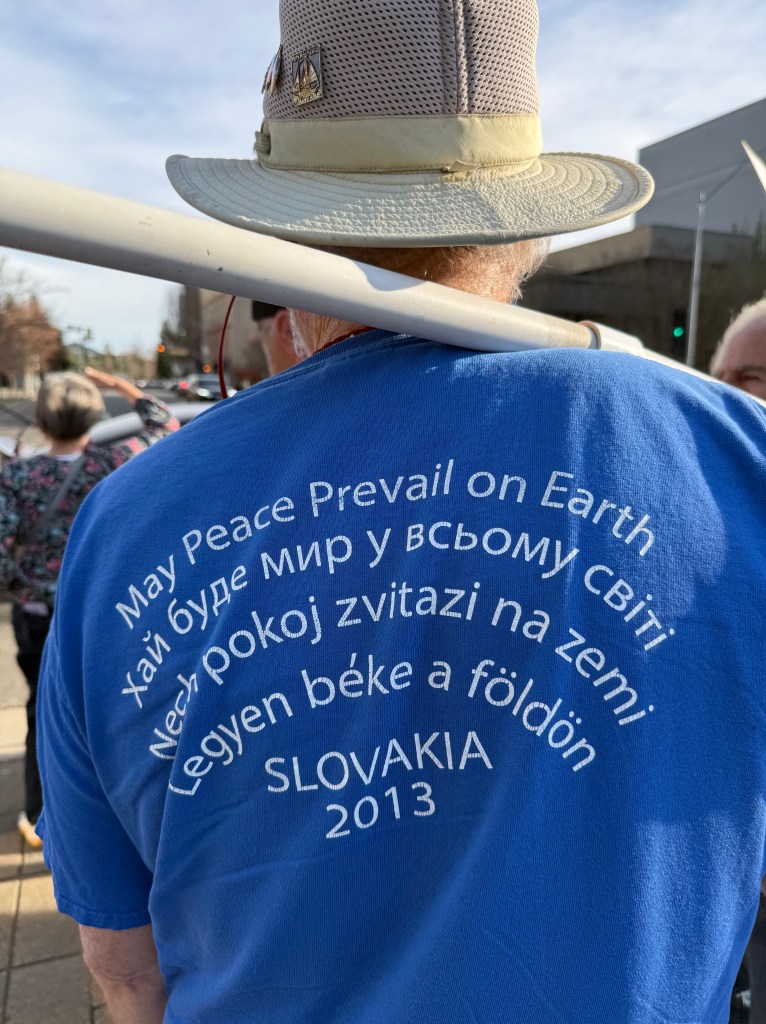

Protest March 7, 2026 Santa Rosa

Flo’s fiancé Gene is killed in action

My Mother and Audie Murphy Ch. 42

I’m finding it so very difficult to tell this story. Thinking about war all the time takes a toll on the psyche.

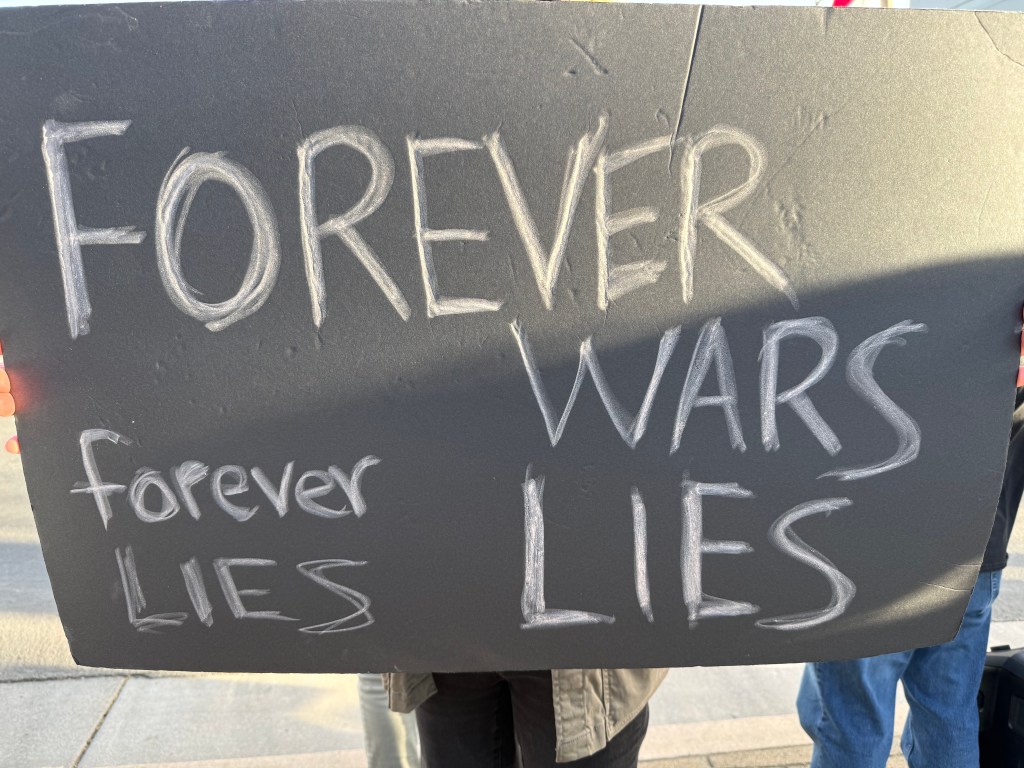

This morning, before sitting down to write, I went to a protest at the local veterans clinic. We were there to demand an end to cuts to the Veterans Administration. Many of the protesters—like the woman who organized it—are vets themselves. There’s always music at these gatherings: sometimes a live band called Good Trouble, sometimes just a boombox. I usually love to dance, to sing along. But lately, the old anti-war songs catch in my throat.

I’m gonna lay down my sword and shield,

Down by the riverside.

I ain’t gonna study war no more.

War! What is it good for? Absolutely nothing.

John Lennon singing Give Peace a Chance.

They all make me cry now, and when you’re crying, it’s hard to sing. We’ve been singing these songs for so damn long. All my adult life, since I was a college student protesting the Vietnam War in the 1960s. Flo protested with me. She was a patriot, but her time in Europe changed her. The war turned her against war.

Flo’s Diary Tells the Story

Flo and her crew had just returned from a brief trip to Paris before getting back to work, serving donuts in remote villages. Still hoping to see her fiancé Gene, Flo went to the Third Battalion headquarters. There, a major gave her the news: Gene had been killed by a mortar shell.

“Dear God!” she wrote in her diary.

Those were among the last words she wrote in it. Except for a few brief notes, the rest of her wartime diary is blank. From here on, I have only the letters she saved, and newspaper clippings pasted into her album, to help me tell the rest of her story.

My grandmother, Gerda, saved the letter Flo wrote to her.

Sun. nite Oct. 29

Dearest Mom–

I need you so! I just learned that Gene was killed yesterday at the front–in fact, I was at his battalion headquarters, a short distance back, this afternoon and the major broke the news to me. I can’t believe it; I just saw him a few days ago–before we left for Paris–and everything seemed wonderful. He was hit by a mortar shell and died very quickly. Oh, Mom, I loved him so much–he was so wonderful to me–and so attractive and fine. He was his mother’s favorite and the family “mainstay”–it will break her heart–and mine too. Right now I want to come home and see you–that would help. I had so much faith that this time, things would work out and I am so sure he was the “right” person. I’ve prayed for him and his safety, but war is such an evil thing, prayers don’t help much, I’m afraid.

I’m trying very hard to believe in all the things you taught me, but it certainly is hard. Perhaps now I realize, a little, how you felt when Daddy died, though it isn’t quite the same. Gene had sent home for rings for me and wanted so much to get married and have children–like all these men over here who are fighting and dying every day.

I wish there were a church to go to around here–it would help me, I think. Funny how that is what you need when these things happen. Everything is blank and black ahead right now and the shock has been terrific. Of course it will wear off and I will accept it, but it is very, very hard. I didn’t realize how much he meant until I heard the tragic news, but I am glad we had so many good times and that I made him happy for a few months. You would have loved him, Mom; he was so big and handsome and good to everyone. His boys are heartbroken–the whole battalion was shocked. I have so many friends among the 36th engineers and they are wonderful to me. It doesn’t bring Gene back, tho, and I can’t feel much of anything.

I may go up and see Eve again for a few days; it will help to see her–she was so nice to us girls when we were there.

Am glad you finally got my letters, Mom; it was worrying me that you didn’t hear, but mail service has been perfectly terrible. I hope they all catch up with you soon. Can’t write anymore right now. I’ll try to be brave. Pray for me, Mom.

Love, Florence

Mon. A.M. Forgot to tell you in the excitement that I ran into Janet Tyson in Paris! She drove back with us and we took her to her husband’s camp–his division is right with ours. She dropped by this morning and talked me into going back to Paris for a few days to be with her and Eve. I don’t know what is best, but I’m on my way there and may feel better.

I read the second chapter of Timothy and thought of Gene where it says “I have fought the good fight”–he certainly did! I am trying to draw on those “inner resources” but it is so hard and I shall miss him so much. Write me.

All my love, Florence

Susan Jenson remembered her mother Janet saying, “Flo, like the rest of them, suffered loss. So sad to finally find Gene—only to lose him.”

Ch. 43: https://mollymartin.blog/2025/07/27/black-women-save-the-us-army/

My Regular Pagan Holiday Post

Summer (and Winter) Solstice will be June 20, 2025

For years, these pagan holiday letters have followed the rhythm of the Northern Hemisphere. So it’s about time we turned our gaze south. What is the summer solstice for us in the north is, of course, the winter solstice down under.

In Aotearoa (the Māori name for New Zealand, often translated as “Land of the Long White Cloud”), the winter solstice is marked by Matariki, a celebration that signals the Māori New Year. In 2022, Matariki was officially recognized as New Zealand’s first indigenous national holiday — a milestone in honoring the traditions of the land’s first people.

Rooted in ancient Māori astronomy and storytelling, Matariki revolves around the reappearance of a small but powerful star cluster in the early morning sky — known in Māori as Matariki, and in Western astronomy as the Pleiades or the Seven Sisters. Its rising marks a time of renewal, remembrance, and reconnection — with ancestors, the earth, and each other.

The date of Matariki shifts slightly each year, determined by both the lunar calendar and careful observation of the stars. Māori astronomers and iwi (tribal) experts consult mātauranga Māori — traditional Māori knowledge systems — to ensure the timing reflects ancestral wisdom. In precolonial times, the clarity and brightness of each star helped forecast the year’s weather, harvest, and overall wellbeing.

Unlike the linear passage of time in the Gregorian calendar, Māori time is circular — woven from moon phases, tides, seasons, and stars. Matariki is not just a new year, but a return point. A moment to pause, reflect on what has been, and plan how to move forward in harmony with the natural world.

At the heart of Matariki is kaitiakitanga — the ethic of guardianship. It’s the understanding that humans are not owners of the earth, but caretakers. We are part of the land, sea, and sky, and we carry the responsibility to protect and sustain them.

When Matariki rises just before dawn, it opens a space for both grief and celebration: to mourn those who’ve passed, give thanks for what we have, and set intentions for the year ahead. It reminds us of the interconnectedness of whānau(family), whakapapa (genealogy), and whenua (land).

The name Matariki is often translated as “the eyes of the chief,” from mata (eyes) and ariki (chief). According to one well-known Māori legend, the stars are the eyes of Tāwhirimātea, the god of winds and weather. In grief over the separation of his parents — Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (Earth Mother) — Tāwhirimātea tore out his own eyes and cast them into the heavens.

In a world that often values speed over stillness, Matariki offers a different rhythm. It’s a celestial breath — a reminder that time moves in cycles. That rest and reflection are just as important as action. That the sky still holds stories if we remember to look up.

The 9 Stars of Matariki

Each star in the Matariki cluster has its own role and significance:

For Māori, these stars are not just celestial objects — they are guardians. They watch over the land, sea, and sky, and in doing so, remind us of our responsibility to them.

As global conversations about climate change and sustainability grow more urgent, the values of Matariki — care, reverence, reflection, and renewal — feel especially resonant. It’s a time to return to what matters, to honor the past, and to move forward in a way that honors both our roots and our shared future on this earth.

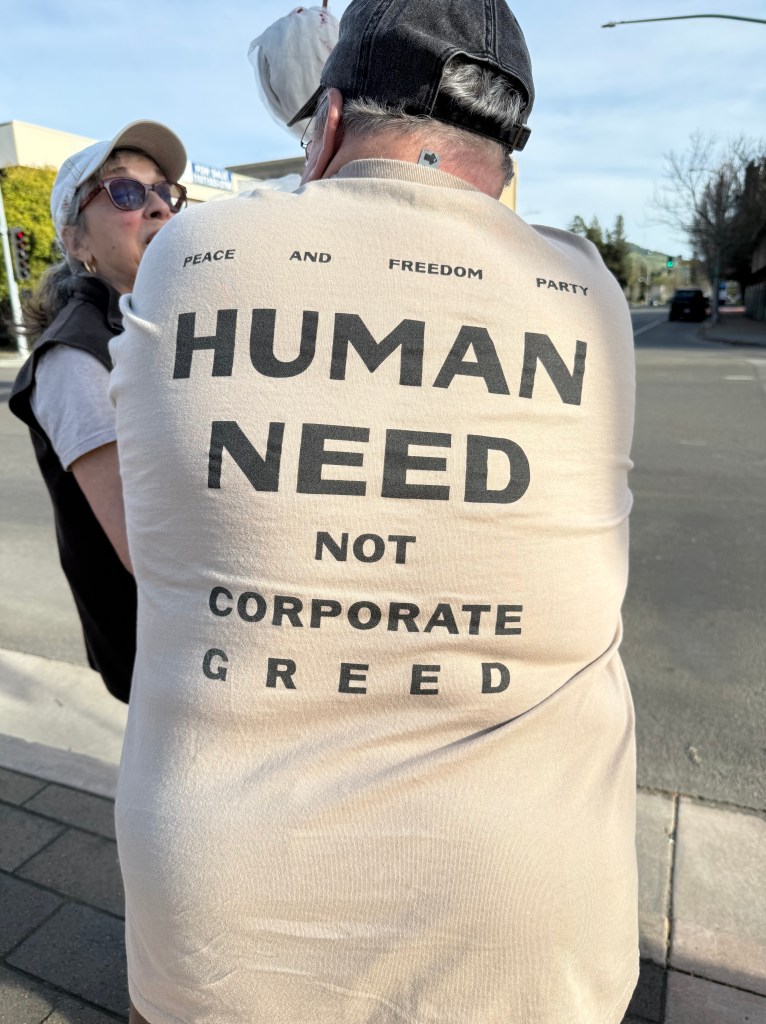

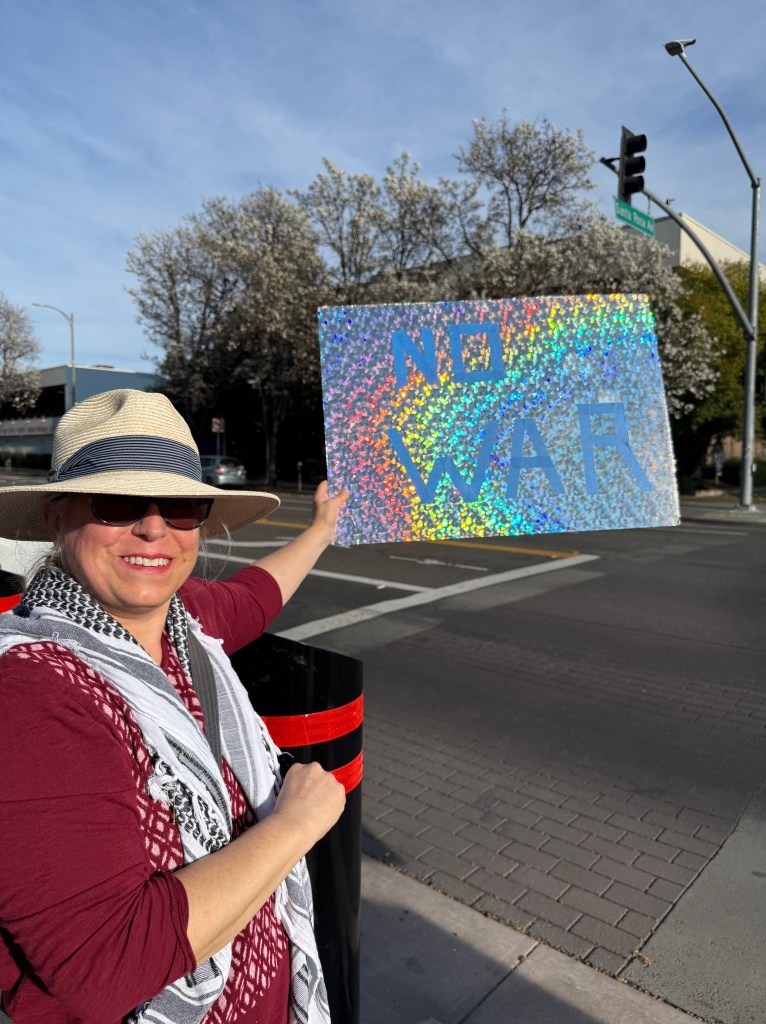

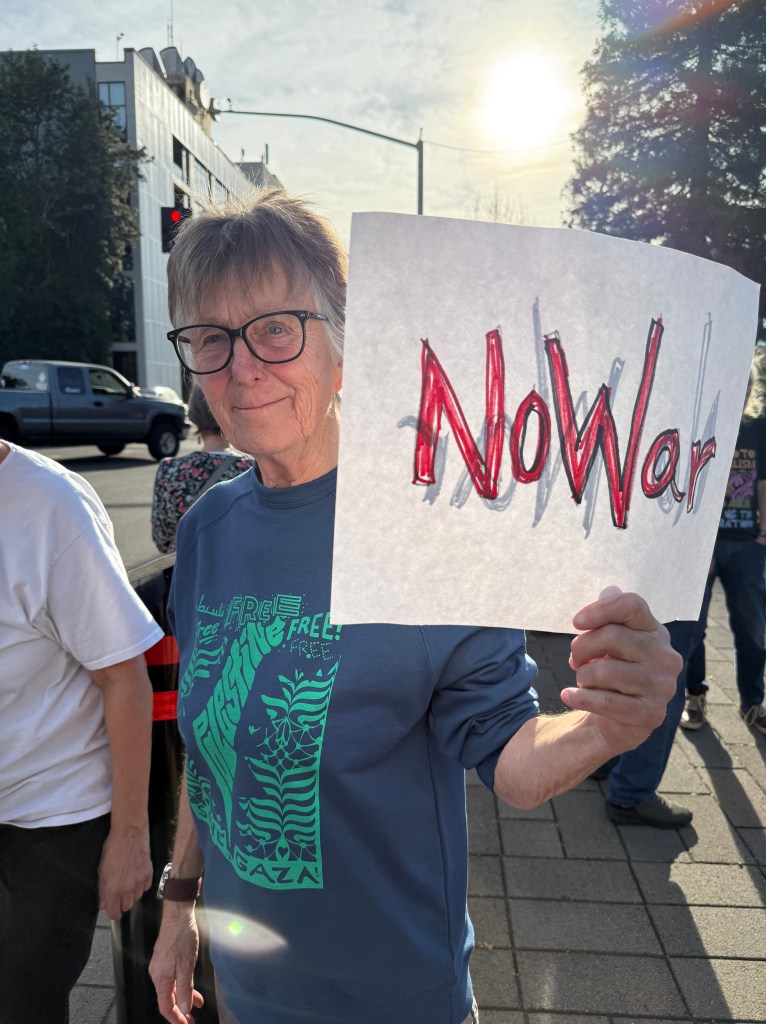

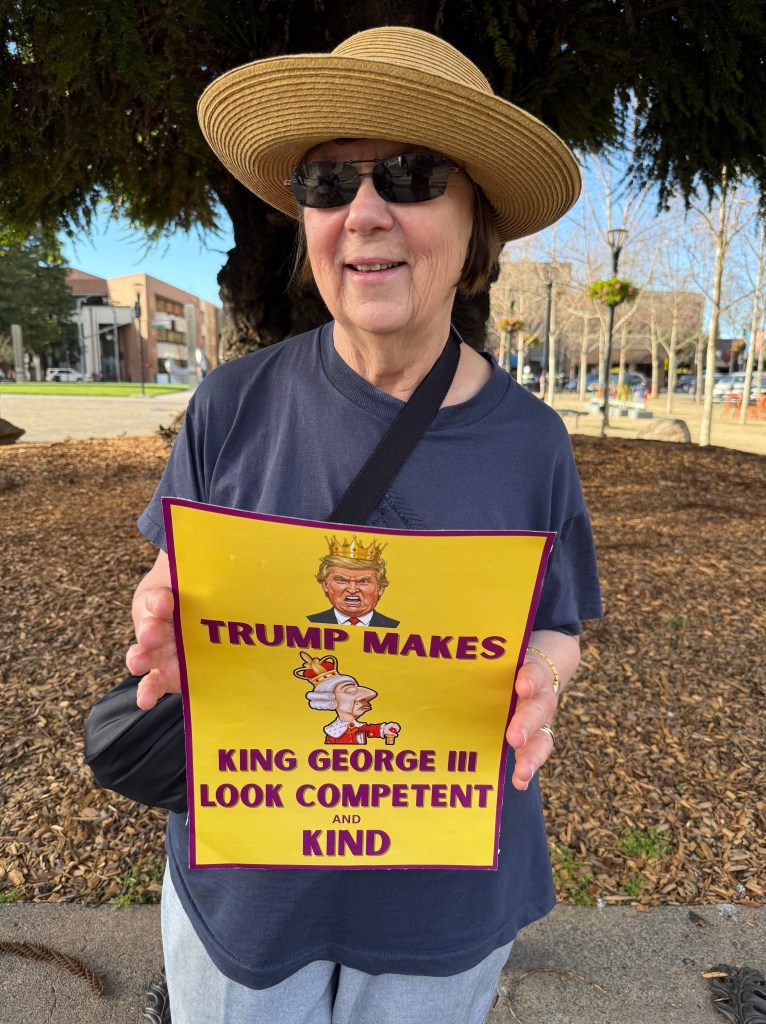

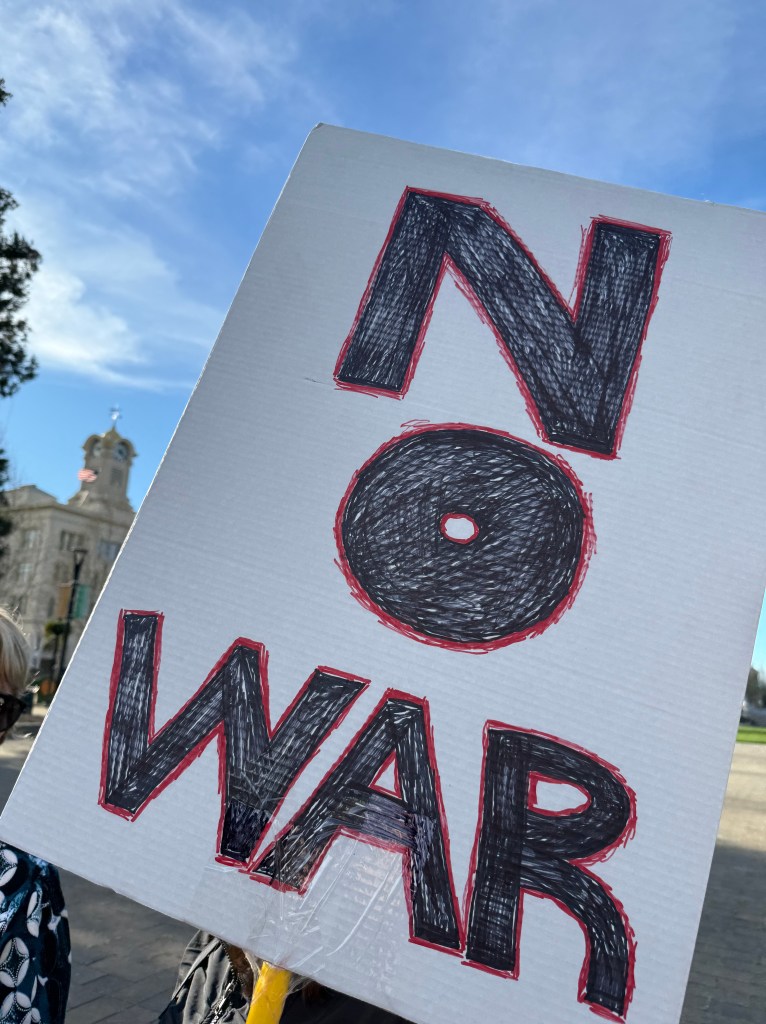

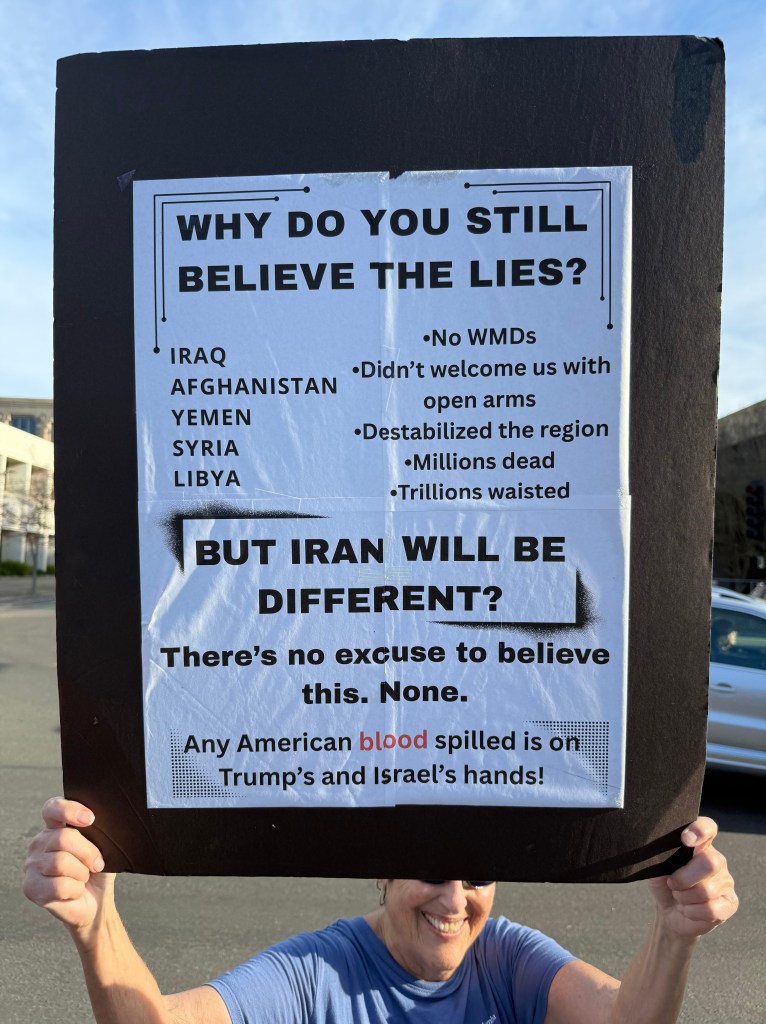

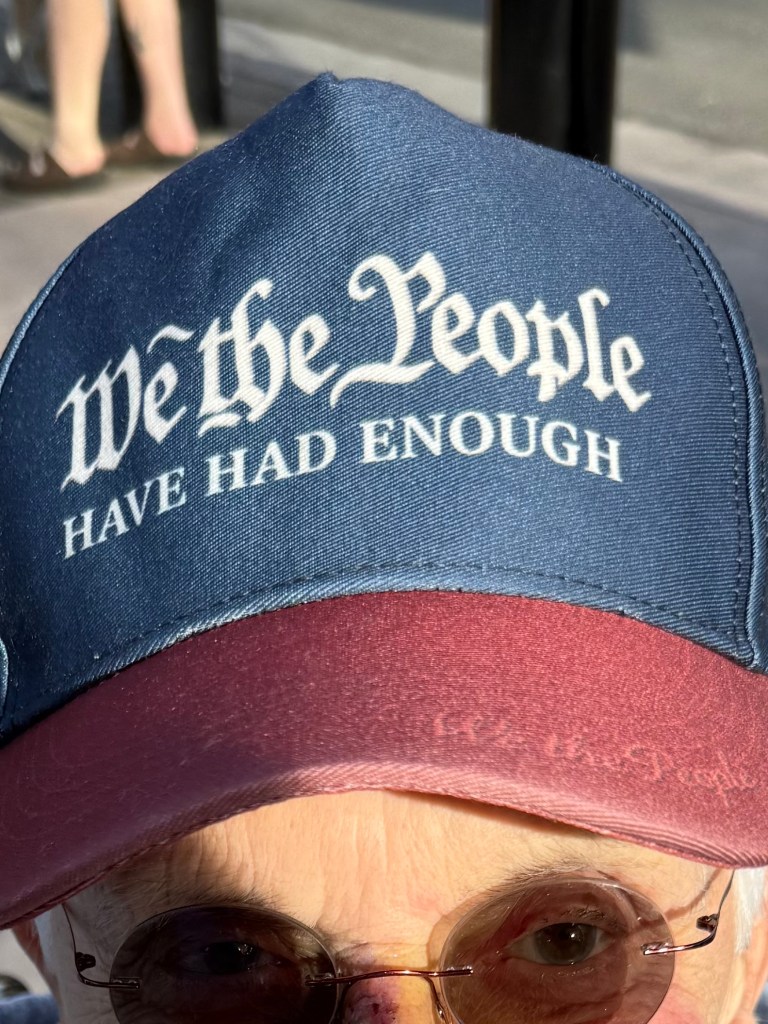

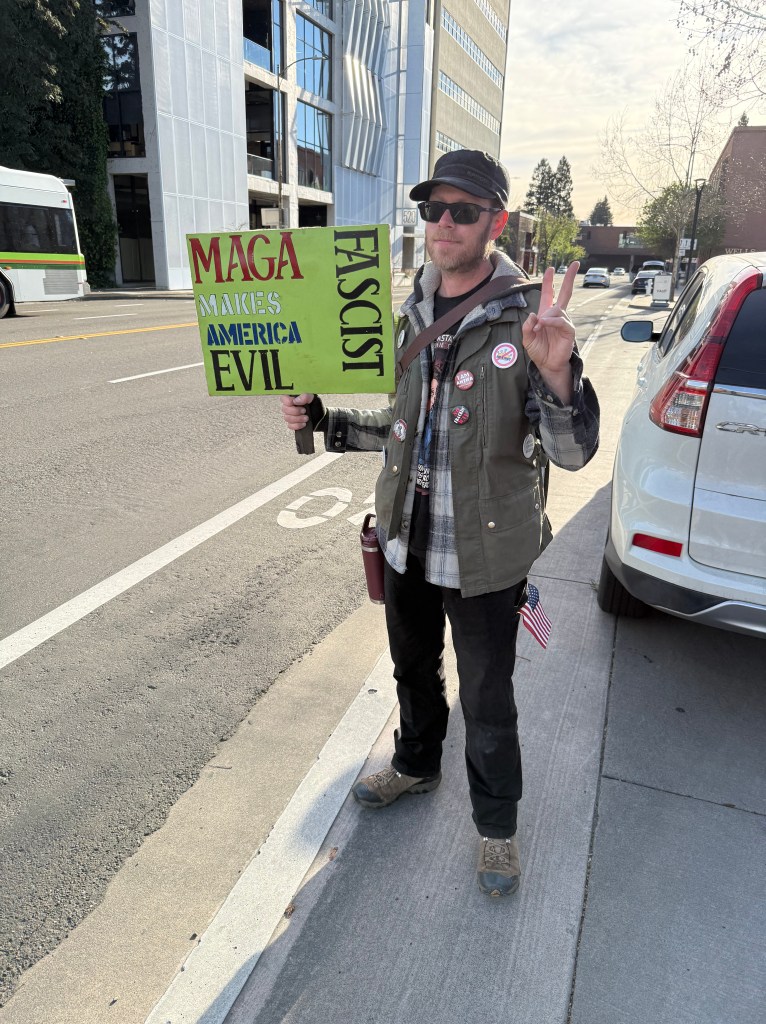

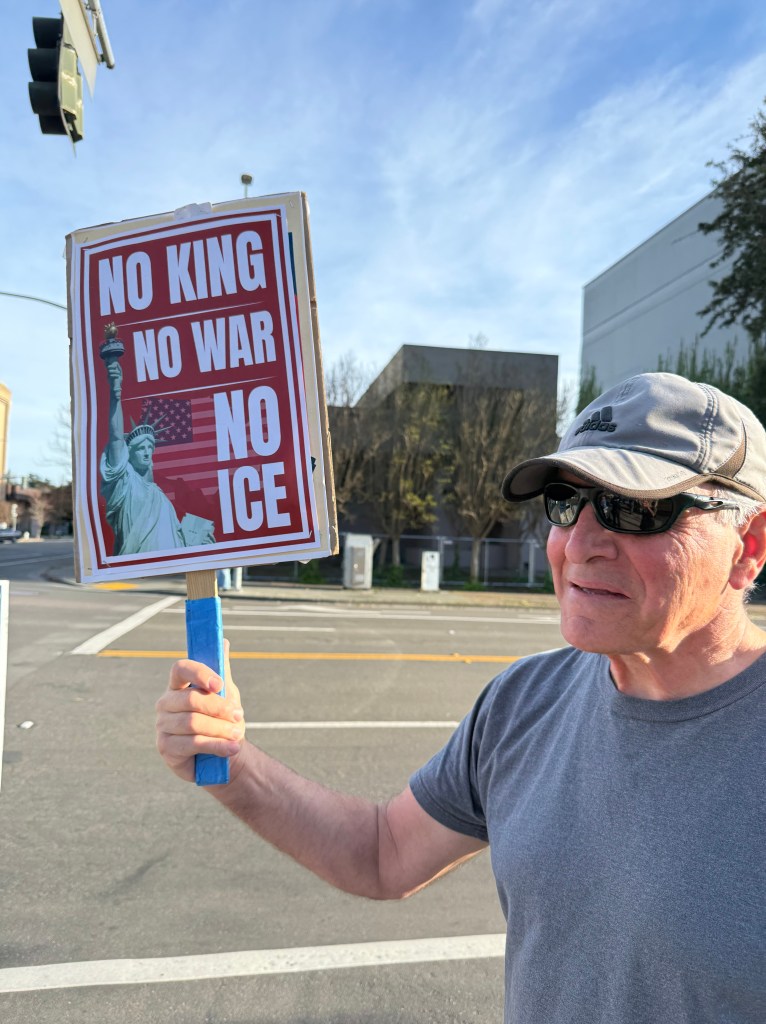

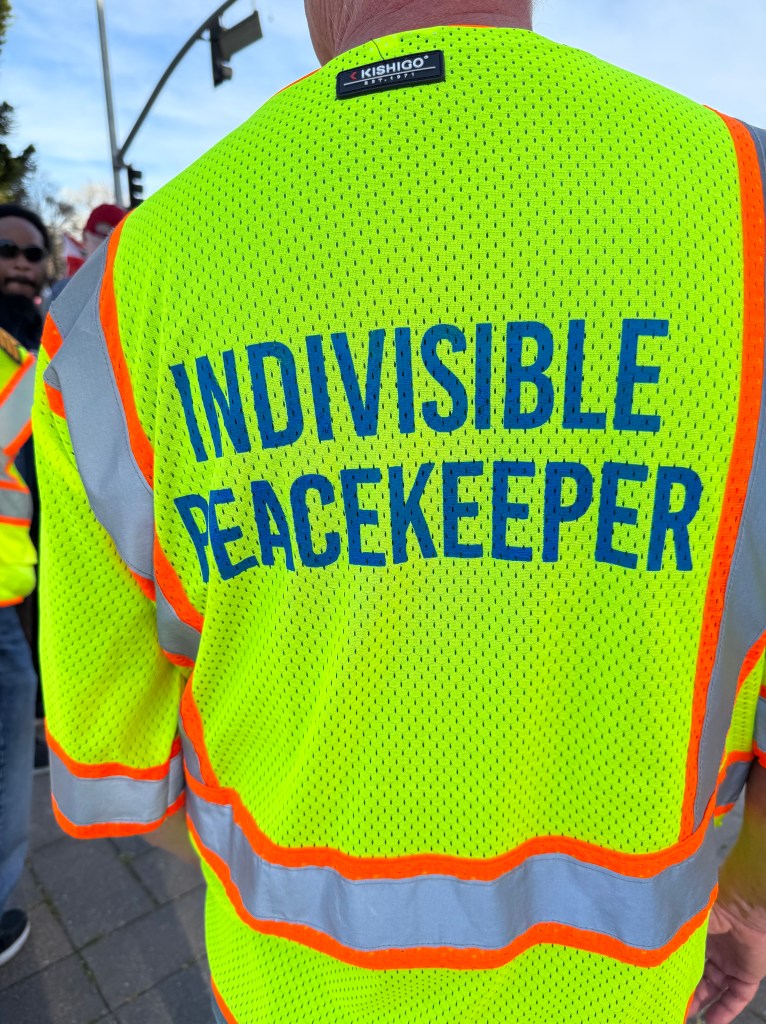

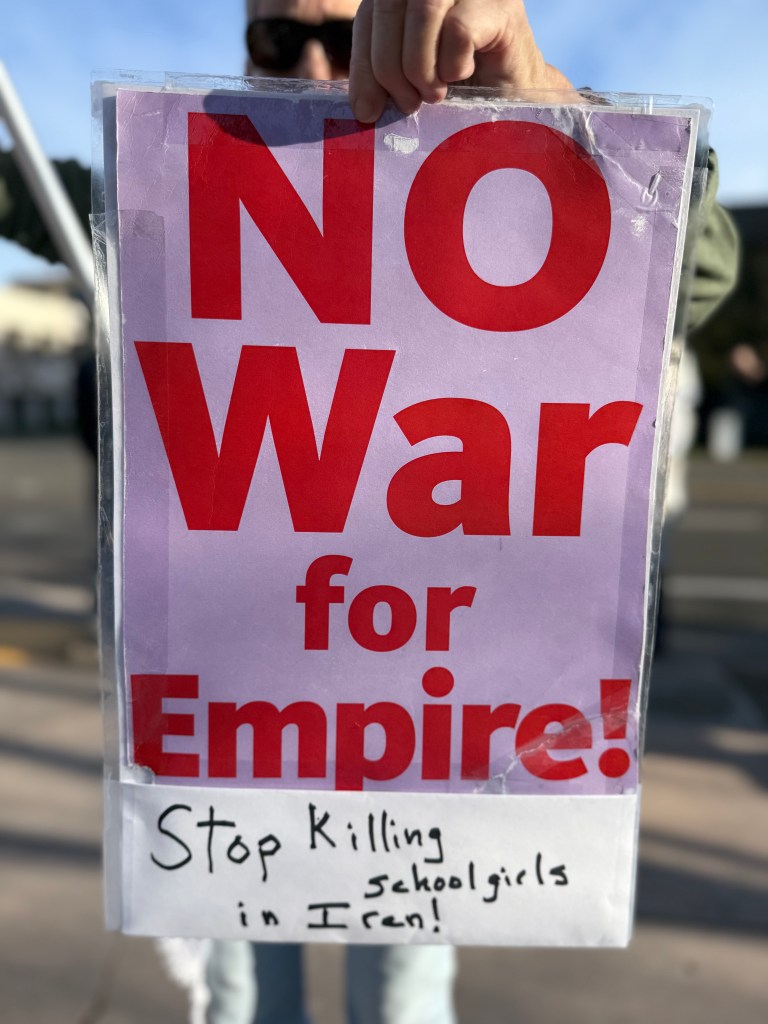

North Bay Rising

In Santa Rosa and across the North Bay, we’re mad as hell—and we’ve taken to the streets. From the Hands Off! protest in April that brought 5,000 people to downtown Santa Rosa, to thousands more mobilizing in surrounding towns, resistance to the rise of fascism in the U.S. is fierce and growing.

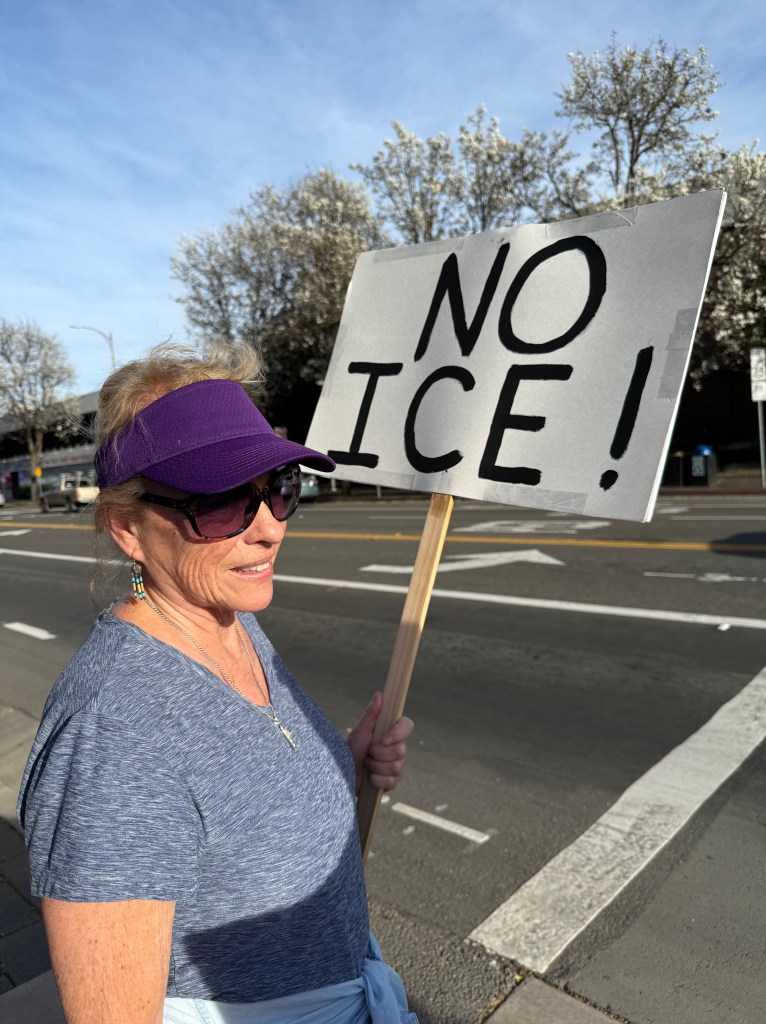

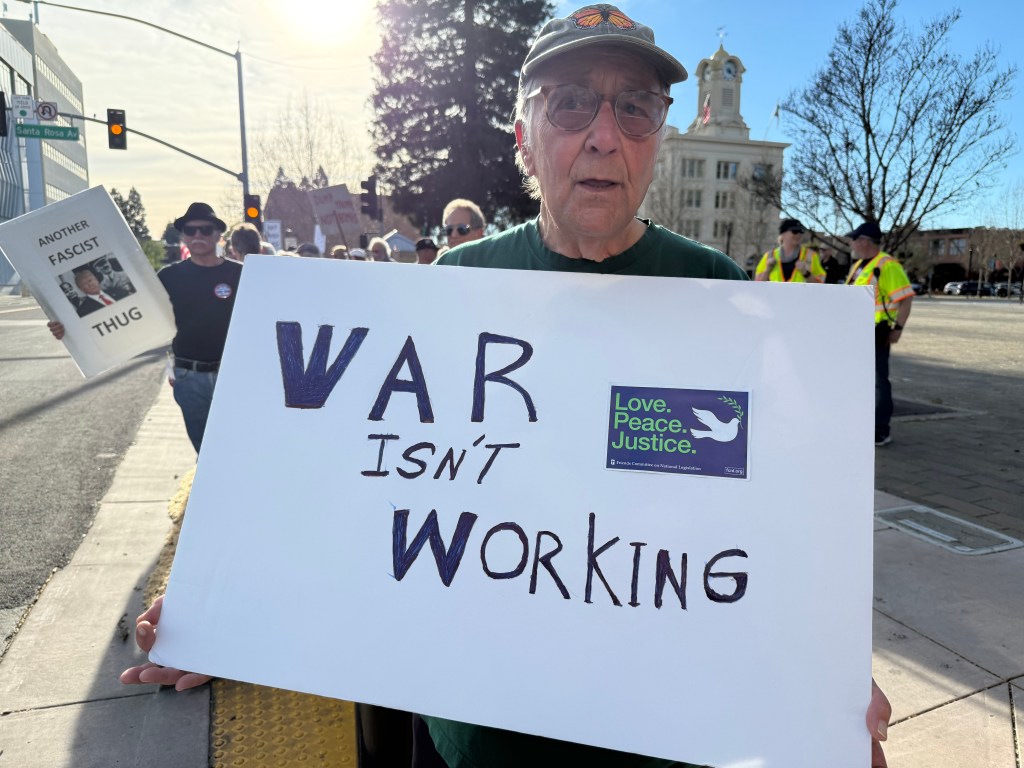

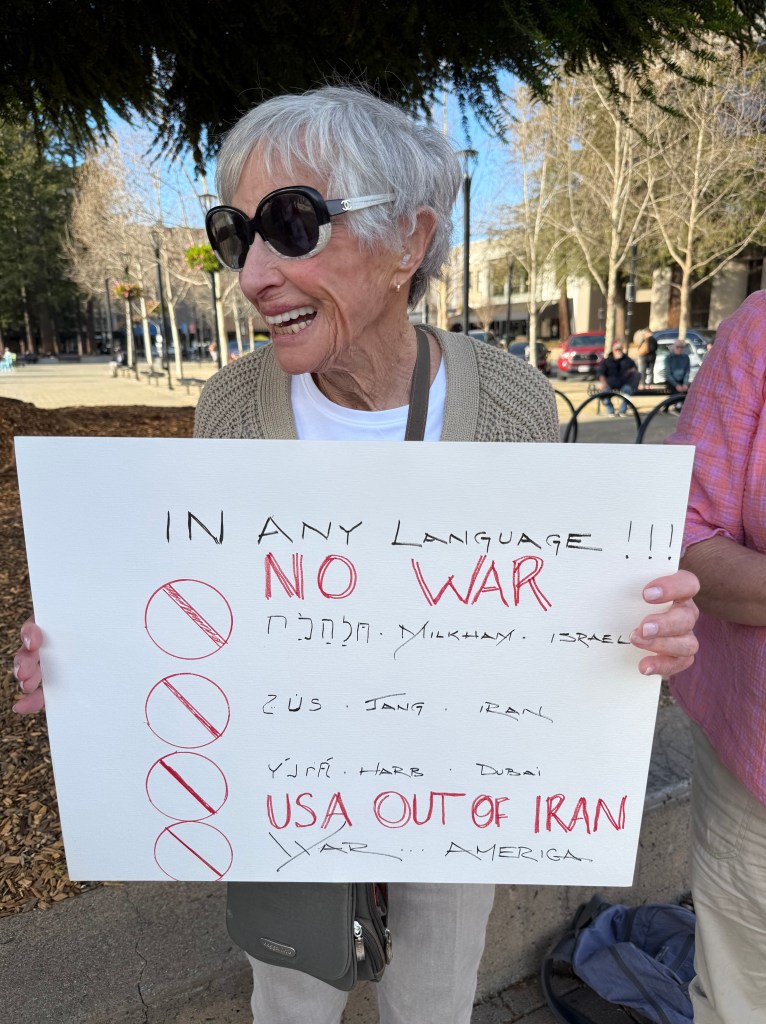

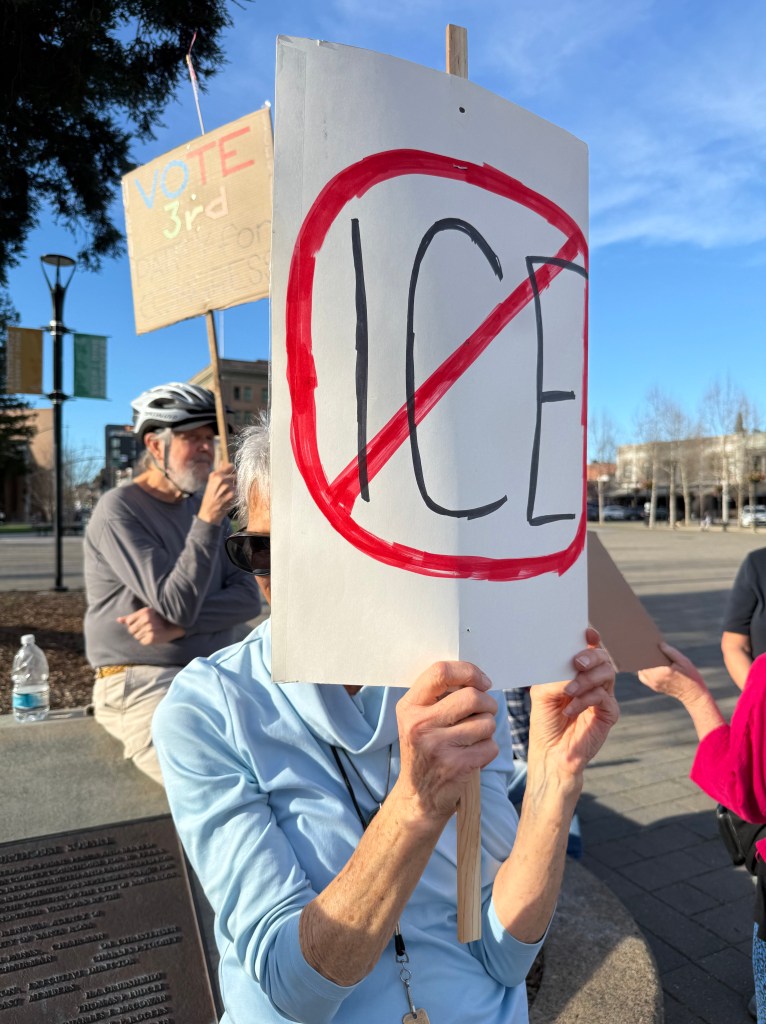

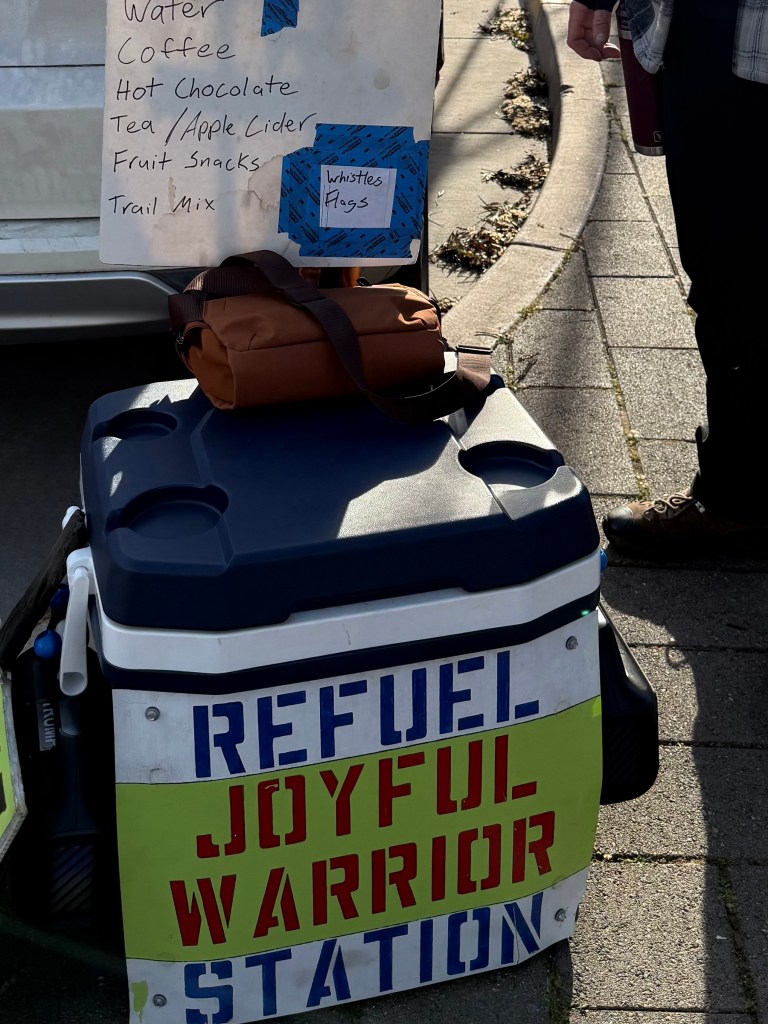

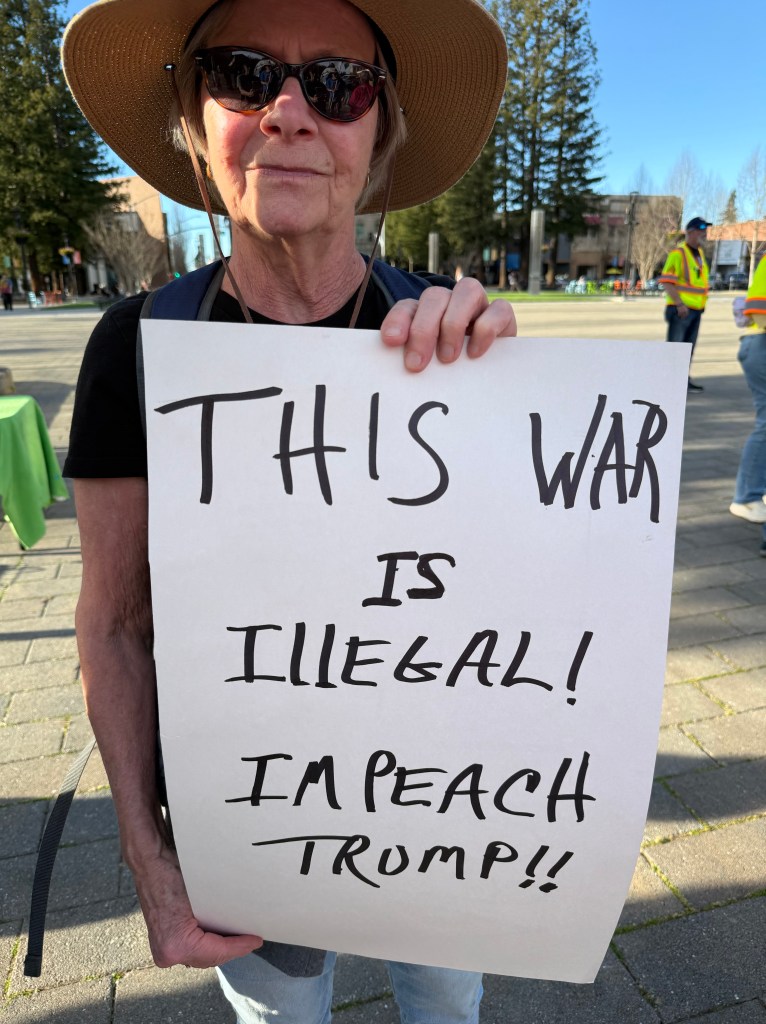

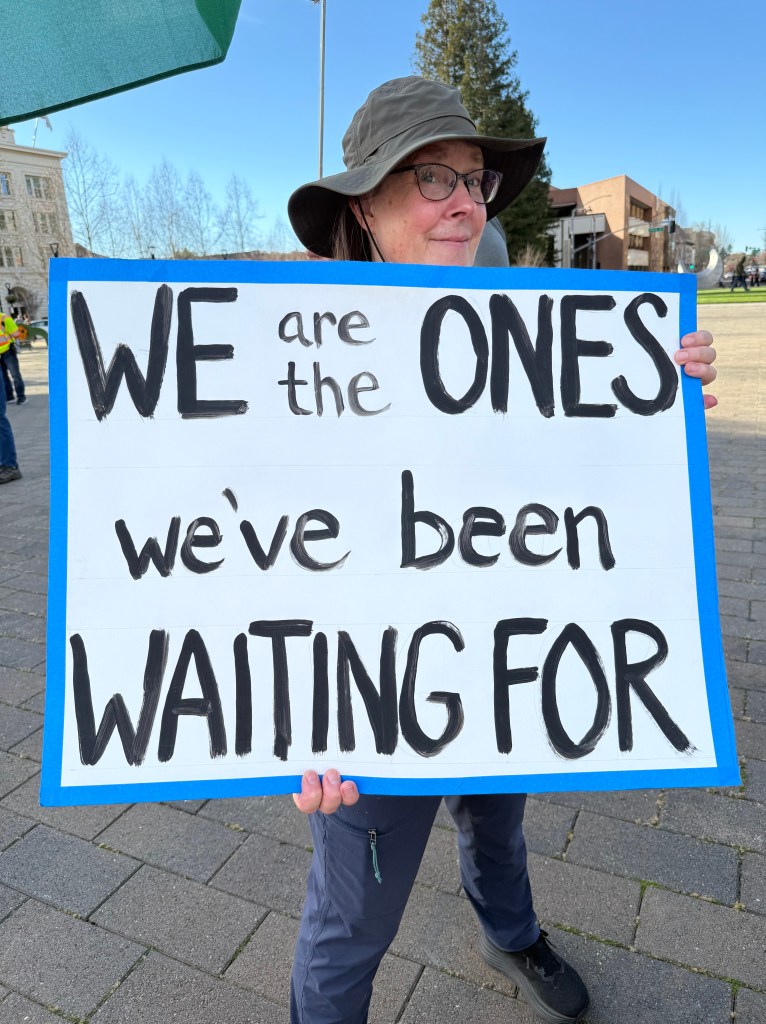

Some of the signs from our protests

Here in Sonoma County, protests are a near-daily occurrence. Demonstrators are targeting a wide range of issues: U.S. complicity in the genocide of Palestinians, Avelo Airline’s role in deportation flights, Elon Musk’s attacks on federal institutions like Social Security and Medicare/Medicaid, the gutting of the Veterans Administration, the criminalization of immigrants, assaults on free speech, and—by us tradeswomen—the dismantling of affirmative action and DEI initiatives.

The Palestinian community and its allies have been gathering every Sunday at the Santa Rosa town square since October 2023.

Weekly actions include:

In Sonoma Plaza, there’s a weekly vigil to resist Trump. Sebastopol hosts a Gaza solidarity vigil, along with Sitting for Survival, an environmental justice action.

Beyond the regular schedule, spontaneous and planned actions continue:

Trump’s goons are jailing citizens, and fear runs deep, especially among the undocumented and documented Latinx population—who make up roughly a third of Santa Rosa. But fear hasn’t silenced them. They continue to show up and speak out.

I’ve joined the North Bay Rapid Response Network, which mobilizes to defend our immigrant neighbors from ICE raids.

Meanwhile, our school systems are in crisis. Sonoma State University is slashing classes and programs in the name of austerity. Students and faculty are fighting back with protests, including a Gaza sit-in that nearly resulted in a breakthrough agreement with the administration.

Between all this, Holly and I made it to the Santa Rosa Rose Parade. The high school bands looked and sounded great—spirited and proud. Then, our Gay Day here on May 31, while clouded by conflict about participation by cops, still celebrated us queers.

And soon, I’ll hit the road heading to Yellowstone with a friend. On June 14, we’ll join protesting park rangers in Jackson, Wyoming as part of the No Kings! national day of action—a protest coordinated by Indivisible and partners taking place in hundreds of cities across the country.

On the Solstice, June 20 in the Northern Hemisphere, we expect to be in Winnemucca, Nevada, on the way home.

Happy Solstice to all—Winter and Summer!

Photo of the Pleiades: Digitized Sky Survey

Neighbors Getting Ready for the Big Demonstration Saturday

World War Two, the defining feature of my parents’ generation, affected my generation too. Maybe more than we know.

The Sound of Nazis

I was 15 going on 16, a sophomore in high school. It was 1965 and the Sound of Music was opening at the Capitol Theater in downtown Yakima. My mother offered to drive me and three girlfriends to see it.

Did my mother already know the story of Maria Von Trapp? Probably she knew of the post-war memoir or the 1959 Rogers and Hammerstein stage musical (she subscribed to the New Yorker magazine after all.) But whenever she learned of the story she must have wanted to see it. She had worked as a Red Cross “donut girl” in Europe during the war, passing out donuts to the troops on the front lines in Italy, France and Germany. She had lost her fiancé to a German land mine just days before they were to be married. She had witnessed the liberation of Dachau.

My girlfriends and I didn’t know the story. We were just excited to see the movie.

What a treat! We lived on the west side of town, out amidst the orchards and ranches. Our high school sat in the middle of an apple orchard. So getting anywhere required a car, even though in those days the school bus did pick us up and drop us off daily, but only after an hour spent driving around in the sticks.

The town of Yakima, Washington didn’t yet have a mall and so people still got dressed up when they went downtown to go shopping or see a movie at the Capitol Theater. When it was built in 1920 it had been the biggest and most ornate theater in the Northwest with seats for 2000.

By 1965 girls and women were no longer required to wear dresses, hats and gloves downtown. At school we were required to wear skirts, but on Saturdays we could wear play clothes—pedal pushers (zippers on the back or side only) and penny loafers with ankle socks. My mother still wore housedresses, even to clean the house, but she put on a polyester pantsuit to go to the movies.

We were teenagers, no longer children—young women really. Ponytails had metamorphosed into sleek pageboys and flips, which required sleeping on huge hair curlers. I had just converted to the popular flip, like a pageboy but flipped up at the ends instead of under. Beehive hairdos were in. You achieved a fuller look by ratting the hair, then combing over until it looked smooth.

We looked at the Simplicity pattern catalog to see what the new styles would be; Simplicity was remarkably prescient about fashion. Then we would just sew it. A-line dresses were comfortable and exceedingly easy to sew. Paisley was big. Hip hugger bell bottoms were popular and I made myself a pair with bright flowers in pinks and yellows.

Music didn’t move me like it did some others. I didn’t like my mother’s opera records or any of the odd assortment of 78 rpm records in her collection. As for popular music I just went with the flow, collecting 45 rpm records and playing them on a tiny square record player. The Beatles were big and we danced to “Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me.” My favorite 45 was “Chains” sung by the Cookies, a three-member group of Black women.

my baby’s got me locked up in chains

and they ain’t the kind that you can see, yeah

I didn’t know then that it was written by Carole King and Gerry Goffin.

I was a bit of a skeptic even then, irritably literal and unimaginative. My friend Susie had gone to the Beatles concert in San Francisco the year before and told me she couldn’t stop screaming while the group was singing. I asked her why girls do that. She couldn’t explain it; she said you just felt like it. I tried hard to understand but I really didn’t get it. Why would anyone scream while listening to music?

However, we were singers. We had formed a group called The Nonettes in eighth grade (there were nine of us). We sang Hootenanny songs like “500 Miles” and popular songs like “Winter Wonderland.” We hadn’t yet heard the Rodgers and Hammerstein music from the Sound of Music but we would learn it, since we were buying the Hi-Fi 33 rpm album after the show.

I was drawn into the musical immediately. What teenage girl would not identify with Maria—too exuberant to be a nun, too in love with the natural world to be ladylike. Did my girlfriends and I see ourselves as a problem to be solved?

The captain was like everyone’s father—militaristic, distant, full of orders, strict. But it was hard not to like the nuns even if they did kick Maria out of the convent.

We knew that booing at the movies was rude behavior, but we all booed silently when the baron’s lady friend and the children’s stepmother-to-be appeared. She would make a terrible mother to those children! Maria was so much better.

When the Nazis came on screen I heard what sounded like a low murmur coming from my mother. “Krauts,” she growled under her breath.

Then during the scene where the family is hiding from the ersatz boyfriend, she snarled, “Bastard.”

I felt myself flush. Talking in the movie theater was strictly forbidden and everyone sitting near us could hear my mother. They were turning around to shush her. Had my mother set out to embarrass me in front of my girlfriends?

I turned to frown at her. She sat on the edge of her seat with a death grip on the arm rests, her face twisted in anger. It was only then—20 years after the end of the war—that I began to see the depth of trauma my mother and many of our parents had experienced. Joan’s father, a bomber pilot, lost his mind. Rachel’s parents, having survived a concentration camp, could not talk about the war. My father and others viewed parenting as an extension of basic training.

It would take many more years to understand how my girlfriends and I—the next generation—were also deeply affected by the war that ended before we were born. #

“We are all at fault for allowing it to happen“

My mother wasn’t able to talk about the Nazis’ crimes against humanity until the program QB VII came on TV in 1974. Then she wrote this letter to the editor.

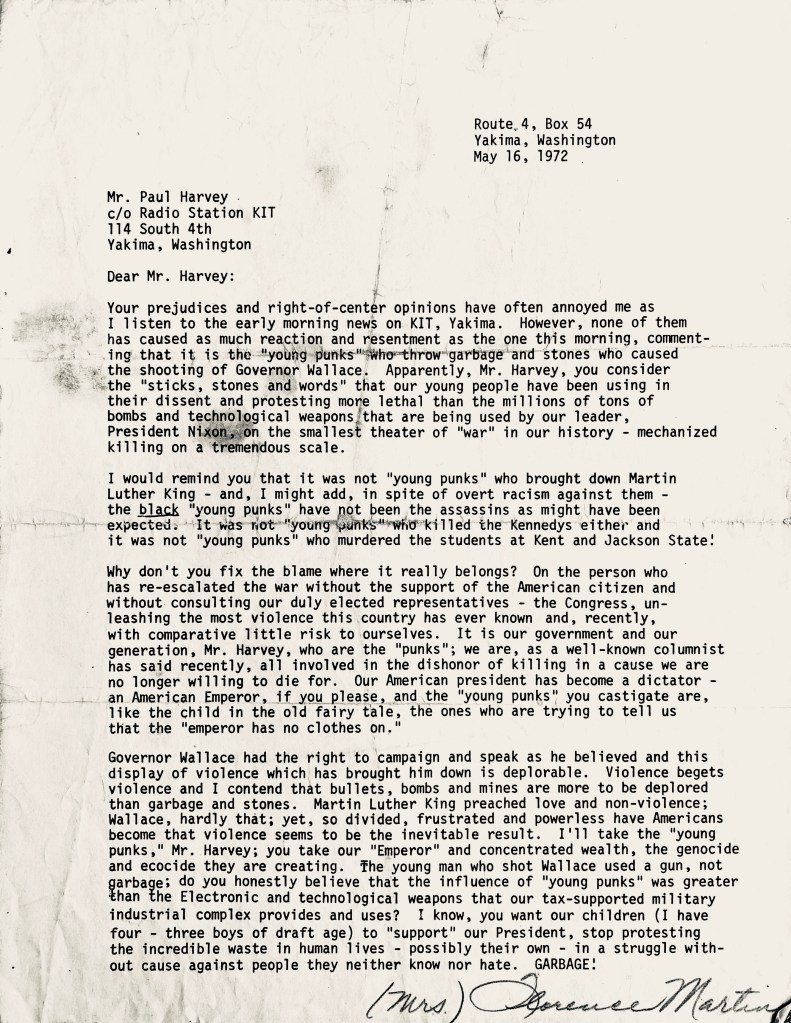

I contend that bullets, bombs and mines are more to be deplored than garbage and stones (thrown by dissenters).

Paul Harvey pissed us off for half a century. During my childhood the right-wing commentator was on the radio twice a day on weekdays and at noon on Saturdays railing against welfare cheats and championing American individualism. A close friend of Sen Joe McCarthy, the Rev Billy Graham and J. Edgar Hoover, he supported Cold War campaigns against communists and opposed social programs as socialist. Advertisers loved Harvey as he could make any ad sound like news. Salon Magazine called him the “finest huckster ever to roam the airwaves.”

Millions of Americans who, like us, got their news and information from the radio, were subjected to his diatribes. Beginning in 1952, Harvey kept talking right up till his death at 90 in 2009. He always left us fuming.

My mother got so mad at his attack on war protesters that she engaged her superpower—she wrote a letter.